Can the Administration Detain All Immigrant Families?

In June 2018, President Trump signed an executive order that instructed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to keep families together during their legal proceedings. The president signed the order to quell criticisms about his administration’s “zero-tolerance policy.” The new policy led to the separation of families after immigration authorities referred their parents for criminal prosecution for violating immigration law (a misdemeanor in most cases). Although such family detention is being challenged in court, to implement the order the U.S. government would have to rely heavily on its detention facilities to hold families together as they await their criminal or immigration hearings. BPC estimates that the potential influx of families and unaccompanied minors will easily surpass the government’s detention capacity for these populations this year, which may limit the administration’s efforts to use detention as a deterrent against unauthorized border crossings.

The lack of space for detained families and unaccompanied children and the increasing delay in immigration court proceedings creates this potential problem. As Figure 1 shows, the government currently has 13,126 beds for this population, including 3,326 family beds operated by Immigration and Customs Enforcement at three locations in the U.S. and facilities for 9,800 unaccompanied minors operated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the Department of Health and Human Services. Media reports and government contracting request documents show that the administration has sought 35,000 additional beds, for an estimated total of 48,126 beds for this group.

Share

Read Next

Current and Requested Housing Capacity for Families and Unaccompanied Children

| CAPACITY CATEGORY | POPULATION | CAPACITY SOURCE | NUMBER OF BEDS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Capacity | Families | ICE | 3,326 |

| UACs | ORR | 9,800 | |

| Requested Capacity | Families | ICE | 15,000 |

| UACs | DOC | 20,000 | |

| Total Estimated Capacity | 48,126 | ||

| Source: GAO, HHS, Politico, CBS |

Source: GAO, HHS, Politico, CBS

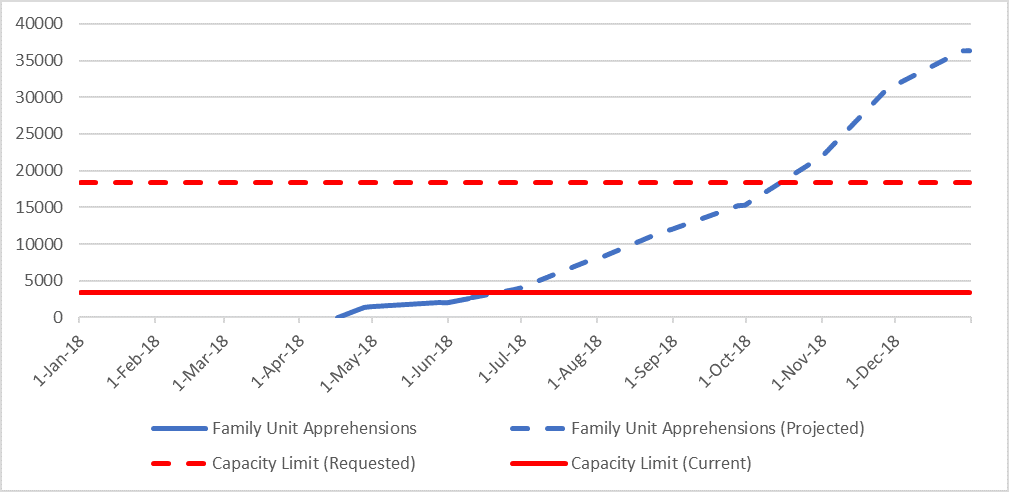

BPC estimates1 of the number of unaccompanied children and family unit apprehensions through the end of 2018 suggest that these populations would rapidly outpace current detention capacity levels. In the case of family apprehensions, we estimate the detained population could grow to more than 36,000 individuals just this year, which accounts for individuals leaving these facilities after an average stay of 58 days. While the requested capacity expansion could delay the onset of reaching the capacity limit, the increase in family apprehensions would supersede this additional capacity by the end of 2018.

Figure 2. Projected Family Apprehensions vs Estimated Detention Capacity (2018)

Source: Marshall Project, Politico, CBS, CBP (1) (2)

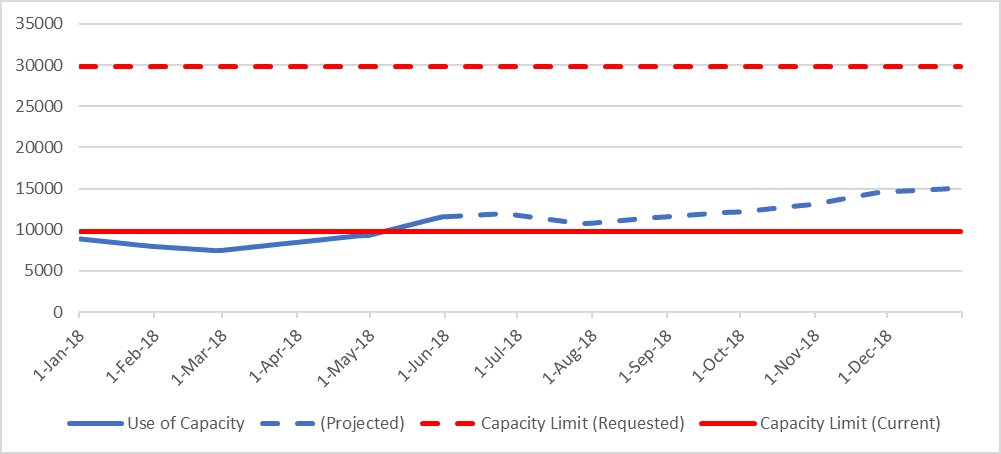

Our estimates find that apprehensions of unaccompanied children may not exceed the government’s space capacity, provided the administration secures its requested housing capacity for this group. As Figure 3 shows, the estimated ORR institutional capacity for this population, 29,800 beds, could meet the projected growth in unaccompanied minor apprehensions through the end of 2018 as children leave ORR custody after an average of 57 days. However, the apprehension figures would supersede the ORR program’s capacity by the end of 2018 without the requested capacity of 20,000 beds.

Figure 3. Projected Unaccompanied Minor Apprehensions vs Estimated Detention Capacity (2018)

Source: ICE, GAO, HHS, CBP (1) (2)

The administration has sought to ameliorate these potential issues through President Trump’s executive order. The order allows DHS to work with other executive agencies such as the Department of Defense (DOD) to locate additional space for families in detention. It also allows DOD to construct new facilities to house these individuals. Given that more families and unaccompanied minors will likely arrive over the summer, these efforts may not expand the government’s housing capacity in time, especially after the controversy over family separations has led some localities to cancel contracts with ICE to house adults and juveniles in their jails. The shortened timeframe to find these spaces may also lead the government to use facilities that do not meet traditional detention standards for minor children.

The shortage in institutional space for families and unaccompanied minors has implications for the “zero-tolerance” policy’s viability. The administration adopted this policy to eliminate “catch and release” measures where children, families, and asylum seekers are released from detention, which the administration says encourages the illegal entry of individuals who take advantage of these “loopholes” by failing to appear at their court date. Given that the administration made detention the key deterrent against these individuals, the shortage in space curtails the policy’s implementation. For instance, this shortage led U.S. Customs and Border Protection to temporarily suspend criminal prosecution referrals for adults with children. The administration’s efforts to alter previous court agreements to detain children and families together beyond 20 days would compound this problem, if it succeeds.

The extensive backlog of immigration court cases further exacerbates this problem. Currently, cases have a waiting period of nearly two years before reaching an immigration judge, forcing the U.S. government to choose between releasing families (with or without monitoring) or using extended detention to ensure they appear for their hearings. Given that the U.S. government lacks the capacity to hold these populations for extended periods of time, it must release many of these families before their hearing date. As we have written previously, an investment in the U.S. immigration court system, including hiring more immigration judges and staff, would address this problem by decreasing the wait time to two to three months, allowing the system to remove undocumented immigrants more quickly and deter undocumented immigration while still addressing its obligations to hear asylum claims. While the U.S. will continue to need detention for certain cases, decreasing the court backlog would eliminate the need to use extended detention as a barrier against illegal border crossings, especially for families.

1 These projections assume that apprehensions through the rest of 2018 will follow the same pattern as 2016 since the historic drop in apprehensions in 2017 appear to be returning to 2016-era levels. The projections consider regular seasonal variation in apprehensions. The models also account for exit from detention or custody by using an entry-exit formula consistent with average stays in immigration detention and custody to determine the growth of the detained population. Figure 2 assumes that the administration adjusts the Flores settlement and can place families in detention for extend periods.

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.