Crisis at the Border? Overall Numbers Down, but New Migrant Flows Are Testing the System

The Brief

This data highlights how sudden changes in migrant flows can present new challenges to the U.S. immigration system. In contrast to prior generations of migrant flows at the U.S.-Mexico border, which consisted overwhelmingly of single Mexican or Central American economic migrants (mostly male) who could be quickly deported from the United States, many of the latest arrivals are families seeking humanitarian protection from the violence in Central America.

In 2018, the increase in family apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border from the previous year led the Trump administration to call for and adopt stricter enforcement policies to fight what they believe is a crisis at the border. A review of government apprehensions data provides a more nuanced picture: while overall Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 apprehensions do not support the administration’s claims that a mass influx of individuals are coming across the U.S.-Mexico border, apprehensions of families with asylum claims (e.g., individuals seeking protection in the United States from prosecution in their home country) have increased over the last three years, presenting new challenges for U.S. border officials accustomed to managing primarily adult economic immigration from Mexico and Central America.

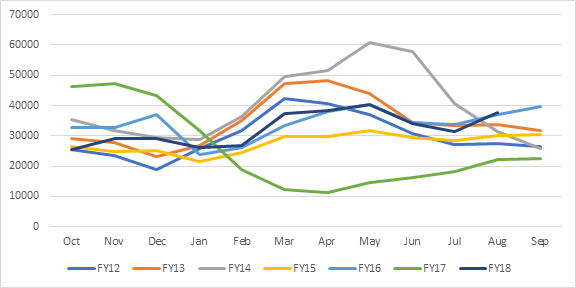

Southwest border apprehensions increased in FY2018 after hitting historic lows during most of FY2017. As Figure 1 shows, apprehensions decreased from 47,211 in November 2016 to a historic low of 11,127 in April 2017, a drop from elevated levels in the immediately preceding months, in which immigrants rushed to enter the United States before President Trump’s inauguration in January 2017. After April 2017, however, the declines reversed, and increased through FY2018, showing that President Trump’s efforts to use tough immigration rhetoric to deter undocumented immigrants from crossing the U.S.-Mexico border didn’t meet these goals after his first year in office.

Figure 1: Southwest Border Apprehensions (FY2012-FY2018)

FY2018’s apprehension figures align with seasonal apprehension patterns. As Figure 1 shows, FY2012, FY2016, and FY2018 had similar levels of apprehensions, which were lower than FY2014 and higher than FY2017. FY2018’s apprehension data has a similar trajectory to those of FY2012, FY2013, FY2015, and FY2016, which followed seasonal patterns in which more immigrants crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in the spring and fall. In short, FY2018 shows a return to form for overall apprehension levels rather than marking the start of a broad “crisis” at the U.S.-Mexico border.

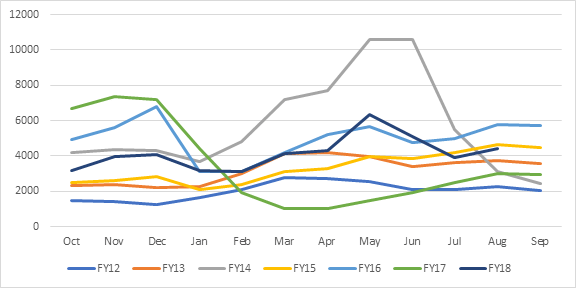

FY2018 apprehension data for unaccompanied children (UACs) also exhibited similar trends. As Figure 2 shows, FY2014 had the highest levels of UAC apprehensions, which reflects the large influx of UACs who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in summer 2014. However, these levels decreased significantly in FY2017, along with overall apprehensions, dropping from 7,346 apprehensions in November 2017 to 4,141 apprehensions in March 2017. However, UAC apprehensions in FY2018 returned to the apprehension levels and seasonal trajectories seen in FY2012 to FY2013 as well as FY2015 to FY2016, making it another case where border apprehensions reverted to pre-FY2017 levels.

Figure 2: Southwest Border Unaccompanied Minor Apprehensions (FY2012-FY2018)

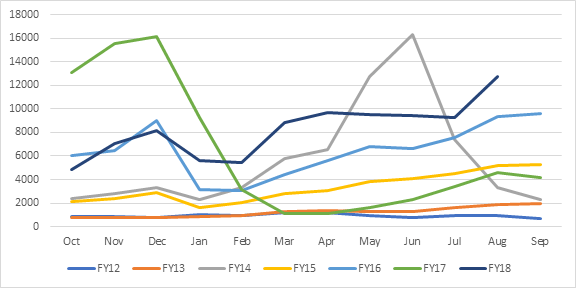

Family unit apprehensions (in other words, individuals who are apprehended as part of a family) have increased significantly over the last year, however. As Figure 3 shows, family unit apprehensions hit the highest peak in June 2014, when CBP detained 16,330 individuals, many of whom were part of the 2014 surge of migrants fleeing violence in Central America. After family unit apprehensions hit the second largest peak in December 2016, 16,139 apprehensions, FY2017 apprehensions dropped to FY2012 and FY2013 levels, which are historically low for this group. However, family unit apprehensions increased significantly in FY2018, superseding the levels seen in FY2015, FY2016, and parts of FY2014.

Figure 3: Southwest Border Family Unit Apprehensions (FY2012-FY2018)

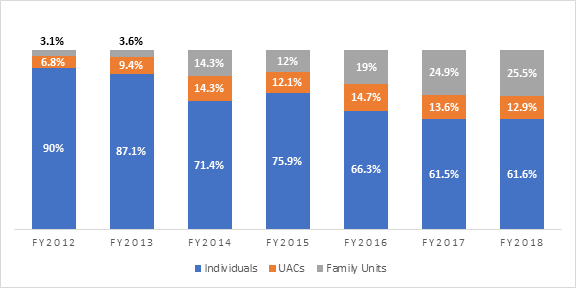

Family apprehensions have also become a greater percentage of total apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border. As Figure 4 shows, UAC apprehensions have fluctuated between 12.1 percent and 14.7 percent of all southwest border apprehensions. In contrast, family unit apprehensions have increased from 3.1 percent of total southwest border apprehensions in FY2012 to 25.5 percent in FY2018, suggesting that families fleeing from Central America have changed the composition of the individuals entering the country illegally over the last three years.

Figure 4: Breakdown of Different Categories of Southwest Border Apprehensions (FY2012-FY2018)

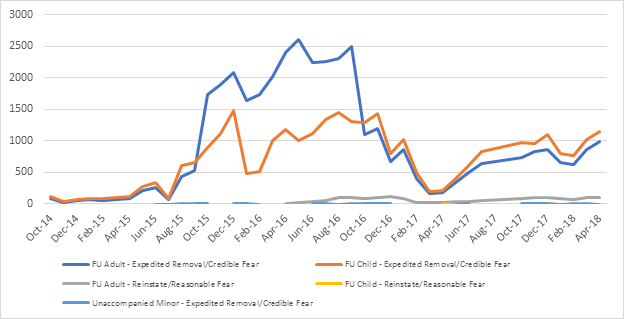

CBP apprehension data also shows more individuals in the family unit apprehensions category are making asylum claims. As Figure 5 shows, the number of individuals in the expedited removal process who made credible fear requests (e.g., individuals who expressed fear of returning to their home country to begin the asylum process), or reasonable fear requests (e.g., individuals who expressed fear of returning home during the reinstatement of a prior removal order to begin the asylum process), grew between October 2015 and October 2016, which covered the first wave of Central American migrants fleeing violence in the region and the rush of individuals who entered the United States before President Trump’s inauguration. After dropping significantly in 2017, these numbers rebounded through April 2018, suggesting that U.S. border officials are processing a much larger caseload of asylum cases for adults and children apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border than they were in FY2017[note]This data also suggests that the composition of family units making asylum claims in expedited removal proceedings has changed over time. As the chart shows, more children in family units have been making credible fear claims in expedited removal proceedings than adults in family units since June 2017, which may indicate that the ratio of children to adults in family groups seeking asylum protections has grown over the last year. In contrast, more family unit adults made credible fear claims than family unit children in the October 2016 to October 2017 spike, indicating that earlier arrivals of individuals making asylum claims consisted of adults traveling with fewer children to the United States.[/note].

Figure 5: Border Patrol Humanitarian Disposition for Family Unit and Unaccompanied Minor Apprehensions (FY2015-FY2018)1

Source: TRAC

This data highlights how sudden changes in migrant flows can present new challenges to the U.S. immigration system. In contrast to prior generations of migrant flows at the U.S.-Mexico border, which consisted overwhelmingly of single Mexican or Central American economic migrants (mostly male) who could be quickly deported from the United States, many of the latest arrivals are families seeking humanitarian protection from the violence in Central America. To address this, U.S. officials must invest more resources into reviewing cases against individuals in removal proceedings, which can include examining complex asylum claims for adults and their children. Given that the immigration system lacks the structures and resources to adjust to sudden shifts in migrant flows stemming from non-economic factors like violence, crime, and other driving factors, the influx of these cases will continue to push the system’s limits.

1These figures come from U.S. Customs and Border Protection data obtained by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) through Freedom of Information Act requests. The data is current as of September 2018 and does not include figures for August and September 2017. Additional information on this data is available at http://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/cbparrest/about_data.html.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.