The Central American Migrant Crisis Tests the Limits of Mexico’s Humanitarian System

The Brief

Rather than moving through Mexico to seek protection in the United States, Mexican government data shows that a growing number of individuals from countries such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Venezuela have applied and received humanitarian protections in Mexico.

Since 2014, the United States has seen a significant increase in the number of families and unaccompanied children who have sought protection in the country from violence in Central America. While this trend has tested the limits of the U.S. immigration system’s humanitarian and enforcement components in forms like the Central American migrant caravans, it has also presented challenges for Mexican authorities over the last year.

Rather than moving through Mexico to seek protection in the United States, Mexican government data shows that a growing number of individuals from countries such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Venezuela have applied and received humanitarian protections in Mexico. As Mexico has shifted from a transit to a receiving country of migrants, the new influx of refugees has pushed the limits of Mexico’s humanitarian immigration system, requiring attention from Mexican, international, and U.S. authorities to stave off scenarios where the system’s fragility results in more individuals coming to the U.S.-Mexico border.

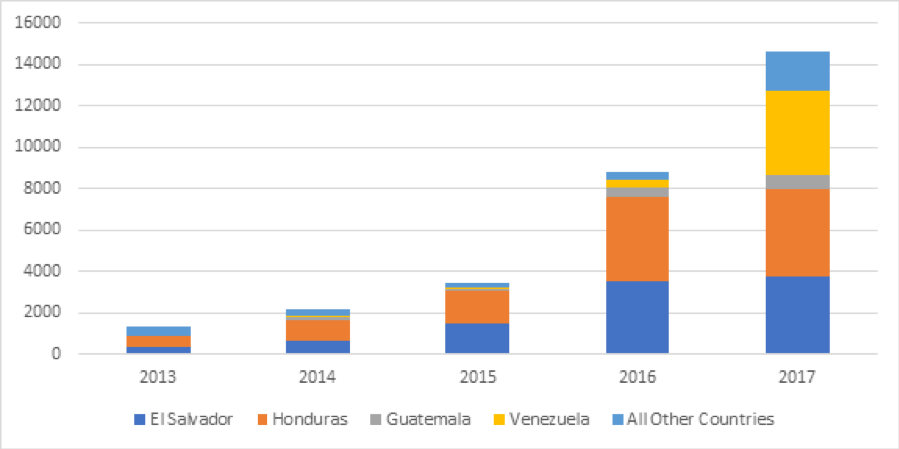

A review of data from the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), Mexico’s refugee agency, finds that a large number of individuals have filed refugee claims in Mexico since 2015, especially from Central American countries. As Figure 1 shows, the number of applications grew by over 1,000 percent between 2013 and 2017 as more individuals from El Salvador and Honduras submitted claims for these protections in Mexico. The increase in applications also coincided with a growing number of Venezuelans who sought protection in Mexico due to the country’s political and economic crisis that has driven its citizens to flee to other Latin American countries.

Figure 1: Number of Refugee Applications Filed in Mexico (2013?2017)

The increase in the number of refugee requests has corresponded with dramatic increases in the number of humanitarian protections granted and growth in the size of the application backlog. The number of refugee requests granted increased by 581 percent between 2013 and 2017. As Figure 2 shows, the number of individuals who abandoned their cases also increased between 2015 and 2017, which could suggest that individuals remained undocumented in Mexico, returned to their home countries, or moved to the United States after initially trying to seek asylum in the country.

More individuals have also received “complementary protection” status, a separate type of humanitarian protection that the Mexican government grants to individuals who are not considered refugees but who face the threat of death, torture, ill treatment, or other types of cruel inhumane treatment in their countries. As Figure 2 shows, the number of individuals receiving this form of humanitarian protection grew by 2,682 percent between 2013 and 2017. However, the increase in the number of refugee requests has generated a backlog of refugee cases: the number of cases pending in review grew by 6,671 percent between 2016 and 2017.

Figure 2: Outcomes of Refugee Requests Filed in Mexico (2013?2017)

The COMAR data shows that most grants of refugee status by Mexico were to Hondurans, Salvadorans, and Venezuelans. As Figure 3 shows, the number of individuals from Honduras and El Salvador who received refugee status peaked in 2016 when 1,254 Hondurans and 1,412 Salvadorans gained this status. In 2017, Venezuelans emerged as the largest group of individuals who received refugee status, with 907 individuals gaining this protection that year. Given that the Mexican government has not published the final figures for 2017 and 2018, it is likely that the number of Venezuelan refugees may increase.

Figure 3: Nationalities that Have Received Refugee Status in Mexico (2013?2017)

In the case of complementary protections, Hondurans and Salvadorans are the largest group of individuals who have received this type of humanitarian designation. As Figure 4 shows, these two groups received the greatest number of complementary protection designations in 2017, a year after refugee designations for this group peaked in 2016. This group has also driven the overall increase in the number of complementary protections that the Mexican government has granted to individuals seeking protection in the country. The Mexican government has not granted many complementary protections to Venezuelans; only 14 individuals received this protection between 2015 and 2016. More Venezuelans have received refugee status.

Figure 4: Nationalities That Have Received Complementary Protection Status in Mexico (2013?2017)

Finally, the Mexican government has issued an increasing number of humanitarian-based visas, albeit at much lower levels than refugee and complementary protection designation rates. As Figure 5 shows, the number of individuals who received a “visitor for humanitarian reasons” visa increased from 623 in 2015 to 9,642 in 2017. The Mexican government introduced this visa in 2012 to allow victims of crime and unaccompanied children to live and work in Mexico for a year-long period, which they can continuously renew every year.

Figure 5: Number of “Visitor for Humanitarian Reasons” Visas Issued (2013?2017)

This data has two major implications for U.S. foreign and immigration policy. First, Mexico has clearly shifted from serving as a transit country for Central American migrants seeking humanitarian protection in the United States to one that grants these populations humanitarian protections in its own territory. While Mexico has shed its status as a primary source of migrants to the United States, this latest transition is more challenging since it places greater burdens on the country’s humanitarian protection system. As some reports have noted, COMAR lacks the staffing and resources to work through its current refugee case backlog, meaning that migrants will have to wait longer to learn whether they will receive protection. Given that the conditions in the Northern Triangle and Venezuela will continue to drive individuals to leave these countries, the increasing levels of refugees could push Mexico’s fragile humanitarian system to the brink of collapse?and send more migrants to the U.S.-Mexico border.

The challenges facing COMAR also point to a broader issue regarding the capacity of institutions in the United States, Mexico, and Central America to effectively manage migrant flows in the region. The United States should have a vested interest in improving the capacity and integrity of immigration institutions in Mexico, as well as its own immigration system, to effectively and efficiently manage this new migration flow. The United States and Mexico also must work with their Central American partners to ensure that these countries have political and administrative institutions that can effectively govern, including developing and implementing security programs to combat the rampant crime and violence. Additionally, longer term investments are needed in the development of strong, job-creating economies that can provide opportunities outside of gangs to the disproportionate number of young people of prime migration age to reduce push factors. While these measures may not generate immediate effects at the U.S.-Mexico border, they will ensure that the region has strong institutions that can withstand these dramatic migratory shifts and strengthen the integrity of the U.S. immigration system and the nation’s borders.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.