Policy Check-In: Status of Airport P3s in the U.S.

When President Trump announced his support for air traffic control (ATC) reform and released a set of guiding principles to kick off the White House’s infrastructure week, policymakers were quick to opine on the plan’s potential and pitfalls. In particular, some critics denounced privatizing such an important public asset. Setting aside the merits of ATC reform, which have long been recognized on both sides of the aisle, members of Congress should not conflate ownership issues in ATC reform with a broader infrastructure priority, attracting private capital to public infrastructure and encouraging public-private partnerships (P3s).

Investments in airport facilities, of which the ATC system is only one piece, are a top-of-mind consideration for many local leaders. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) projects that passenger enplanements will jump 46 percent over the next 20 years, along with consistent growth in cargo traffic, underlining how critical airports are to future trade, travel, and economic growth. As Congress and the administration work to put forth an infrastructure plan, one that aims to attract private capital, innovation, and expertise, and reauthorize the FAA, lawmakers should be particularly mindful of three key points:

- Despite many international and domestic examples of their potential, partnerships with the private sector are an underutilized tool to modernize airport facilities, increase efficiency, and reduce costs.

- Several key barriers prevent greater consideration of these partnerships and must be addressed to realize their attendant benefits.

- Policy options to unleash the potential of the private sector in meeting our airport infrastructure needs should fully reflect bipartisan infrastructure priorities.

Funding and Financing

Concerns about the state of our airport infrastructure, including more than a few disparaging comments from the likes of President Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, have not yet translated into legislative action. The Airports Council International – North America (ACI-NA) estimates $99.9 billion is needed over just the next five years to accommodate growth, maintain existing facilities, and continue to meet standards. Over the same timeframe, the FAA estimates $32.5 billion is needed, though their estimate does not account for air traffic control facilities, all projects regardless of eligibility for federal Airport Improvement Program (AIP) grants, and security projects.

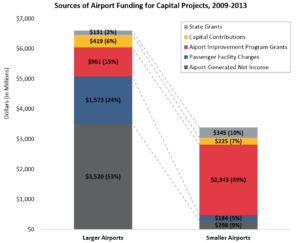

Generally, airports have access to several potential sources of funding to meet these capital improvement needs: state grants, capital contributions (from airport sponsors or entities that use the airport), federal AIP grants, Passenger Facility Charges (PFCs), and airport-generated income. However, these funding sources can be insufficient and their use restricted. For example, most revenue-producing airport projects, such as ticket counters and concessions, are not eligible for AIP grants. AIP grants also come with strings attached, called grant assurances, including prevailing wage rules, limitations on the use of airport revenues, and reporting and planning requirements.

Congress has authorized airports to collect PFCs on each boarding passenger, but use of that revenue for capital projects is contingent upon FAA approval and collections are capped under federal law at $4.50 per flight segment or $18 per roundtrip. Airports that impose PFCs can also then become ineligible for a portion of AIP formula grants they would otherwise receive. According to the Government Accountability Office, two-thirds of eligible airports are approved to collect PFCs and 90 percent of those do so at the maximum allowed rate. As such, some stakeholder groups and lawmakers have proposed raising the cap or indexing it to inflation.

As shown in the figure below, the availability of these buckets of funding can also vary by the size of the facility. Larger airports usually generate and use PFCs and income from airport tenants, concessions, parking, and more for new projects, while smaller airports rely more heavily on AIP grants from the FAA. Tax-exempt bonds, mostly private activity bonds, are also widely used to secure additional upfront funding, though they are not included in the figure below as debt financing must be repaid. Exempting the interest on such bonds from taxes is a primary way the federal government supports airport development projects.

Source: Government Accountability Office[i]

The Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF) is the primary funding source for the AIP grant program, along with several other federal aviation programs, with taxes on tickets, cargo, and aviation fuels making up its revenue sources. In recent years, changing airline business practices?such as separating charges for certain airline services and amenities like checked bags and wi-fi access from the base ticket price and not subjecting them to the same taxes?are considered to adversely impact AATF revenue streams, which may jeopardize a critical source of funding for airport projects, especially for small and rural facilities.

According to ACI-NA, airports generate about $10 billion annually to fund infrastructure projects, leaving them more than $10 billion short. They identified terminal buildings, airfield capacity, reconstruction, and surface access as the most pressing needs. Small airports, though, face disproportionately higher development costs than medium and large airports in meeting safety, security, and capacity challenges. Overall, U.S. airports are very safe and flights are mostly on-time. Yet congestion at airports is growing and many facilities are aging. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, a small number of larger airports also experience chronic capacity constraints and regular delays, which in turn can have a domino effect on the rest of the air transportation system. While many airports can generate needed revenues and secure financing, existing funding sources can be insufficient for others and are certainly constrained by federal policies.

Partnerships with the Private Sector

Private ownership and integrated management of airport operations is relatively rare in the United States. Almost 98 percent of the more than 3,300 airports tracked by FAA’s National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems are owned by public entities, while just 77 airports are privately owned. Internationally, the privatization of airport facilities is far more common. For example, over 40 percent of European airports are wholly or partially owned by private shareholders, handling about 75 percent of passenger traffic each year.

Regardless of the statistics, the private sector is already heavily involved in many aspects of U.S. airport operations, including airlines, terminal concessions, jet fuel delivery, and more. Service and management contracts transferring some operational responsibilities to private companies have also been used in the United States. Some airport expansion projects are even financed through revenue bonds guaranteed by major tenant airlines. Despite extensive private sector participation, the consideration of public-private partnerships (P3s) to improve the delivery of airport improvement projects is still nascent. We consider P3s to encompass the full range of potential partnerships with the private sector, from individual projects, such as a contract to modernize and operate a terminal, to airport leases and sales, which could entail full or partial ownership by the private partner.

American airports are predominately owned by local governments and regional authorities, which can make them subject to political risks. As with other types of infrastructure, many of these local governments and authorities are increasingly strapped for funding. Partnerships with the private sector, whether through a particular project or asset acquisition, can allow needed rehabilitation or expansion projects to move forward, while bringing efficiencies and innovations that may not have otherwise been considered.

Managing the construction, operation, and maintenance of airport facilities can be difficult and risky, whether from preserving full operational capacity throughout construction or adhering to airport safety regulations. P3s often make the most sense when considerable risks can be transferred from the public owner to a private partner. Even a cursory look at the construction plans for Los Angeles International Airport and New York’s LaGuardia Airport highlights the complexities inherent in these multi-year, multifaceted modernization projects. Airports, especially larger facilities, also generate a substantial amount of revenue without state or federal assistance, making them ideal candidates for programs like asset recycling, which was highlighted in a previous BPC blog. The table below highlights a few examples of P3 projects underway or completed in the United States.

[table “” not found /]Share

Read Next

U.S. Airport Public-Private Partnerships

| Project | Summary |

|---|---|

| Austin-Bergstrom South Terminal | The City of Austin, Texas, as the owner and operator of the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, entered into an agreement with LoneStar Airport Holdings to invest about $12 million for the rehabilitation of its South Terminal. The South Terminal had previously been vacant, and investment was needed to add airport capacity and attract budget airlines with an upgraded limited services terminal. The private partner is also responsible for building and operating the facility under the 30-year lease and concessions agreement. The renovated terminal opened in 2017. |

| Branson Airport | Branson Airport is a commercial airport outside Branson, Missouri that was privately developed and is privately operated. The $155 million facility was financed with a mix of private equity and tax-exempt private activity bonds. Without federal funding and related regulatory requirements, construction took just 22 months. Notably, the airport has struggled since its completion in 2009 to attract airlines and serve the number of passengers that had been initially projected. As such, Branson Airport LLC, the private operator, has entered into a forbearance and funding agreement with the bondholders’ trustee. |

| JFK International Air Terminal | To replace John F. Kennedy International Airport’s original International Arrivals Building, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey partnered with the JFK International Air Terminal LLC (JFKIAT), a consortium including Schiphol, Lehman Brothers, and LCOR (now Schiphol USA and Delta Air Lines). Per their agreement, JFKIAT was responsible for building, operating, developing, and managing a $1.4 billion modernization effort. Access to tax-exempt bond financing helped to make the project viable. The project was completed on time but with construction costs 20 percent over its budget, requiring JFKIAT to obtain completion financing from the Port Authority. Passenger projections were also initially off, particularly after September 11, but volumes have since recovered and revenues have increased. |

| LaGuardia Central Terminal | With LaGuardia Airport’s aging and capacity-constrained facilities, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey entered an agreement with a consortium of private companies to replace the Central Terminal Building, a key part of a multifaceted plan to upgrade the airport and nearby infrastructure. The private partner is responsible for financing two-thirds of the $4 billion project in a DBFOM deal that will last 35 years. The project is currently under construction. |

| San Juan Airport | Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was privatized in 2013 through the FAA’s Airport Privatization Pilot Program. The public airport owner, the Puerto Rico Ports Authority, and the Puerto Rico P3 Authority, partnered with Aerostar—a 50-50 venture between Highstar Capital, an infrastructure investor, and Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste SAB de DV, which operates nine airports in Mexico. The process took four years to complete and resulted in a 40-year lease agreement. |

Several other airports, including Denver International Airport, Kansas City International Airport, Los Angeles International Airport, and San Diego Airport, are in the procurement process or considering P3s but have not yet finalized project agreements. As these projects advance, they may provide valuable information for other local governments pursuing innovative partnerships with the private sector.

To produce alternative sources of capital for airports and realize some of the benefits previously mentioned, Congress authorized the Airport Privatization Pilot Program in 1996. Since then only two airports have been privatized, with one reverting back to public control after a few years. St. Louis Lambert International Airport, Westchester County (New York) Airport, and Hendry County (Florida) Airglades Airport are currently in some stage of the application process. The program was initiated based on the premise that the removal of certain economic and legal impediments would promote privatization. However, as currently structured, the program has failed to attract much interest for several reasons, including:

- Application and approval procedures for the pilot program can be lengthy and resource-intensive.

- Tax defeasance rules require a private partner to defease or repay any debt supported by tax-exempt bonds when acquiring an airport asset.

- Privatized airports are eligible for fewer federal grant opportunities.

- Permitting delays and extensive regulatory approvals for airline operations add layers of uncertainty that discourage private investment.

Both the Government Accountability Office and Congressional Research Service have released reports analyzing these impediments and limitations.

While Congress could consider tweaks to the privatization pilot program to build interest, BPC has also proposed policy options to make public infrastructure more attractive to private capital and provide local governments with the expertise and capacity to protect the public interest when pursuing P3s. Amending regulatory impediments, expanding and creating new financing options, expediting permitting, and developing new capacity-building programs could go a long way in helping modernize our airport infrastructure and should be incorporated into plans for an infrastructure bill.

[i] Note: Larger airports include large and medium hubs. Smaller airports include small hubs, non-hubs, nonprimary commercial service airports, relievers, and general aviation airports. More information on FAA classifications can be found here.

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.