Do You Know How Much Your 401(k) Plan Costs Uncle Sam? (He Doesn’t!)

In 2014, the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) launched the Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings, led by former Senator Kent Conrad and WL Ross & Co. Vice Chairman Jim Lockhart. The commission will consider and make recommendations regarding Social Security, pensions, defined contribution (DC) savings vehicles, strategies to generate lifetime income and other factors that affect retirement security.

This BPC-staff authored post is the ninth in a series that will outline the state of retirement in America and provide a sense of the challenges that the commission seeks to address in its 2015 report.

For more information on the topics below and in the rest of this series, see our recently released staff paper, A Diversity of Risks: The Challenge of Retirement Preparedness in America.

The main reason that a 401(k) plan or an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) is a good place to save money for retirement is because the U.S. government offers tax benefits for doing so, both for traditional and Roth-style accounts. But despite the fact that the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) releases annual estimates of how much these incentives cost the federal government, we don’t really know how much they are worth. The reason? The system of “cash” scoring that JCT uses only accounts for funds spent and revenues collected over the next few years, but saving for retirement is a lifetime process. A different accounting method called “net-present-value” scoring may offer a better way to understand retirement tax benefits.

The Problem with Cash Scores

Most tax incentives that the government provides are one-time benefits: I can deduct the value of mortgage interest from my income this year without changing my taxable income next year. But the tax benefit for funds deposited in traditional or Roth retirement accounts is different because putting money in a retirement account does change my future taxable income, although often not until many years or even decades down the road, well outside of the traditional ten-year budget scoring window.1

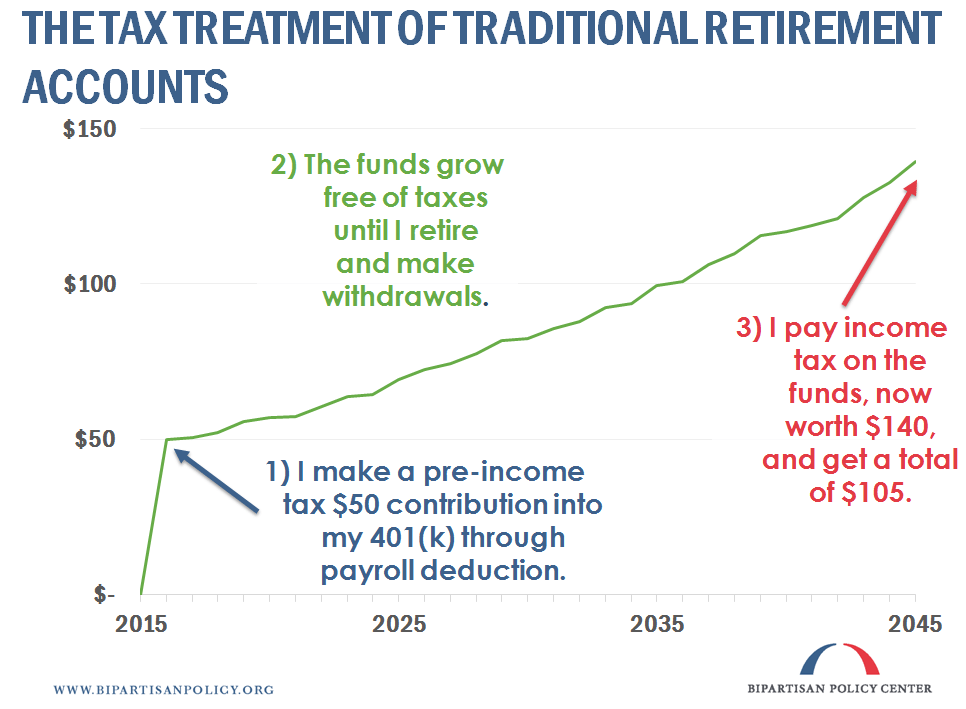

In the case of a traditional IRA or 401(k) plan, which are tax-deferred, any contributions made (within annual limits) reduce taxable income in that year.2 But not all of that foregone income-tax revenue is lost forever. While earnings within the accounts are not taxed right away, withdrawals from the accounts are taxed as ordinary income.3

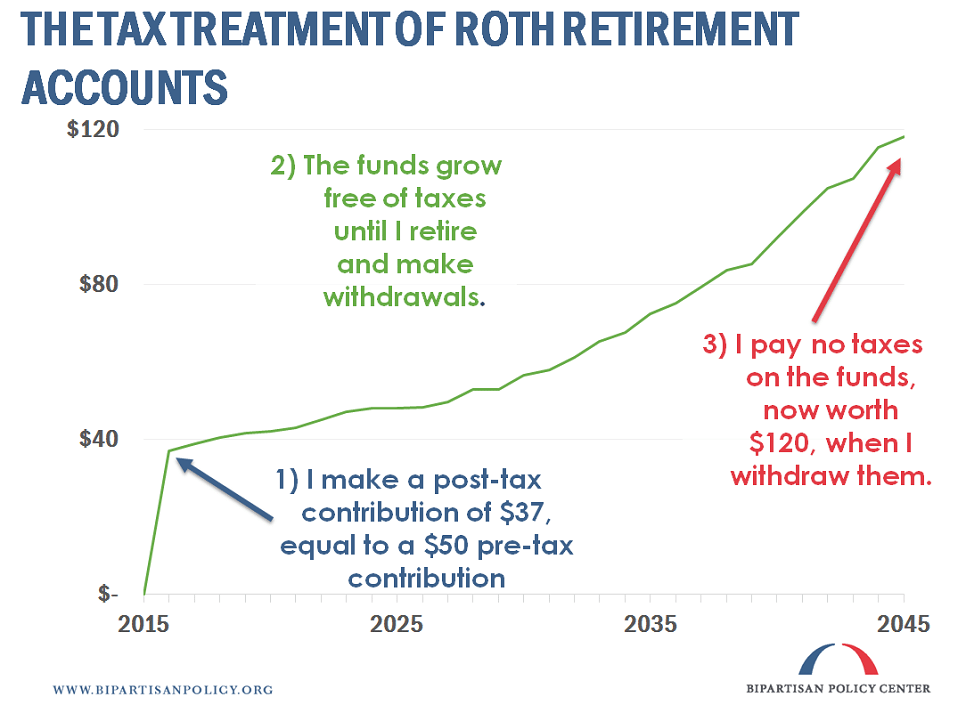

On the other hand, contributions to Roth IRAs or Roth 401(k) plans are made with after-tax dollars. Withdrawals by the participant are not taxed, so the growth of assets held in the account (i.e., the accumulation of earnings, including dividends, interest, and capital gains, over time), sometimes called “inside buildup,” is never taxed.

Under a five- or ten-year cash-based budget estimate, the cost to the federal budget of deferred taxation of a traditional retirement account looks deceptively large because it includes the entire current revenue loss from near-term contributions, but it ignores a significant portion of future revenue gains from withdrawals, much of which will occur more than five or ten years later. Conversely, today’s budget estimates understate the cost of Roth accounts, because the scoring ignores much of the cost of allowing tax-free withdrawals of the increased account assets many years in the future, well outside the ten-year scoring window.

Similar issues arise when the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the cost of proposed legislation that would expand access to and the use of tax-advantaged retirement savings vehicles. So what’s the solution?

Net Present Value Can Help

There’s no perfect answer, but a net-present-value (NPV) score would provide a much closer estimate of the true cost of current law retirement tax expenditures and of legislation that would affect the use of IRAs and 401(k) plans. An NPV score comes up with one number that reflects both the immediate fiscal cost (or benefit) of a policy today and the benefit (or cost) in the future. For a traditional retirement account with deferred taxation, that means combining the value of the lost taxes today with the projected taxes collected when withdrawals happen.

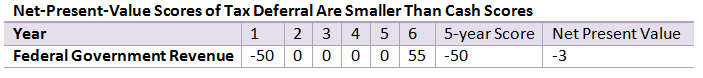

Here’s an example: Jennifer contributes to a tax-deferred account in Year 1 such that the government foregoes $50 in tax revenue. She then lets the money grow for six years, withdraws the entire amount, and pays $55 in taxes. Because the withdrawal was outside the five-year window, a cash score made in Year 1 would estimate a $50 loss to the federal government.

The NPV score, on the other hand, is much different because it simultaneously accounts for the up-front loss of $50 in revenue and the later collection of $55. But not so fast: the government didn’t actually make $5. Because the U.S. government didn’t take in as much money in Year 1, more deficit spending occurred, which increased the federal debt.4 Assuming that the U.S. government borrows at about a 3-percent rate, $55 received in Year 6 is worth $47 today, which yields the NPV a cost of $3 to the federal government.5

Full disclosure: NPV cost estimates have their drawbacks, too. In particular, making an NPV calculation today requires many assumptions, including: future interest rates, when the money will be withdrawn, the rate of earnings on assets, and the difference between the account holder’s tax rate when they contribute and when they withdraw those funds. Being far off on any of those counts will skew the NPV score.

Unlike a cash estimate, using an NPV approach also inherently involves behavioral assumptions ? in other words, forecasting what would have happened with the money had tax deferral not been available. Would workers have saved the same amount in a taxable account? Or would workers have saved less and spent more immediately?6

All of these assumptions add up and mean that an accurate NPV estimate of tax deferral is a difficult task, but a substantial body of research on defined contribution savings vehicles could help budget scorers select reasonable assumptions. For example, evidence suggests that the savings resulting from the implementation of automatic features (such as auto-enrollment) are substantially new savings (i.e., people reduce consumption to save). Furthermore, CBO and JCT are already in the business of making comparable assumptions for many of the estimates that they are asked to do.

The Bottom Line

Despite the fact that building assumptions can be difficult, we know that the existing cash scores of retirement tax benefits misrepresent the true cost to the federal government. In the case of deferral, NPV estimates help to account for the eventual taxation of contributions and earnings, while for Roth, NPV estimates reflect the cost associated with never taxing the growth of savings. BPC’s Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings will be taking a close look at tax incentives for retirement savings and plans to make use of both cash and NPV estimates to fully understand the impact of retirement tax incentives.

Alex Gold served as a policy analyst for BPC’s Economic Policy Project. Shai Akabas and Brian Collins contributed to this post.

View all posts in BPC’s Retirement in America series under Related Stories below.

1 JCT, which is the government entity that scores tax deductions, credits, and exclusions, usually uses a five-year window for tax expenditure estimates. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which scores all federal spending programs, usually uses a ten-year window. All legislation that is voted on by Congress must be scored over ten years.

2 Employer contributions are also exempt from payroll taxes.

3 Other than in special cases, those who withdraw funds from a 401(k) plan or IRA before age 59 ½ face an additional 10-percent tax penalty on their withdrawal.

4 This issue may sound a bit like the “dynamic scoring” one that has recently drawn substantial attention in Congress, but the two are effectively unrelated. The NPV issue arises due to the fact that legislation is scored using a 10-year budget window, whereas dynamic scoring is a question of whether macroeconomic effects should be incorporated into budget estimates.

5 For simplicity, this example assumes no inflation.

6 This question is particularly important when estimating the cost of Roth accounts. For an estimate of the federal government’s lost revenue from the inside buildup in Roth accounts, one must know or guess how much of those investment earnings would actually happen (and thus produce revenue) in the absence of such savings vehicles.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.