Ending HIV in America

Policy and Program Insights From Local Health Agencies and Providers

The Brief

The purpose of this Bipartisan Policy Center study is to understand the challenges and opportunities to end the HIV epidemic from the vantage point of frontline health care providers and local health agencies in eight diverse jurisdictions distributed geographically around the country: Seattle, Washington; Bronx, New York; Kansas City, Missouri; Jacksonville (Duval County), Florida; Clark County, Nevada; Scott County, Indiana; Richmond, Virginia; and, Montgomery, Alabama. BPC sought a balance among rural- and urban-focused epidemics; state Medicaid expansion status; and political party of the state legislature and governor. BPC compiled key epidemiologic data from each jurisdiction and conducted 16 qualitative interviews with local health officials and providers.

Since the 1980s, over 700,000 Americans have lost their lives due to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Today, there are an estimated 1.1 million people living with HIV in the United States, with just under 40,000 new cases each year. Thanks to the marvels of modern medicine and public health achievements, HIV is now largely a chronic disease for many with the condition. Unfortunately, health disparities exist, and the epidemic has evolved to become highly heterogeneous across not only populations, but geographically. Federal spending for the domestic HIV epidemic totaled an estimated $28 billion in fiscal year 2019, and the President’s 2020 budget requests an additional $291 million for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to eliminate new HIV infections in the United States.

The purpose of this Bipartisan Policy Center study is to understand the challenges and opportunities to end the HIV epidemic from the vantage point of frontline health care providers and local health agencies in eight diverse jurisdictions distributed geographically around the country: Seattle, Washington; Bronx, New York; Kansas City, Missouri; Jacksonville (Duval County), Florida; Clark County, Nevada; Scott County, Indiana; Richmond, Virginia; and, Montgomery, Alabama. BPC sought a balance among rural- and urban-focused epidemics; state Medicaid expansion status; and political party of the state legislature and governor. BPC compiled key epidemiologic data from each jurisdiction and conducted 16 qualitative interviews with local health officials and providers.

The findings can be categorized into three areas. First, with respect to access to HIV services, the Ryan White Program continues to provide crucial support for low-income people living with HIV and could also be a model for serving individuals at high risk for HIV. Medicaid expansion in 37 states and the District of Columbia has increased access to care for many with HIV, while non-expansion states closely overlap with the regions that are experiencing elevated rates of new HIV diagnoses. There are distinct barriers in rural settings, which are not dissimilar from the broader challenges of accessing health care services in rural America.

Second, with respect to the facilitators and barriers to the HIV response, surveillance efforts are critical to informing HIV programming, but there are often challenges in real-time communications and data exchange. Molecular HIV surveillance holds promise in identifying clusters of infection in local communities. Barriers addressing HIV include poverty and unmet social needs among people living with, or at risk of, HIV. Partnerships with community-based organizations to address social needs can assist in supporting the clinical care plan. Stigma also impedes the HIV response by contributing to HIV risk; stigma-reduction campaigns consistent with local cultural norms may be effective.

Share

Read Next

Rates of New HIV Diagnoses in the United States, 2017 (Per 100,000 People)

- <10.0

- 10.0 - 19.9

- 20.0 - 29.9

- ≥30.0

13.5

3.9

10.9

9.7

11.4

7.9

7.4

13.0

46.3

22.9

24.9

5.7

2.7

9.9

7.8

4.0

4.1

7.9

22.1

2.2

17.0

8.8

7.8

5.0

14.3

8.3

3.0

4.6

16.5

2.5

12.3

5.5

14.0

12.8

4.8

8.8

7.7

4.8

8.5

7.8

14.3

4.3

10.3

15.4

3.7

3.0

10.3

6.0

4.3

4.5

1.7

- <10.0

- 10.0 - 19.9

- 20.0 - 29.9

- ≥30.0

| Alabama |

13.5 |

| Alaska |

3.9 |

| Arizona |

10.9 |

| Arkansas |

9.7 |

| California |

11.4 |

| Colorado |

7.9 |

| Connecticut |

7.4 |

| Delaware |

13.0 |

| District Of Columbia |

46.3 |

| Florida |

22.9 |

| Georgia |

24.9 |

| Hawaii |

5.7 |

| Idaho |

2.7 |

| Illinois |

9.9 |

| Indiana |

7.8 |

| Iowa |

4.0 |

| Kansas |

4.1 |

| Kentucky |

7.9 |

| Louisiana |

22.1 |

| Maine |

2.2 |

| Maryland |

17.0 |

| Massachusetts |

8.8 |

| Michigan |

7.8 |

| Minnesota |

5.0 |

| Mississippi |

14.3 |

| Missouri |

8.3 |

| Montana |

3.0 |

| Nebraska |

4.6 |

| Nevada |

16.5 |

| New Hampshire |

2.5 |

| New Jersey |

12.3 |

| New Mexico |

5.5 |

| New York |

14.0 |

| North Carolina |

12.8 |

| North Dakota |

4.8 |

| Ohio |

8.8 |

| Oklahoma |

7.7 |

| Oregon |

4.8 |

| Pennsylvania |

8.5 |

| Rhode Island |

7.8 |

| South Carolina |

14.3 |

| South Dakota |

4.3 |

| Tennessee |

10.3 |

| Texas |

15.4 |

| Utah |

3.7 |

| Vermont |

3.0 |

| Virginia |

10.3 |

| Washington |

6.0 |

| West Virginia |

4.3 |

| Wisconsin |

4.5 |

| Wyoming |

1.7 |

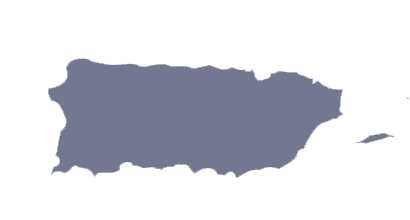

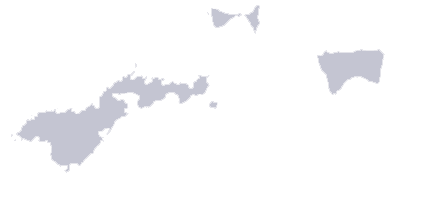

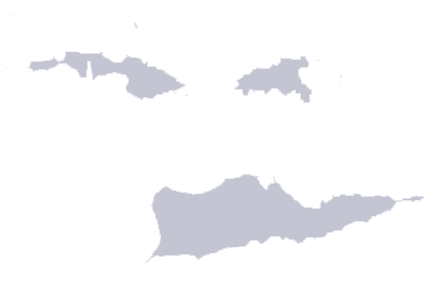

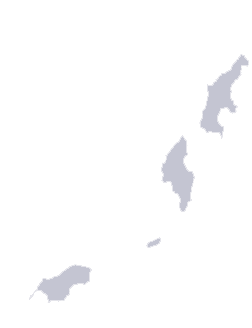

Rates of New HIV Diagnoses in U.S. Territories, 2017

| Territory | Rates of HIV diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|

| Puerto Rico |  | 13.3 |

| American Samoa |  | 0.0 |

| U.S. Virgin Islands |  | 6.5 |

| Northern Mariana Islands |  | 0.0 |

| Guam |  | 3.6 |

| Republic of Palau |  | 0.0 |

Third, with respect to targeted programming, efforts to reach young Men who have sex with Men (MSM) of color are underway across the country given that this population is highly impacted by HIV, but more attention and resources are needed. Elimination of perinatal transmission in the United States is within grasp, though it requires improved coordination across programs and payors; in addition, young people living with HIV remain an important priority for the U.S. health care system. HIV prevention, through the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), has great potential; however, individual, health system, and provider barriers must be overcome. Finally, co-occurring substance abuse epidemics have the potential to exacerbate the HIV epidemic, and thus access to evidence-based treatment and harm-reduction strategies for at-risk individuals are important.

Based on the findings of this study, and consistent with the administration’s HIV initiative, BPC offers the following for consideration by federal, state, and local policymakers to achieve the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90 percent in 10 years.

- Continue to support the Ryan White program. Funding increases would permit state and local programs to invest more deeply in addressing the social determinants of health that stand in the way of full access to HIV care—access that researchers have found reduces

productivity losses and overall costs of illness. - Expand insurance coverage. Stakeholders engaged in ending the epidemic at the local, state, or national level should support the expansion of insurance coverage in all states.

- Improve access to care in rural areas. Federal and state governments should aggressively invest in innovative approaches to increasing access to preventive and care services, including through telehealth, which has been shown to reduce costs and improve access for a

variety of health conditions for rural patients. - Invest in public health infrastructure, workforce, and surveillance. The federal government and states should invest in the public health infrastructure and human resources necessary to maintain robust and interoperable HIV surveillance systems, while strengthening the overall public health system; in addition, increased funds should be directed to efforts to integrate HIV service providers into surveillance systems, allowing data to inform their linkage and retention efforts as well as other provider activities.

- Address unmet social needs. Funding for initiatives such as the Housing Opportunities for People With AIDS program is critical to support people living with HIV; in addition, policymakers at the federal and state levels should consider making some or all of the new funds under the recent federal HIV strategy as flexible as possible to permit innovative local solutions to address social determinants of health.

- Reduce stigma. Addressing HIV requires a policy environment that supports people living with or at risk of HIV; the federal government should consider the impact of policies that harm LGBTQ people, immigrants, women, and other populations.

- Target programs and resources for youth. Federal and state policymakers should assess if there are adequate funds in the Ryan White Program and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants to support this population with a range of social services and peer supports, as well as HIV prevention and care.

- Maintain focus on maternal health, vertical transmission, and pediatric care. Efforts should be made to ensure that specialty obstetrical, maternal and pediatric infectious disease care remain widely available, especially in rural areas of the country with fewer health facilities and subspecialty services; in addition, dedicated efforts should be focused on reducing racial disparities in new infant infections, including increased access to case management, mental health, and substance abuse services for pregnant mothers.

- Prioritize equitable access to PrEP. PrEP should be prioritized as part of comprehensive primary care and federal funding streams, with a focus on men of color who have sex with men and women of color; all efforts should be made to increase awareness and access to PrEP.

- Increase programs to address HIV and substance use disorders. Congress and states should consider broader implementation of evidence-based harm-reduction interventions, such as syringe service programs, which are effective in HIV prevention and do not increase

drug use.

Downloads and Resources

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.