Fear Wins: Erdogan’s AKP Victorious in Turkey Election

Blaise Misztal, BPC’s director of national security, was on the ground in Turkey this weekend to view the election.

The scene might have been familiar in Turkey this weekend?another parliamentary election just five months after the last failed to result in a government?but the mood and the result were starkly different compared to the vote in June. Where optimism seemed to reign in the summer, fueled by the hope that the country’s problems and divisions could be resolved democratically, resignation and despondency had taken its place. And whereas balloting in June had yielded a political stalemate, in November, President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) secured a resounding, if surprising, victory.

But that victory came at a steep cost for the country. Turkish society bears deep scars from the past five months of political uncertainty, spiraling violence, ramped up authoritarianism, ever greater fragmentation and distrust. The central question now is whether Turkey can recover from this strife and, more pressingly, whether it can do so under Erdo?an and the AKP.

Results

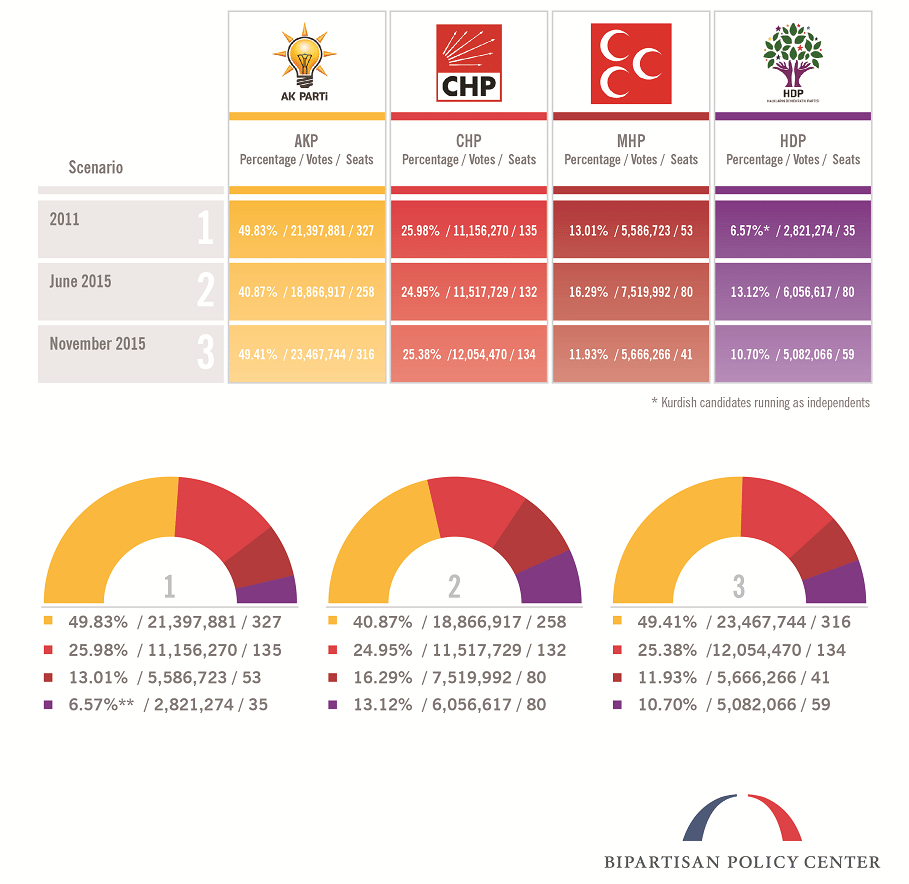

Looking back, two key dynamics drove the June 2015 parliamentary election outcome. One was the sharp decline of the AKP vote share to 40.8 percent in June from 49.8 percent in 2011. The other was the emergence, for the first time, of a nationwide pro-Kurdish party, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), that successfully crossed the 10 percent electoral threshold with 13.1 percent of the vote (compared to 6.6 percent for pro-Kurdish candidates running as independents in 2011). The combined result denied the AKP a parliamentary majority and ushered the HDP into parliament.

Both of those trends reversed in the November election. The AKP’s portion of the vote surged back up to 49.8 percent, bearing a striking resemblance to its performance in the 2011 elections. The HDP dipped, and although it still surpassed the threshold with 10.7 percent of the vote, it fared worse than in June and disappointed expectations that it had momentum.

With such a strong performance, the AKP will form a single party government with about 316 of the 550 seats in Turkey’s parliament. This is only a few seats shy of the three-fifths majority (330 seats) needed to call for a public referendum on the constitutional changes that Erdo?an has long been seeking. Also, notably, the HDP earned more seats than the National Movement Party (MHP) despite winning a smaller percentage of the total national vote. This is because seats are allocated at the provincial level and HDP’s votes were highly-concentrated in the southeast, where it won a majority of votes in 12 provinces. MHP, on the other hand, did better nationwide but failed to secure a majority in any single province.

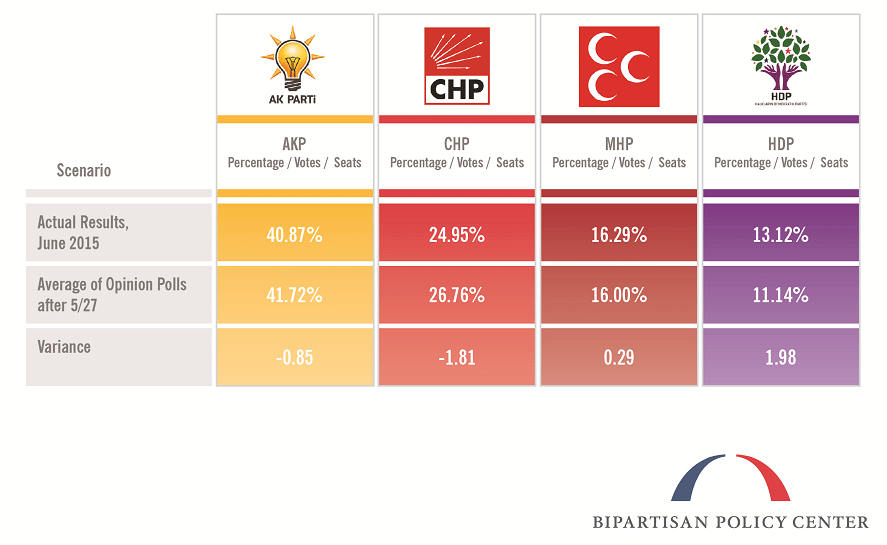

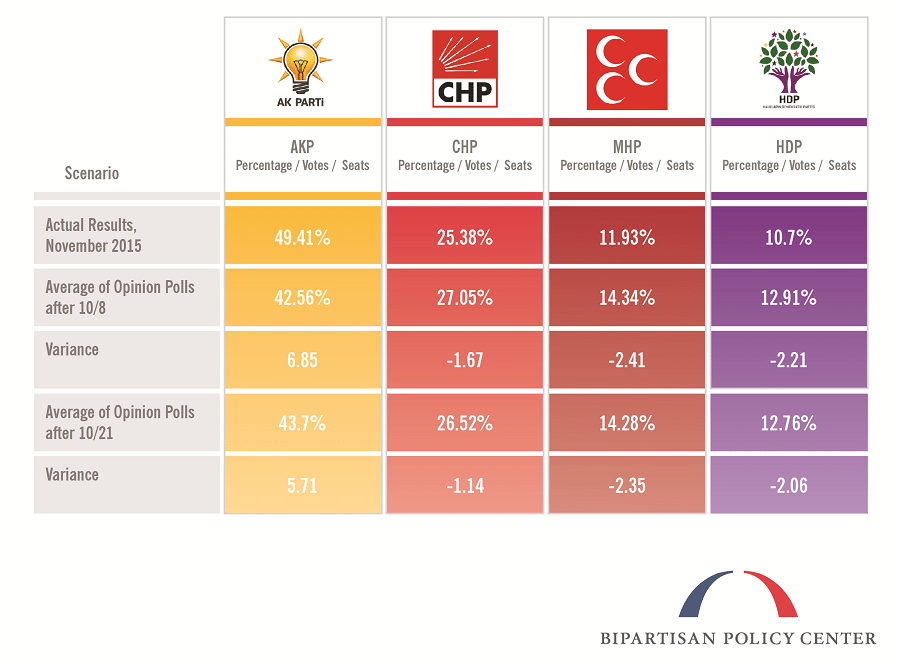

This result is surprising not only for the stark reversal in the AKP’s fortunes, but more improbably because it is so out of line with what public opinion polling was suggesting in the run up to the election. Although opinion polls in Turkey are of questionable reliability, given that many of the polling firms are considered to have political leanings and, more recently, that the government has engaged in intimidation of pollsters, they were somewhat accurate in predicting the June election.

But for the November election, the polls were much wider off the mark when it came to the AKP outcome (and also those of the MHP and HDP). While polls showed a general uptick in support for the AKP as the election drew closer and especially following the terrorist attack on a peace rally in Ankara on October 10, no poll?including the most skewed outliers?showed the AKP earning more than 47.2 percent of the vote and the average was much closer to 43 percent. Similarly, in no poll did the HDP do worse than 11.5 percent and the average was much closer to the high 12 percent range.

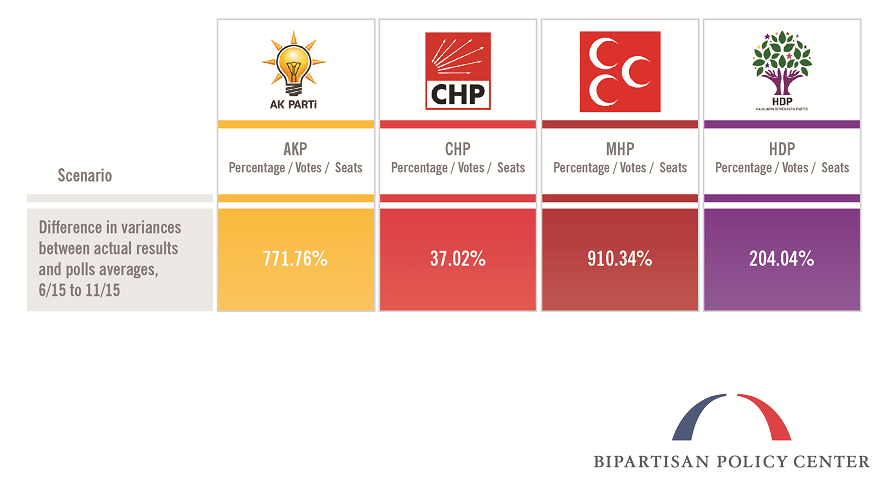

Notably, the polls turned out to be an order of magnitude less accurate in predicting AKP, MHP, and HDP vote totals. Even more interestingly, they erred in the opposite direction than previously. In June, polls underestimated the AKP’s result and overestimated the results of the MHP and HDP. In November, it was the opposite. AKP far outperformed the polls and MHP and HDP did far worse than predicted. Polls for CHP, however, remained close to the mark in both elections.

How the AKP Won

The AKP won 4.5 million more votes in November than they did in June. Where did they get these votes? Assuming they were won freely?without resorting to tactics such as ballot-stuffing or otherwise manipulating the actual casting and counting of votes?these votes were still won through fear. But that assumption of a free election should not be taken for granted given the discrepancy between polling predictions and the outcome, as well as the reports of voting irregularities.

A Bipartisan Policy Center analysis showed that the AKP lost votes among two groups in the June election: Kurds and nationalists. Kurds switched to HDP because they were concerned that the AKP was not doing enough to pursue a peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)?considered a terrorist group by Turkey and the United States?while many nationalist Turks ended up voting MHP because they believed the AKP was being too lenient with the PKK. Erdo?an had long tried to keep both blocs of voters under the AKP banner by trying to please them both?making peace overtures to the Kurds while riling crowds with nationalist rhetoric. This strategy clearly failed in June 2015 and there was little reason to believe that it could be revived. Thus, to regain a majority in the November snap election, the AKP would have to choose one of these two groups to try to win back. Our analysis suggested that “the AKP’s most viable and pragmatic option is to pursue, unrepentantly, nationalist voters who switched to the MHP,” and that is precisely what Erdo?an did.

Seeking to convince voters that the alternative to a strong, single party government must be chaos, Erdo?an engaged in a strategy of calculated destabilization while fiercely attacking his opponents. The resumption of hostilities against the PKK, after a two-year ceasefire, brought renewed violence to Turkey and allowed Erdo?an to appeal to nationalist voters, promising to protect the state and defeat the Kurdish threat if only they returned the AKP to power. The PKK conflict also created an opportunity to tar the HDP as terrorist sympathizers while draconian restrictions on press freedoms?including arresting critical journalists as well as inciting mobs against and forcibly taking over opposition media companies?were meant to discredit anyone that did not support the AKP.

This strategy appears to have succeeded in three main ways. First, by raising electoral participation. Roughly 1.4 million more valid votes were cast in November than in June. It is likely that most of these went to AKP from supporters mobilized by the threat they saw facing the country. The mobilization of AKP supporters might be even greater than this number suggests if voter turnout was suppressed among other segments of the population, as seems likely in the insecure southeast of the country. Second, by capturing nationalists. The MHP lost over two million votes between June and November, with most of these likely going to AKP as a result of Erdo?an’s successful manipulation of nationalist sentiment. Third, by convincing some Kurdish supporters to return to the fold. The AKP had enjoyed significant support among religious Kurds in the past, although many of them seemed to have seized the historic opportunity of voting for a Kurdish party in June. Apparently, Erdo?an’s attempt to portray HDP as a PKK proxy was convincing to at least some of these Kurds, as the HDP’s vote total declined by roughly a million. Some of those ballots the HDP lost, though, were likely traditional CHP supporters who voted for HDP tactically in June, to ensure that it crossed the threshold, and returned to CHP in November.

The effect of this dogged pursuit of victory at all costs has been a staggering one socially. Although already divided and polarized, most elements of Turkish society looked to the June 2015 election as a chance to resolve urgent political and social problems at the ballot box. There was a sense that the people’s voice could still affect the direction of the country, even if there were deep disagreements about what that direction should be.

When the November election came, however, weariness and wariness replaced this democratic optimism. Political divisions had become even sharper, deeper, and more ossified. People spoke of their political opponents not just as fellow citizens with different views, but enemies of Turkey who could not be trusted and would stop at nothing. And the problems besetting the country no longer appeared entirely resolvable democratically. Only the most fervent AKP supporters seemed to believe that the election would put Turkey back on more stable footing.

Implications

When it appeared?as the polls suggested?that the outcome of this election would be similar to June’s result with the AKP once again denied a parliamentary majority, there was a multiplicity of different scenarios to consider: would there be a coalition government this time? If so, with whom? If not, would there be yet another election? All these questions are moot now. Although there are still a handful of scenarios that could still play out?the AKP might seek to buy or otherwise secure another 14 votes in parliament to put it at the 330 seat super-majority, for example?the real question now is: how will the AKP rule?

Erdo?an’s winning electoral strategy will prove to be a double-edged sword now that the AKP has been returned to power. On the one hand, he created a need for his leadership by stoking instability. What he has now among the people is not support, but fear. If the threat subsides, if the barbarians are no longer at the gate, the need for his leadership will similarly diminish. However, the AKP was elected on the promise of addressing these threats and returning stability to the country. If they are unable to bring the order and prosperity that they said single party government would return, voters might once again grow disillusioned with the party.

In particular, Erdo?an and the AKP will confront this dilemma between continued provocation and reconciliation in three critical areas: rule of law and civil liberties; the Kurdish issue; and foreign policy, particularly Syria. First, now that they are back in power, will the AKP back off the authoritarian measures that have been put in place and the growing censorship that has muzzled the media or will Erdo?an be emboldened to seek a new constitution and with it new, sweeping executive powers? Second, will Erdo?an seek to put the Kurdish conflict back in a bottle and return to a ceasefire or will he continue the operations that have killed an estimated 2,000 PKK militants in the last two months? Third, and related to the previous question, will Erdo?an align Turkey’s priorities in Syria with those of the United States and begin pursuing ISIS more vigorously or will he continue to attack Syrian Kurds who are U.S. allies in fighting ISIS and thereby undermine U.S. efforts to defeat ISIS?

How Erdo?an and the AKP decide to use their renewed power on these three issues will determine whether they can begin to heal the divisions, both within Turkey as well as between Turkey and the United States, that have taken root in recent years. It might just be that the price Erdo?an paid for this victory will prove too high for the country to pay.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now