Funding Immigration Courts Should Not be Controversial

Key takeaways:

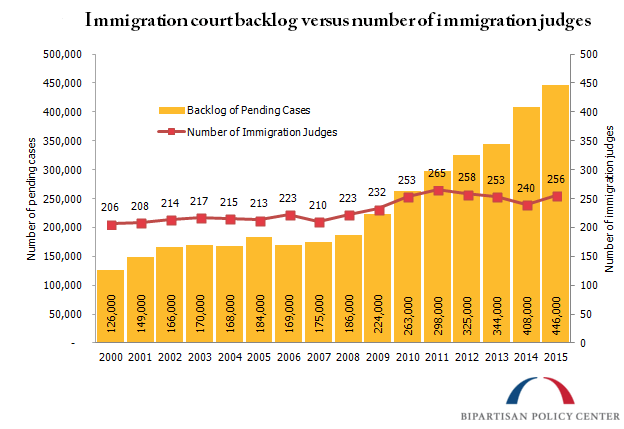

- The backlog of pending cases in immigration courts has grown 160 percent since 2006, but the number of immigration judges has grown by just 15 percent.

- Funding more judges would reduce the backlog, which would allow the enforcement system to function more efficiently and help migrants receive a fairer hearing.

Congress is beginning its annual consideration of federal appropriations bills. As usual, there are plenty of issues to be debated as the committees determine how to prioritize available funding. A controversy over funding for the immigration courts, which are part of the Department of Justice, appears to be developing between House and Senate appropriations subcommittee chairs. For nearly a decade, the immigration court system has been overwhelmed by a backlog of pending cases. Reducing this backlog would not only expedite processing but would also help migrants get a fairer hearing, helping address important concerns from both sides of the aisle. Compared with many immigration policy proposals, funding additional immigration judges should not be controversial.

Since 2006, the backlog in immigration courts increased more than 160 percent, from about 169,000 cases to over 445,000. During that same time, the number of immigration judges has grown by less than 15 percent, and actually declined between 2011 and 2014 (Figure 1). The growing backlog has meant an ever-longer wait before immigrants see their day in court. Last year, the average case took about 500 days to complete, and this year, the average incomplete case has been pending for more than 600 days.

Source: Cases: TRAC. Judges: Department of Justice (personal communication), 2000-2014; Department of Justice, 2015.

The arrival of tens of thousands of Central American migrants last year was a recent driver of the backlog. In May and June 2014 alone, more than 50,000 unaccompanied children and family units arrived at the Southwest Border, representing more than 10 percent of last year’s total number of border apprehensions. More than half of last year’s Southwest Border apprehensions occurred in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley sector, marking the first time any sector accounted for more than half of border apprehensions since at least 1960, the first year data became available. Remarkably, many of these individuals did not attempt to evade detection, but instead turned themselves in to Border Patrol agents based on the misperception that they would be eligible for a “permiso” that would allow them to stay in the United States. The “permiso” rumors were false, but thanks in part to the overwhelmed state of U.S. immigration courts, they had a basis in reality. In practice, many migrants who arrive illegally (in particular minors and families from countries other than Mexico) are given a notice to appear in immigration court and are then released into the country on their own recognizance, or in the case of unaccompanied children, to family sponsors. This situation, at least until the immigrants appear in court date, could feel a lot like a “permiso.”

To address this situation, the administration began detaining more of these migrants. It built three new family detention centers and beefed up the capacity of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in the Department of Health and Human Services, which cares for unaccompanied children who cannot be released to family members in the United States. The administration also placed a higher priority on child migrant and family unit cases in the immigration courts. Immigration courts, which have traditionally had separate dockets for detained and non-detained migrants, were instructed to treat children and family units as priorities alongside those on the detained docket. Unfortunately, this temporary shift of resources did not permanently increase the court system’s overall capacity. New cases for children and families were resolved more quickly, but this pushed other types of unresolved cases further back in line?some until 2019. If the court system is to actually work its way through the backlog, it needs more judges and clerks. Enabling immigration courts to hire more judges would result in the faster removal of individuals without legal grounds to remain.

Funding immigration courts would also help migrants. Although stakeholders raise a wide range of complaints about the current system, adding judges would enable migrants to have their day in court sooner, and give them more time to have their cases heard. Today, immigration judges’ overwhelming schedules can reduce hearing times to as little as seven minutes. On one test of professional burnout, immigration judges were more burnt out than even prison wardens and physicians in busy hospitals. Although stakeholders on both sides of the aisle have raised other concerns about the immigration court system, giving judges adequate time to hear and weigh the facts of a case would likely make the system function better, regardless of what other changes are needed. National Association of Immigration Judges president Dana Lee Marks recommends a ratio of 600 pending cases per immigration judge. The current ratio, 1,750 pending cases per judge, is nearly three times that.

Today’s markup of the House Commerce-Justice-Science appropriations bill gives Congress a chance to bring immigration court resources in line with the current level of work. In light of last summer’s crisis, hedging against future border surges and restoring functionality to the immigration enforcement system should not be controversial.

1 The Obama administration requested an emergency supplemental appropriation in July 2014 to address the influx of migrants, including resources to add 40 immigration judges and teams (https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/07/08/fact-sheet-emergency-supplemental-request-address-increase-child-and-adu). However, Congress ultimately did not pass the legislation.

2 This observation is intuitive, but it is also visible in immigration court data. Between 2014 and 2015, the average number of days to complete a case fell from 500 to 495, but the average number of days a backlogged case had been pending increased from 566 to 603. Resolving some cases faster brought down the average time for completed cases, but putting those cases at the front of the line caused other migrants with unresolved cases to wait even longer.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.