Are “Temporary Workers” Really Temporary? Turning Temporary Status into Green Cards

Under U.S. immigration law, dozens of temporary visa categories allow nonimmigrants to visit, work, or study in the United States for a variety of reasons. Temporary categories have traditionally been considered distinct from permanent migration, providing an opportunity to fill labor shortages or meet other needs without increasing the overall immigrant population. In fact, in most categories, the foreign applicant must prove that they do not have the intent to immigrate before a temporary visa is granted. Nonetheless, there is a strong linkage between temporary and permanent migration, and many “temporary” nonimmigrant workers end up staying in the country for several years and getting green cards. This raises important questions regarding how our immigration system deals with foreign workers and how we use utilize temporary work programs.

Adjustment of Status

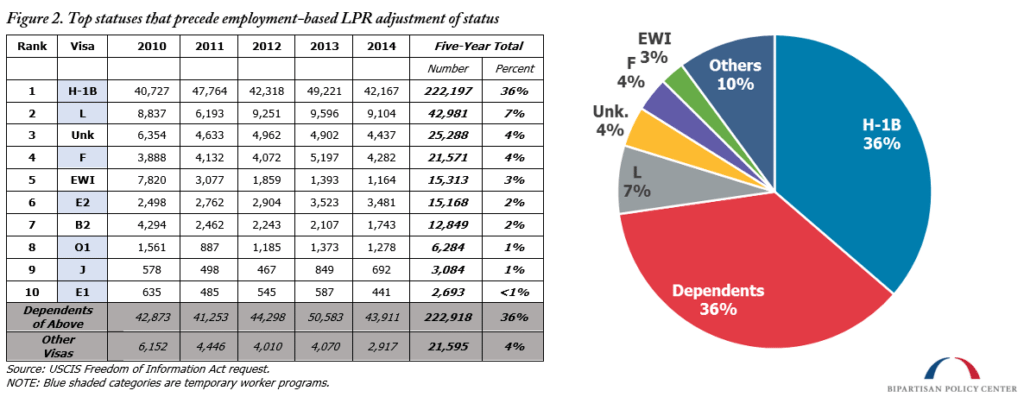

The Bipartisan Policy Center has acquired statistics through a DHS Freedom of Information Act request on temporary visa categories for all individuals who adjusted their status to lawful permanent resident (LPR) in an employment-based (EB) immigrant category in the last five fiscal years (Figure 2 below). While many new immigrants adjust from nonimmigrant status to other permanent categories, such as family-sponsored green cards, the data available and this post focus on which temporary visas most often precede EB categories.

Many critics of current legal immigration levels note that the United States “admits” about one million individuals as permanent residents each year, the most of any country in the world. However, the majority of new green cards issued each year are actually given to individuals who are already living or working in the United States in some kind of nonimmigrant status and are “adjusting their status” to that of permanent resident. In fact, over 58 percent of all new legal permanent residents (LPRs) in the past ten years have been individuals already living in the country in some kind of temporary status.

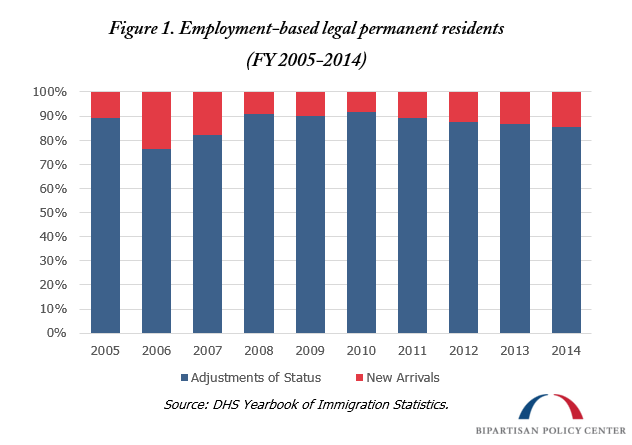

This is particularly true of persons granted LPR status through employment-based categories, which account for about 14 percent of all LPRs “admitted” each year. Out of the nearly 152,000 employment-based immigrants granted LPR status in FY2014 (the last year for which data is available), around 130,000 (or 86 percent) were adjustments of status. Overall in the last ten years, 87 percent of all employment-based LPRs have been adjustments of status (Figure 1).

Temporary to Permanent Transition

The majority of the individuals who adjusted to EB permanent immigrants did so from a temporary worker visa (Figure 2). There are approximately 21 different temporary visa categories that allow foreign persons to work in the United States for a specific length of time. Of these nonimmigrant categories, only H-1B specialty workers and L intercompany transferees are allowed by law to have “dual intent,” which allows nonimmigrants to have immigrant intent and seek LPR status without violating their visa. These visas are often considered “pre-immigrant.” Because of their special dual intent status and the fact that the permanent EB immigrant categories provide more green cards to higher-skilled workers, it is not surprising that more H-1B and L-1 temporary workers eventually permanently settle in the country than other workers. About 43 percent of all individuals that adjusted to LPR in EB immigrant categories between FY2010 and FY2014 were H-1B or L-1 principal visa holders (not including their spouses and children) (Figure 2).

Click on the image to view a larger version of the graphic

While not statutorily recognized as dual intent visas, regulations provide E visas for treaty traders and investors and O visas for individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement some leeway to seek LPR status. Around 24,000 E and O principal visa holders adjusted to LPR between FY2010 and FY2014. In other nonimmigrant categories, including F visas for foreign students and J visas for exchange visitors, the foreign visa applicant must prove that they do not intend to immigrate permanently before a temporary visa is even granted. Nonetheless, the data shows that nearly 25,000 F and J principal visa holders adjusted between FY2010 and FY2014.

The presence of foreign students on the list is of interest. While dual intent is not recognized for F visa holders, many employers hire foreign students after graduation with the intention of sponsoring them for permanent residence or H-1B visas, which have a more direct link to LPR status. Foreign students on F visas are also eligible to apply for Optional Practical Training upon graduation, which allows them to remain in the country for an additional 12 months after graduation for work related to their field of study, with an additional 17 months allowed for students in STEM fields. DHS recently published a final rule that extended the STEM period from 17 to 24 months. The additional time allows F students more time to be sponsored for an H-1B visa, since the H-1B cap is reached each year and it may take multiple attempts for an employer to successfully petition for the individual.

Rounding out the largest nonimmigrant groups of temporary visa holders that have adjusted to LPR status through employment-based categories are B2 visas (visitors for pleasure) and Entry Without Inspection, or EWI. EWI encompasses a class of individuals that entered the United States unlawfully without inspection or a visa1. Lastly, family members of the workers are considered “derivative” applicants and therefore counted against the employment-based numerical limits. Dependents of the principal visa holders in the top ten categories above (Figure 2), including H4, L2, F2, J2, and O3, accounted for about 36 percent of all individuals that adjusted to LPR in EB immigrant categories.

Conclusion

While not all temporary workers want to permanently stay in the United States, the reality is that many foreign nationals begin their path to LPR status through all kinds of temporary nonimmigrant visas. Although the vast majority of individuals who adjust to LPR status are doing so from “pre-immigrant” categories like H-1B and L, thousands more are doing so from various other categories, but have a lesser chance of actually getting a green card because of how the programs are structured in law. For example, F students who are not allowed dual intent must submit themselves to the mercy of the annual H-1B lottery, which randomly accepts a fraction of the thousands of applications received each year. The new regulations expanding Optional Practical Training to three years attempt to resolve some of these issues and provide evidence that even though F visas are not currently considered “pre-immigrant,” they are at the very least “pre-H-1B.”

The trends raise important policy questions about how our temporary and permanent worker programs are structured. Does it make sense that there are few opportunities for students and other nonimmigrants who intend to remain in the country to receive a green card? If employers intend to hire someone permanently, should they have to spend resources and time going through several bureaucratic steps, applications, fees, labor market tests, to hire through so-called temporary programs? A more streamlined and efficient process that recognizes this continuum could balance increased opportunities and choices for immigrants and employers with labor protections and enforcement mechanisms. Continuing to enforce firm separations between temporary workers and green cards as opposed to considering them all “pre-immigrant” does not conform to reality: many are already finding ways to get there anyway.

Oliver Ward contributed to this post.

1 Under current law, such persons are inadmissible and must leave the United States. In addition, the individual could face being barred from re-entry for several years depending on the length of their unauthorized stay (known as the “3- and 10-year bars”). Normally, such individuals would not be eligible to adjust status to LPR in the United States, however, under a previous provision of law (Section 245(i), if the individual was the beneficiary of an immigrant visa petition filed on his or her behalf before April 2001, can adjust status. Cases included in this data set most likely reflect those who adjust under that provision.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.