How could “asset recycling” work in the United States?

As was mentioned in the administration’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2018, leveraging private investment will likely be a significant aim of any new infrastructure plan. Public-private partnerships (P3s) are widely used internationally to build, upgrade, and maintain infrastructure, but are still a largely underutilized tool in the United States.

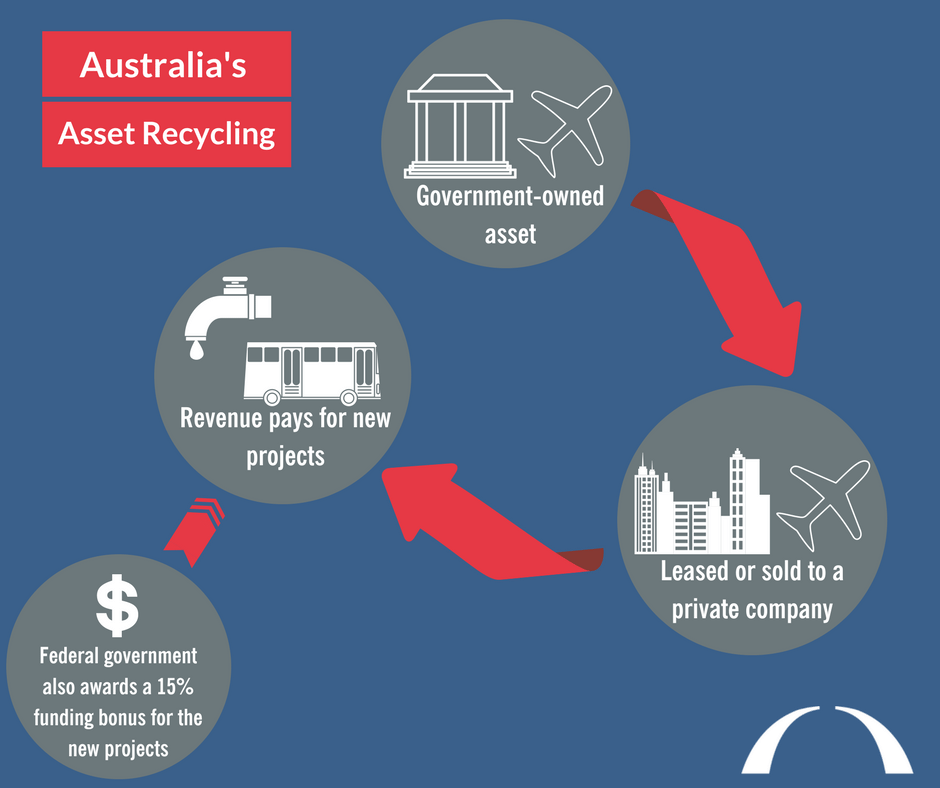

To help kick-start the consideration of P3s, a new concept has recently been percolating around Washington: “asset recycling.” An innovative mechanism first used in Australia, asset recycling allows existing, publicly-owned infrastructure to be leased or sold to a private partner with the lease or sale revenues used to fund new projects. In Australia, the federal government incentivized recycling during a two-year program by awarding the public agency with an additional 15 percent of the original deal for the new projects. For example, the New South Wales government leased its electrical transmission system to a private partner and used the revenue and the federal grant to fund the Sydney Metro and other vital road and rail projects.

How it Works

The first step in asset recycling is for public agencies to identify assets that are unused or underutilized?such as vacant lots or buildings?and assets they may no longer want to own or manage?such as airports, bridges, or parking facilities. Ideally, agencies would do this after taking a comprehensive look at all existing assets through a formal asset inventory. At that point, agencies have two options: they can either have a “garage sale” and sell the asset, or they can lease the asset to a private company who is tasked with handling its operation and maintenance, including all attendant costs. Ownership remains unchanged, and the owner receives compensation for the negotiated term of the rental. However, many of the risks of ownership, like unexpected repairs, are fully transferred to the lessee. It’s as if you rented out your home and the tenant fixed it up for you before handing back the keys.

Using these two options, the asset recycling model found success in Australia, leveraging $20 billion of private investment from $5 billion in federal funding. Importantly, the funding was used for any type of infrastructure project desired by the sponsoring state, even for assets that do not generate revenue, thus alleviating some pressure on federal and state budgets. One of the most beneficial effects was stimulating public-private project development. As we have addressed before, there are several existing barriers to leveraging private capital and creating more P3 projects in the United States. Adopting an asset recycling program customized to American needs could go a long way in addressing some of these barriers.

Benefits

First, asset recycling enables public sector partners to monetize underutilized assets. For instance, through an inventory of its vacant lots, New York City discovered that it owned over 1,100 of them. They can now put a price tag on those lots and either sell or lease them to the private sector and use the proceeds from the transactions to fund much-needed improvements to other infrastructure assets.

Secondly, owning infrastructure assets comes with a cost?namely operations, regular maintenance, and sometimes emergency repairs. Even in cases of vacant land or buildings, the public sector may not be using the property but it is likely paying some operations and maintenance costs for the asset. Such costs are rarely factored into financial analyses to assess their overall impact on public budgets. However, by selling or leasing those assets, not only does the public sector acquire capital, it may transfer the long-term operation and maintenance costs and risks to the private partner. The public partner no longer needs to concern itself with paying for sudden and unpredictable cost increases associated with aging infrastructure assets.

Finally, this could be a very useful tool for both urban and rural communities. In urban areas, it could attract new private partners who could take over the old asset while generating revenues for improvements to other assets, like nearby roads or transit systems. Further, states could use asset recycling to generate revenues needed to pay for infrastructure upgrades in rural communities that lack the economies of scale to raise funds themselves.

The United States version of asset recycling could be the cornerstone to leveraging significant investment from the private sector and creating modern infrastructure.

Challenges

Notably, the United States has a unique infrastructure environment that differs from Australia in several areas that could complicate the adoption of this model. The characteristics of which assets local, state, and federal governments own in the United States are different from their Australian counterparts, as is the public appetite for private ownership of certain utilities. For example, it may be challenging to find opportunities to replicate the project mentioned earlier of an electric transmission system being leased to a private company, as 70 percent of electricity in the United States is already provided by privately operated utilities. On the other side, selling or leasing one of the remaining public electric transmission facilities to the private sector could prove more popular than, say, a road or water project, as Americans are generally comfortable with private provision of electric services. The types of assets that are deemed eligible and prioritized for asset recycling will be a crucial component to creating a successful program.

Australia has also found success with this model, in part, by utilizing lengthy leases that stretch from 50 to 99 years. In the United States, some of the most controversial P3s have seen criticism revolve around the length of the deal. One of the primary critiques of Chicago’s much-criticized parking agreement is that it spans 75 years. If long-term lease agreements are a prerequisite to attracting private capital, public agencies will need the technical capacity and expertise to incorporate performance metrics into the agreement and exercise oversight.

The Chicago parking agreement and other P3s have also been criticized for shifting too much of the power over tolls or fees to the private partner. Asset recycling agreements may need to incorporate provisions that govern the frequency and size of any increases or revenue-sharing arrangements to avoid the perception that the private company will unjustly profit from the transfer of the asset. Clear and frequent communication about the public benefits of the arrangement will be essential to earning and retaining public support.

Going forward

Policymakers will need to be mindful of these differences and of the necessary pre-development capacity that will need to be in place at the state and local level before a new federal initiative will be able to succeed. In some states, enabling legislation will need to be enacted to allow public agencies to enter into asset recycling agreements. The Bipartisan Policy Center has previously recommended solutions to address these issues, which should be included in any new federal program to incentivize asset recycling:

- Incentives to develop asset inventories: Efforts to identify assets for recycling will be significantly more effective if public officials have a comprehensive, life-cycle inventory of every infrastructure asset that they own and operate. Creating these inventories is the precursor to both effectively leveraging private capital and to unlocking improved strategic planning.

- Funding for P3 offices and predevelopment costs: State or regional P3 offices bring needed expertise to infrastructure agencies. Today, there are very few of these offices in place, but where they do exist, such as the P3 offices in Virginia and the District of Columbia, they serve as the principal resources in forging these partnerships. Such expertise, coupled with funding to pay for the planning, scoping, and financial analysis that must be done by public agencies before a project is put out for bid, are necessary components of an asset recycling program.

- Clear criteria and adequate oversight mechanisms: While decisions about what assets to recycle, specific lease terms, and use of lease proceeds should primarily be in the hands of state and local officials, the federal government has an important role to play in determining which projects receive federal incentive grants. Criteria for the program should emphasize public benefit and protection of the public interest throughout the term of the lease.

If these principles are included, the United States’ version of asset recycling could be the cornerstone to leveraging significant investment from the private sector and creating modern infrastructure.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.