Record Number of Cases in Immigration Courts is Simmering Crisis

As of August 2017, there are 632,261 pending immigration court cases in the United States, a staggering record high. While illegal crossings at the southwest border have precipitously dropped overall since January, despite ticking back up slightly in the summer months, the downturn in apprehensions is not enough to slow the ever-increasing number of unheard cases in the immigration courts. There are a variety of other factors contributing to this overwhelming number, many of which are not part of the current immigration debate.

A Snapshot of Immigration Court Trends

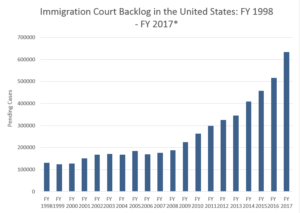

The total number of pending cases in immigration courts nationwide has been on a steady uptick since 2006. However, the increase in backlogged cases from fiscal year (FY) 2016 to FY 2017 is over 115,000 cases, much higher than the increase from FY 2015 to 2016, which was about 60,000 cases.

Source: TRAC *FY 2017 represents available data from September 2016-August 2017, one month short of the fiscal year.

Due to the ballooning number of court cases, wait times to receive a trial in immigration court have also increased. Immigrants who are called to appear before a judge have to wait an average of 682 days for their case to be heard. This figure is the nationwide average; in Colorado, the wait time is 1,042 days, or almost three years, to see an immigration judge.

Causes of the Current Backlog

The rapid uptick in cases referred to immigration court began in 2014, which marked the beginning of a dramatic increase in border crossings by children and families from Central America. In FY 2014, nearly 86,000 unaccompanied children (UACs) and family units from Central America were apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border, shattering previous records. These numbers slacked off in 2015, dropping to 43,600, but they surged back in 2016 with 117,300 UACs and family unit members apprehended. According to the most recent available data from CBP, there were 109,940 UACs and family unit members apprehended in FY 2017 thus far (October 2016-August 2017). This number would include the surge of Central Americans crossing the border that occurred between President Trump’s election and inauguration, as many tried to cross before incoming President Trump’s promised immigration crackdown. The numbers from these last four years alone have completely subsumed U.S. immigration courts.

Both immigrant advocates and enforcement hawks agree that the backlog status quo is unacceptable, but tackling it is far from simple.

In addition to the previous administration’s trouble with Central American border crossers, the backlog has been unintentionally affected by new enforcement guidelines. President Trump’s removal priorities are much broader than those of former President Barack Obama. For example, a February 2017 Department of Homeland Security memo ended Obama-era prosecutorial discretion, the decision by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) attorneys to drop charges against certain otherwise law-abiding undocumented immigrants to focus on violent criminals. A separate February 2017 memo issued by the Enforcement and Removal Operations Division of ICE expanded on the earlier DHS memo by instructing its officers that they “will take enforcement action against all removable aliens encountered in the course of their duties.” According to statistics published by ICE, between January and April of 2017, arrest of undocumented immigrants increased 40 percent over the same time period in 2016 from 30,028 individuals to 41,318. This statistic includes an 18.2 percent increase in arrests of undocumented immigrants who are also convicted criminals.

As a result of these policies, the pool of undocumented immigrants who end up in the immigration court system has grown exponentially larger in a very short amount of time. As these new enforcement actions play out, and are sent before immigration judges, hundreds of thousands of new cases could be added to the backlog. In fact, fewer immigrants are being deported now than under the previous administration, despite the fact that arrests have increased, largely due to the court backlog.

Tackling the Backlog

Both immigrant advocates and enforcement hawks agree that the backlog status quo is unacceptable, but tackling it is far from simple. The administration has increased the use of expedited removal processes, procedures that do not require appearing in immigration court, which had already been increased under President Obama, and expanded the eligibility criteria for expedited removal. Advocates argue that this removes the already-limited due process granted to immigrants, but also risks returning some individuals to situations that could be dangerous to them.

Additionally, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the addition of 125 immigration judges over two years, with 50 in 2017 and 75 in 2018. However, a former immigration judge quoted in the Atlantic estimated that, “125 new judges could do fewer than 100,000 cases a year once they’re up and trained.” If that estimate is accurate, it would take five to six years for those 125 new judges to reduce the backlog.

The administration has also made efforts to redeploy immigration judges from other areas of the country to help the backlog at the southwest border. While this is certainly the area in which the majority of cases need to be heard, the effort has actually extended the backlog in the areas the judges are coming from. For example, as of July of this year, half of New York City’s 30 immigration judges had been reassigned to cases at the border, resulting in delays on top of an existing backlog of 80,000 cases in the city’s immigration court.

Most recently, the Justice Department released a memo on July 31, 2017, that asked immigration judges to issue fewer continuances, which are a routine delay in the court proceedings that give the litigants additional time to prepare for their cases. As noted in the memo, “the delays caused by granting multiple and lengthy continuances, when multiplied across the entire immigration court system, exacerbate already crowded immigration dockets.” The memo asks that immigration judges not routinely or automatically grant continuances unless the plaintiffs can “show good cause or a clear case law basis.” The memo also reminds immigration judges that the Immigration and Nationality Act does not establish continuances as a right in these proceedings. Immigration attorneys and advocates argue that eliminated continuances will mean that many of them will not even be able to get the case files for their clients from DHS, which can take weeks through a Freedom of Information Act request.

As the Trump administration continues to focus on increasing arrests of unauthorized immigrants, the near-term will only see the immigration court backlog grow. While the administration has made initial efforts to address this backlog, it is unclear what steps might be necessary ensure speedy but fair hearings for immigrants facing deportation. It is clear, however, that making a significant and lasting dent in immigration court backlog will require a massive undertaking.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.