The Kurds, Sykes-Picot and Quest for Redrawing Borders

Kurdish Regional Government leader Mesut Barzani recently announced that, with the hundredth anniversary of the Sykes-Picot treaty fast approaching, “[world leaders] have come to this conclusion that the era of Sykes-Picot is over.” For Barzani, the implication was obvious: it was time to redraw the region’s outdated, arbitrary, European imposed borders and create an independent Kurdish state.

It’s easy to see why Kurds in particular would resent the borders that emerged from the defeat of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. But a closer look at the historical origins of these lines reveals that the Kurds did not lose out through bad luck or arbitrary imperial fiat. Rather this history shows some of the embedded challenges that faced Kurdish nationalists a century ago, and sheds light on the factors influencing regional politics today.

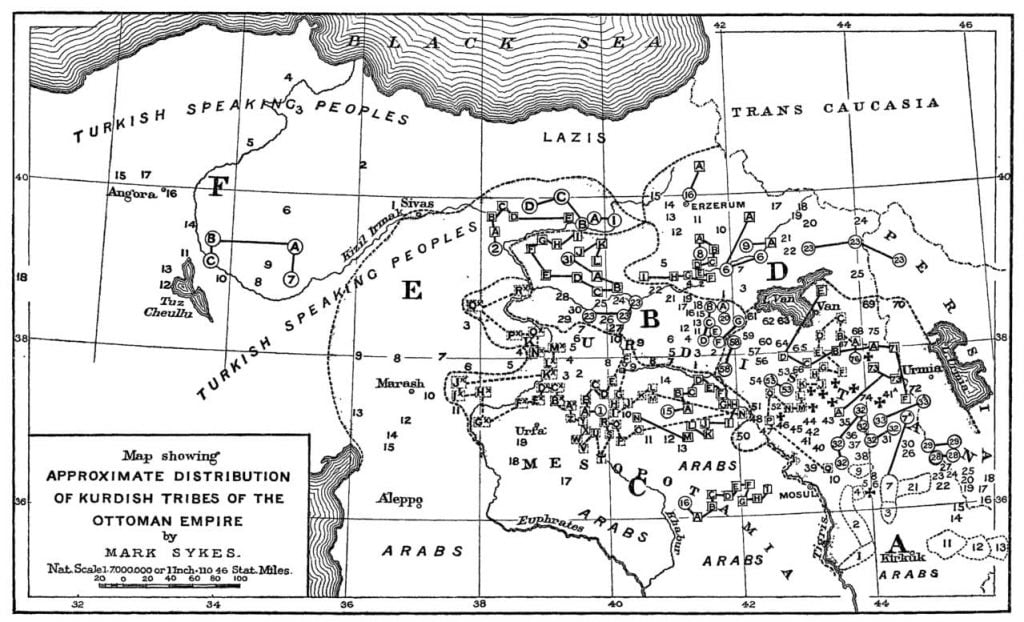

Mark Sykes was, by late British imperial standards, something of a Kurdish specialist. He even published an ethnographic paper on the Kurds, drawing on “the results of about 7,500 miles of riding and innumerable conversations with policemen, muleteers, mullahs, chieftains, sheep drovers [and] horse dealers” in the region. As with many imperial officials, though, local knowledge did not necessarily produce an abiding respect for locals, and, as his remarkably confusing map suggests, Sykes came away from his travels in Kurdistan without much faith in the Kurds as a unified nation ready for self-government.

“The Kurdish Tribes of the Ottoman Empire” by Mark Sykes, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol. 38 (Jul. – Dec., 1908)

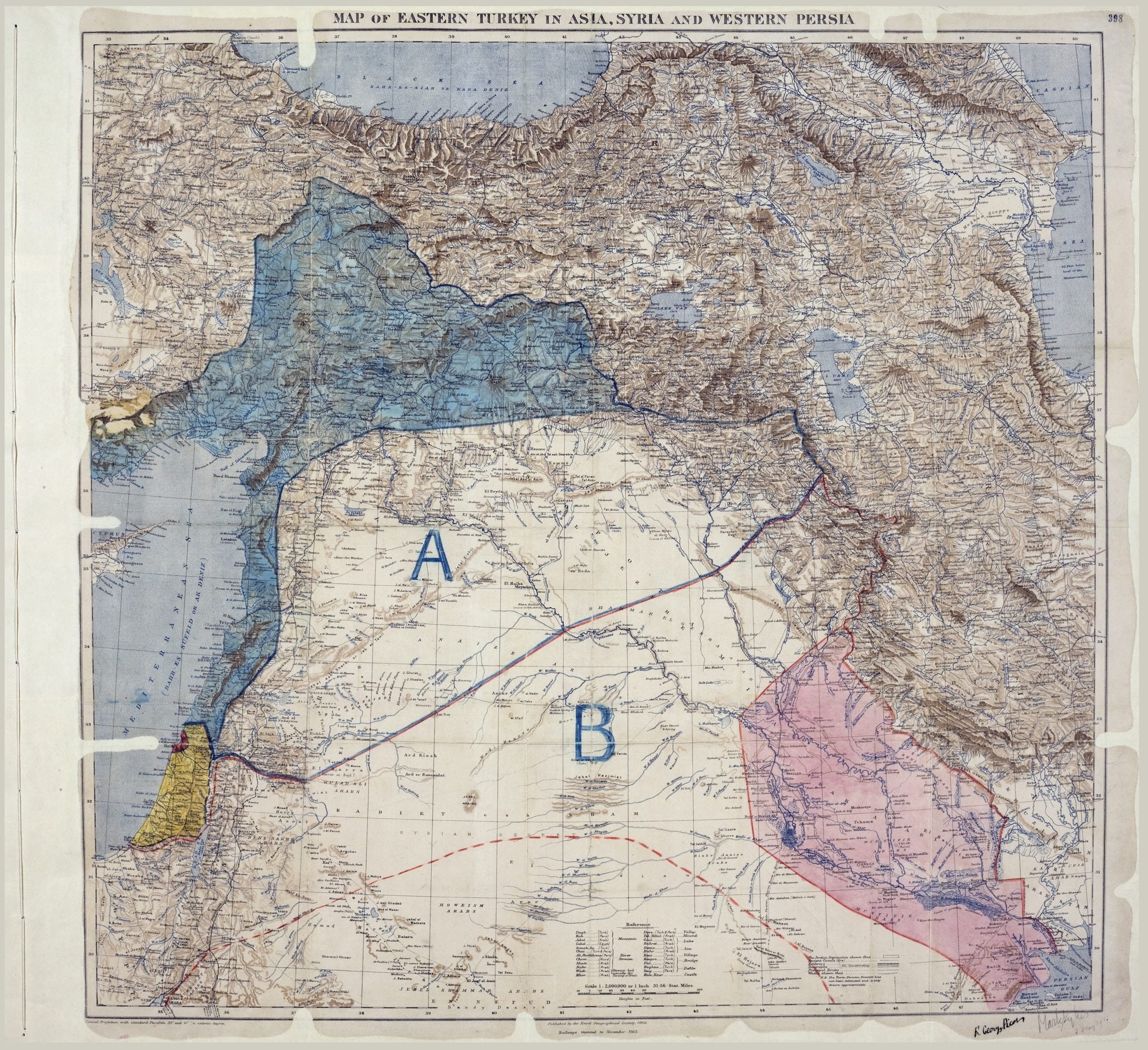

It is telling that the secret agreement Sykes inked with his French colleague François Georges-Picot divided up the Kurdish inhabited part of the Ottoman Empire, but did so in a completely different way than the current borders do. A quick look at the original Sykes-Picot map shows that in the original plan, many of the Kurdish inhabited areas now in Syria and Turkey would have ended up under French control, while the region east of Kirkuk would have ended up in British control and the most Southeastern region of what is now Turkey would have been included in a new Armenian state. (The status of Kurds living in Persia, meanwhile, would not have changed.)

Map of the Sykes?Picot agreement, which was signed by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot on May 8, 1916. (The National Archives/Wikimedia Commons)?

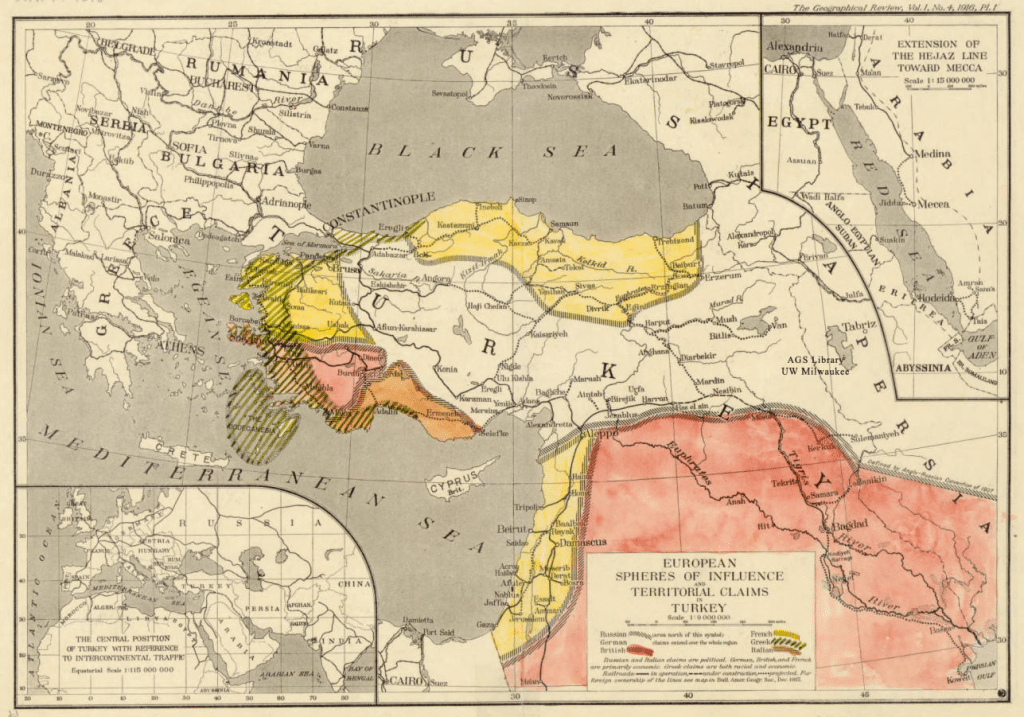

Perhaps the best evidence of how heavily stacked the deck was against Kurdish independence comes from the many other proposals for the regional borders floated at the time of Sykes-Picot, all of which in one way or another denied the Kurds an independent nation-state. Lawrence of Arabia’s preferred map, which many have since touted as the honest alternative to the Sykes-Picot agreement, simply designates the majority of Kurdish inhabited land with a series of question marks?while reserving other Kurdish regions for British Iraq, Armenia, and a British controlled Arab state. An American expert, speculating on the region’s future from afar in 1916, envisioned instead that the Kurds would soon be united under an expansive Russian sphere of influence.

“Europe at Turkey’s Door” by Leon Dominian Geographical Review, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Apr., 1916)

But ultimately even the Sykes-Picot plan was not realized, since facts on the ground got in the way. By the end of World War I, the British army had already seized Mosul (designated to the French) and, when they signed the treaty of Sevres with the seemingly defeated Ottoman Empire, laid claim to what is now the predominantly Kurdish part of Turkey as well. The British may have eventually planned to sponsor something along the lines of a Kurdish mandate in this region, but they never had the chance. Shortly after the end of the war, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk organized the remnants of the Ottoman army and, in the course of what is now called the Turkish War of Independence, re-conquered the territory of modern Turkey.

In a fight that appeared to pit the British and the Ottoman Empires against each other, the choice for Kurdish leaders at the time was largely one of which side to support. Some sought to establish contacts with the British and the international community in the hopes of somehow securing a semi-independent state. But many joined with Ataturk’s national movement to avoid being colonized by a European, Christian, or foreign power.

After the fighting was over, British-Turkish conflict continued in the form of a diplomatic dispute over control of Mosul. As explained by historian Sara Pursley, Kurds, like many other communities in Mosul, were divided over what political future seemed most promising. Some felt their territory would be better off in Turkey, some felt it would be better off in Iraq. And still others took up arms in support of independence. But, like Kurdish groups that rebelled against the Turkish state in the 1920s, their efforts were defeated, in this case by the brutal and effective use of British air power. Britain, in fact, used its efforts to defend Mosul against Turkey and Kurdish rebels alike in order to curry favor with Iraqi nationalists in Baghdad, many of whom resented the British occupation but realized they needed British help to preserve their control of the province.

For Kurds, as for many other groups after World War I, true independence was never an option. At best, some kind of British-sponsored semi-independence seemed to be on offer, which many people, understandably, were wary of. Today, in Turkey and Syria, those seeking greater Kurdish autonomy have at times faced a similar dilemma: whether to try to advance their aspirations for greater self-rule by cooperating with national governments that do not support their full independence.

In Turkey, for example, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) was, until recently, negotiating with the Justice and Development Party, in pursuit of a deal that would give Kurds more regional autonomy in the Southeast in return for supporting Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s increased power over the rest of the country through an enhanced presidential system. Then, when Kurdish politicians in the People’s Democratic Party subsequently rejected this arrangement, declaring in the spring of 2015 that they would not help make Erdogan president, it seemed to reflect their growing conviction that the limited degree of autonomy Erdogan was willing to offer them was not enough.

In Syria, meanwhile, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) has been successful in creating a Kurdish statelet called Rojava by establishing a modus vivendi with the Syrian President Bashar Assad regime. At times, most recently in their simultaneous attacks against rebels in the Azaz corridor, this has made the regime and the PYD appear to be allies. But if Kurdish interests currently converge with Assad’s in the midst of the country’s civil war, the degree of autonomy allotted to Rojava will certainly be contentious in any post-conflict situation.

Finally in Iraq, by contrast, Barzani and the KRG feel they are on the verge of independence. Turkey?the first country in the region to overturn proposed borders at the end of WWI?has voiced its disapproval. In fact, Turkish government spokesman Omer Celik made the somewhat confusing case that a new Kurdish state would “only lead to the further reinforcement of the artificial agenda that Sykes-Picot created.” In explaining the alternative, however, he was more persuasive, suggesting that instead of redrawing borders “what we need to consider in this region is how all ethnic groups and all sectarian groups can create new zones of prosperity that go beyond borders, while also respecting existing borders, new freedoms, new political approaches and new cultural integrations.”

The tragedy, of course, is that over the last six months the Turkish government has abandoned its commitment to new freedoms and cultural integrations in dealing with its own Kurdish population, opting for old and unsuccessful approaches instead. By living up to its own idealistic rhetoric, however, Turkey could still help to permanently put the political traumas of the past century to rest.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now