Water Week Spotlight: D.C.’s Environmental Impact Bond

March 19 marked the start of Water Week, a timely reminder that investing in our nation’s water and wastewater systems is a national priority. Facing staggering costs to modernize this critical infrastructure, many local officials are turning to innovative solutions. In one such effort, the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority, known as DC Water, issued the nation’s first environmental impact bond (EIB) late last year. The proceeds will be used to construct environmentally-friendly stormwater infrastructure. The $25 million tax-exempt bond is just a fraction of a $2.6 billion investment mandated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Yet the District’s move is instructive; water infrastructure is a top-of-mind consideration in most communities, some of which face a similarly steep cost to comply with water quality standards. While D.C.-bashing is a popular political pastime, local leaders deserve credit for engaging private capital in a results-oriented and innovative way.

EIB Structure

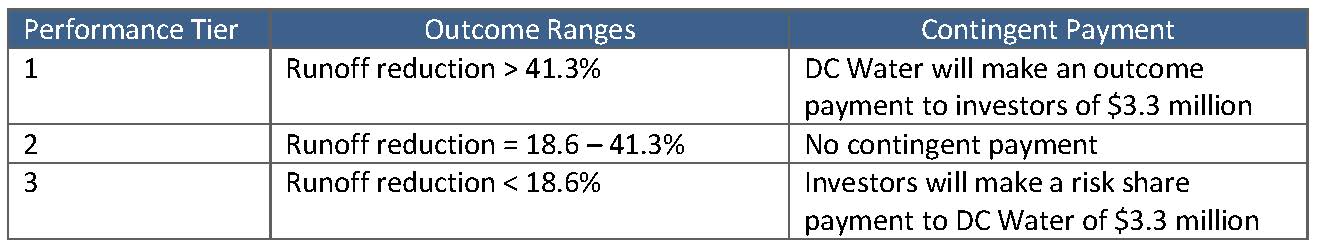

Many pay-for-success projects have been launched in recent years to achieve desirable social outcomes like reduced homelessness, yet D.C.’s EIB is a novel application of this model in infrastructure finance. It is structured similarly to any other tax-exempt municipal bond, but with an additional payment that is based on the infrastructure’s performance (as shown in the table below).

Source: DC Water

D.C.’s EIB is essentially a pilot program testing the effectiveness of environmentally-friendly infrastructure in reducing stormwater runoff, used here as a proxy for limiting polluted overflow into local waterways. With billions committed to new, massive stormwater tunnels, DC Water has instead decided to assess whether a portion of that would be better invested in low-impact development, such as permeable pavements on streets and alleys, raingardens, and downspout disconnections to direct water from rooftops into rain barrels. The true innovation is not necessarily the infrastructure being built or the bond structure itself, but the way DC Water is reallocating the performance risk of their infrastructure investment by sharing that risk with private investors.

Benefits and Criticisms

The EIB is allowing DC Water to manage a portion of the risk associated with choosing low-impact development over traditional gray infrastructure like tanks, basins, or deep tunnels that allow for stormwater storage. There are many environmental, economic, and social benefits to low-impact development that underground tunnels simply do not provide. Among them are potentially lower costs, ecological benefits, additional recreational spaces, boosted property values, improved air quality, a reduced carbon footprint, and aesthetically appealing communities. Investors are betting that the infrastructure will perform as well as?or better than?expected. But if not, DC Water will be able to recoup some of its investment.

Across the United States, capital investment needs for wastewater and stormwater systems are estimated to total $271 billion over the next 25 years.

DC Water was able to find a market for their EIB; it was privately placed to Goldman Sachs and the Calvert Foundation with an initial interest rate of 3.43 percent, comparable on a cost of funds basis to its historic cost. With a growing market of investors actively seeking products that take into account environmental, social, and governance factors, DC Water’s effort may prove there is an appetite among investors for bonds of this nature and encourage similar or larger deals in the future.

The bond itself has not been the object of much criticism to date, but local environmentalists and political activists at various points in development have expressed concerns about the project’s limited scope and delays (buying time to spread out construction costs while delaying remediation of the problem). Project construction and performance evaluation will take several years and required an EPA deadline extension, but DC Water is hoping to create a “replicable and scalable approach” to financing environmentally-beneficial infrastructure. There may also be lessons to learn about risk allocation that are applicable beyond the water sector.

Why Other Cities Should Take Notice

Across the United States, capital investment needs for wastewater and stormwater systems are estimated to total $271 billion over the next 25 years. D.C.’s effort is notable because many cities are similarly grappling with how to design and pay for water infrastructure generally and whether to rely on traditional gray infrastructure or incorporate low-impact development, which might include green roofs, raingardens, permeable pavements, and other options. Some cities have been skeptical of the role low-impact development can play in controlling stormwater runoff and resulting overflows. Others, like Philadelphia, have gone all in.

Examples of Low-Impact Development

Clockwise from top left: a stormwater bumpout, raingarden, stormwater basin, and stormwater tree trench; Source: Philadelphia Water Department

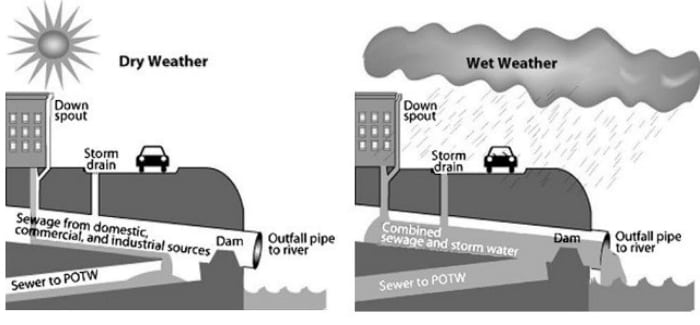

The potential of low-impact development is particularly important to the more than 770 communities in the United States with combined sewer systems like the District’s. These systems, a water infrastructure innovation of the 1850s, carry sewage and stormwater together (as opposed to having separate pipe infrastructure) and can be found in many of America’s older cities and neighborhoods. When the capacity of a combined sewer system and its treatment facilities is overwhelmed during heavy rainfall, sewage and polluted stormwater are directed into local streams and rivers through combined sewer overflows, or CSOs. Researchers have shown that CSOs can have serious public health implications in addition to their environmental impact, i.e. waterway pollution.

Typical Combined Sewer Overflow System

Source: EPA

According to the EPA, combined sewer systems release approximately 850 billion gallons of untreated wastewater and stormwater each year. In the District alone, more than 2 billion gallons of diluted sewage flow into Rock Creek and the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers in a year of only average rainfall.

For years, the EPA has entered federal consent decrees to mandate that cities, including Washington, eliminate most CSOs and often impose steep compliance costs and deadlines, some of which are decades-long. A rundown of major systems with these decrees in place shows that over $30 billion is needed to bring CSOs into compliance, with these systems in various stages of making those investments. A common method to address CSOs is building gray infrastructure to allow for the storage of stormwater until wastewater treatment plants have the capacity to treat it. In fact, several tunnels were planned and remain the primary expense in DC’s Clean Rivers Project, the $2.6 billion long-term program to control CSOs in D.C.

To the ire of many mayors and local officials, EPA-mandated retrofits of combined sewer systems often come with a hefty price tag: $4.7 billion in St. Louis, $1.3 billion in Seattle and King County, Washington, and $3.1 billion in Cincinnati, for example. DC Water’s EIB could be an important model for other cities in determining whether low-impact development can be both a cost-saving and successful intervention for addressing stormwater management and improving water quality.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.