Socially Distanced Voting: How We Can Vote at the Polls This November

When

This event has passed.

Video Transcript

00;00;04;22 [Matthew Weil]: Hi, and welcome to Socially Distanced Voting. We are 63 days away from election day. And with a once a generation pandemic on our hands, I can promise you the November election will be unlike any in recent memory. Hi, I'm Matthew Weil and I'm the director of the Elections Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center. BPC has long been involved in improving voted the voting experience through policy change. That extends back to the 2013 presidential commission on election administration through the BPC task force on elections, which was composed of 21 state and local

00;00;35;25 election officials from across 17 different States. That task force, which got to do much of its work when we were still able to be in person released its report Logical Election Policy in January of this year. Our hope was that this report would lead to policy change over the next several cycles. However, the pandemic has forced many changes to voting this year. As you may have heard for me and many others on this call on the, on this uh,

00;01;03;22 event, there's going to be more absentee voting in November than we've ever seen. And yet we still expect that upwards of 15 million Americans will cast ballots in person in some way this fall - either during early voting or at the polls on election day. And that's what brings us here today. There are many ways to make voting in person work better. I'm going to briefly introduce the members of our event today, the panelists before I do. I want to note that you are able to submit questions either through our YouTube,

00;01;34;06 YouTube channel, our Facebook stream, or you can do it on Twitter #BPCLive. All of our panelists today are incredibly impressive people and have incredibly long biographies.

00;01;47;12 [Matthew Weil]: So I'm not going to read all of them so you can read all of them on their own websites. Uh, Charles Stewart, uh, the third is the Kenan Sahin distinguished professor of political science at MIT, where he has taught since 1985 and as a fellow of the American Academy of arts and sciences. Since 2001, Professor Stewart has been a member of the Caltech MIT bloom technology project, a leading research effort that applies scientific analysis to questions about election technology, administration and reform. In 2017, Professors Stewart established the MIT election data and science lab and 2020 partnering with Professor Nate

00;02;20;13 Persily of Stanford law school & established the Stanford MIT healthy elections project. Juan Gilbert is the Banks, Family, Preeminence Endowed Professor and Chair of the University of Florida Department of Computer and Information Science and Engineering. That is a long title, Dr. Gilbert, he has been working on securing elections for more than a decade, um, including by developing Prime Three, which is the first open source

00;02;45;23 university line design voting system that accommodates both people, uh, voters with disabilities and, uh, and without, and provides a paper print out of the ballot. He is a frequently called upon expert on voting system security, accessibility, and usability for pandemic voting. He is the creator of a ticketing system to help voters maintain social distancing while exercising their right to vote, which we'll talk about today. Gretchen Macht is a, an assistant professor and director of the URI votes group and the sustainable innovative solutions lab at the university of Rhode Island. Dr. Macht’s

00;03;18;20 research on voting has collaborated with Rhode Island, secretary of state, and your votes project was initiated after the 2016 presidential election where a Tuesday recommendations directly cited her as a key expert on shoring future and minimal lines upon places. Her project has created a modeling program for voting this year. And she'll talk about that shortly. And finally, Michael Vu is the San Diego County registrar voters. He's responsible for our lessons administration and the third

00;03;44;29 largest lesson jurisdiction in California and the eighth largest in the country. Michael has previously served as executive director of the board of elections in Cuyahoga County, Ohio and elections manager for Salt Lake County, Utah. He's also an esteem member of BPC’s taskforce on elections with those as brief as I could be introductions, I want to turn, turn to Charles for his presentation, Charles, take it away.

00;04;09;16 [Charles Stewart]: Thanks Matt. And thanks to Matt and all the team at the Bipartisan Policy Center for, um, for hosting this event today, because it's a very important topic. Um, one that hasn't gotten a lot of attention from the press and the public, but I'm sure is something that's been on the mind of the people on everybody on the way on the webinar today. So, um, without further ado, because we want to get to questions and some semblance of a discussion, let me say a few introductory words and then, um, point out some tools that we have, um, posted at the healthy elections site that

00;04;42;26 can help with issues of, um, basically re-engineering elections, um, to manage in person voting during, um, during the pandemic. And I just start, the introductory remarks are just underscore one of the things that Matt said in his introduction, and that is that we expect, um, at least about

00;05;03;19 50 million people to vote in person in, um, in the upcoming election. And we're beginning to see evidence that that's roughly going to be true. That's consistent with the turnout that we've seen in the primaries. It's consistent with the, um, types of, of, um, public opinion research that we've seen. I've just shown up on the screen is probably too small to read, but, but the elections group recently released a report where they reported on voters, reported intentions for how they intend to vote in November. And, um, while, um, is predominantly male balloting is still as

00;05;38;22 consistent with 50 million people voting, voting in person. And of course we have examples like this, a recent executive order, the, um, um, uh, of the governor of Maine, um, restricting in-person polling places in that state to no more than 50 people, um, at any one time. And so we're going to have substantial, um, number of people voting in person and, um, those in person voting places are going to be, um, constraint and, um, people

00;06;07;23 managing, um, officials, uh, managing, um, polling places, um, need a plan.

00;06;11;14 [Charles Stewart]: And that's really the, the theme of my talk and the theme of all of our talks today is, is to help election officials, um, manage. Now I want to begin with, and very briefly remind people. Who've heard me talk before, um, that I like to talk about something I'm now calling, um, the elbow of pain. And this just refers to a graph that many people in, um, queuing theory understand. Sometimes this is also known as the hockey stick graph, where if we graph say we have, um, you know, we have a polling place, we have a couple of, of, of checkin

00;06;43;15 stations. We, um, you know, it takes a certain amount of time to check in. We know that as more and more people arrive say during an hour, during a day, um, actually for most of the day, it doesn't matter how many people are arriving. You don't have any lines, but there comes a point it's about when you reach about 80 to 90% of what the theoretical capacity is that the lines just go through the roof. And, um, this is this elbow pain that we're

00;07;10;04 trying to avoid. Now, one of the things that's going to be happening because of the restrictions of voting in person in COVID is that service times will be longer. It's going to take longer to check in people with, could we take longer to scan ballots is going to be longer to mark ballots.

00;07;24;25 [Charles Stewart]: Um, and, um, so that's, yeah, That's one thing, but then also I'm, as I said before, there's going to be restrictions to how many, maybe how many employing, um, checking stations or, um, voting booths you can have. And so on the consequence is that this elbow pain is going to arrive much, much faster. And, um, it's going to be therefore much more critical, very critical for, um, election officials, at least to avail themselves of planning tools, to check out, kick the tires and make sure that they plan sufficiently. It's not too late now to do that

00;07;56;04 by, by all means what I wanted to point out in just the last couple of minutes here is that if you go to a healthy election site org, which is the website, uh, the Stanford of it, um, healthy elections projects, you will discover a tools section, which has a link to a wide variety of tools for addressing a number of planning, um, topics, including mail ballots, and in-person voting communication, gathering data, data analysis, and the

00;08;23;23 tools are tried and true by and by and large, most were developed before COVID some have been developed for COVID because see, for these groups, they're recognized groups. And many of you in fact have used tools or resources from these groups before. Um, both and Juan are on this list as well. If you go to the section, um, that specifically, um, highlights the tools that we've developed at healthy elections and the Caltech MIT voting technology project, you'll discover, um, a small number of tools that, um, we're

00;08;55;16 hoping that people will take a look at. The one is a very simple tool, which helps you to analyze where the bottleneck is likely to be in your polling place. Is it going to be, um, is, is the limiting factor in your polling place going to be the pole, the voting booth, or is it going to be the check-in station or is it going to be at the scanner? So this is a very simple tool that you can look at. Another tool allows you to, um, take basically known parameters about the number of people you anticipate to

00;09;25;07 show up at a polling place on election day, um, service times and the rest traditional things that have been used in tools like this, but adds a feature, which is the external waiting room, which can be literally another room could be the hole down in the building, or it can be the street and the sidewalk around the corner.

00;09;44;00 [Charles Stewart]: Okay. Limitations. The number of people in, in rooms makes that, um, tool valuable. Here's one that I call the Tammy Patrick tool, cause she's been asking for this for years and basically it, it helps on the election official and answer this question if I have a hundred people at the door, right. When the polls close, how long until that line goes down essentially to zero, is it going to, is it going to take all day or is it going to be in two hours? And that's the type of question that this tool is trying to allow people to look at. And then finally we have

00;10;15;27 the tried and true, um, Steve Graves tool, um, which was developed for the, um, president's commission on election administration. And you can use that as well. Finally, for people who think this is all Hocus Pocus and people who don't know what they're talking about, you can link to two reports, um, um, and an older report, um, and a newer white paper that discusses in lay person's terms, very little math. There is a little bit, but very little math. I'm a lay person's tools about the application of, of queuing theory

00;10;43;10 for managing, um, managing in person voting. So there you have, there's a lot more to talk about, but, um, I encourage you to, um, ask questions here, get in touch with me, um, at MIT. And we're always happy to talk to a local officials and state officials about the application of these tools and the, and the tools of our collaborators. So thanks,

00;11;06;02 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you, Charles I'm next up turn to, uh, Michael Vu, who is our election official representative on this chat. Michael's run elections in several different States, and I'm sure this is a Unique experience for you. So tell us We're doing this year and what you've got to share with our group.

00;11;24;08 [Michael Vu]: Thanks much, Matt, let me just first off by saying, there's no Hocus Pocus when it comes down to this upcoming election that's to be coming to us in a short 64 days here. And it's really not just a short 64 days, but in 35 days, we're going to be sending every one of our registered voters here in San Diego County, a mail ballot. So let me go ahead and go in and straight into my presentation is the practical side of all of this and how is it going to come all together for us here in San Diego County. But before I do that, let me just talk about what the pandemic means for us and kind of

00;11;55;17 step back a little bit and show you some data as it relates to San Diego County. Now, as we were approaching the March election, this is the data that you should see here is that the pandemic has affected us primarily in two respective ways. Normally, as we are, we're anticipating conducting this upcoming election, we would have approximately 1600 neighborhood precincts, as well as approximately 9,000 volunteer poll workers that we would need to recruit to prepare for the election.

00;12;21;11 [Michael Vu]: But as we saw from the pandemic is, is that as we looked at our data from the March election where we have 1,548 precinct, you can see here is, is that we have major impacts. And when it comes down to uncertainty, uncertainty, and the total number of all workers that we could recruit, as well as the respect of polling location, as you can see here is, is that when it comes down to our poll workers, 65 plus age group, 30% of all poll workers that serve for us in the last election, the March 3rd presidential primary election, we're in this high risk category

00;12;54;10 of 65 plus age group, but it just doesn't stop there. If you look at the other side of the spectrum, we have a number of folks that serve as a poll worker who fall within the 16 to 19-year olds, um, our high school poll worker program. And normally we have approximately anywhere from 1500 to 2000 of those individuals to serve in some capacity for us, but those individuals now are distance learning from home. And so we have been greatly impacted with our

00;13;20;08 ability to conduct a neighborhood polling place. And as we can see there is that of the 1,548 precincts that we had into during the March 3rd election. We had 60 over 60%, nearly 70% of our polling places reporting to a private facility, whether that's a neighborhood garage and at least in California, where it's nice and sunny, that you can actually use a garage, um, two pizza parlors and just, uh, various small businesses. But we know that those may not be suitable any longer for social distancing, uh,

00;13;50;14 requirements. Um, as well as the uncertainty of use, we saw, uh, although we didn't have to really get through the election under the cloud of a primary election under the cloud of the pandemic.

00;14;02;04 [Michael Vu]: Well, what we did see is a number of our colleagues, uh, from across the entire country where they had to conduct an election under the pandemic and saw a couple of private facilities that were effectively pulled underneath them and their ability to conduct the election and created potentially voter confusion. Here, we needed certainty. Certainty is our bread and butter. When it comes down to elections, all, most of those who are listening and are, uh, elections administrators like myself, know that we are an event driven organization that meets certainty and all that we do and need years, if not months and

00;14;34;22 years to plan out for an election that we're going to have. So let me go to what the California has done. As you can see there in the purple a hundred percent of the governor has issued two executive orders, all registered voters, all active registered voters will be receiving a mail ballot. And this coming election, he provided a third option to the existing law, which is option number two there in purple, and then made voter education a requirement across the entire board. There's always been voter education, a

00;15;02;25 requirement, but much more robust in March. As you can see there is, is that we conduct an election in a neighborhood polling place at format. Um, and with 1,548 precincts, nearly 9,000 poor workers needed to be recruited. We had approximately a 62 mail ballot drop off locations that we had over across a seven day period. Um, and then as you can see in the blue we have now, what we're going into the election since our world has, for the most

00;15;29;25 part been up ended. Um, we have changed our entire model, something that we took for maybe since the last presidential, uh, presidential general election to conduct. We're now four-year period.

00;15;41;22 [Michael Vu]: We're trying to change the model on 1.8, 4 million registered voters in less than four months. And as you can see here, this means that there has to be a major campaign, robust campaign to notify every single one of our registered voters here in the County. Uh, what we're going to plan on doing is consolidate more heavily. All of our precincts into super polls is what we're calling it at 235 of them, much larger facilities, 2000 square feet in space. I'm open for a four-day period as opposed to a one day period to really distribute out voters

00;16;14;27 across those four days. Um, on top of sending them on a mail ballot, that's going to be out there. Voters will still be assigned a polling location as opposed to needing 9,000 volunteer poll workers. What we will need is, is approximately three and a half thousand, uh, poll workers that are out there. And it's no longer really a volunteer because we're going to be paying every single one of our coworkers, an hourly stipend, anywhere from $14 and 25 cents to $18 per hour. In certain cases, we'll have a site manager

00;16;42;29 that's going to be paid a $20 per hour. And then we're going to double the amount of mail ballot dropoff locations and quadruple the amount of time that we will have in the upcoming election. And then we're launching into the most robust election campaign that we will have ever conducted here in San Diego County to inform every single registered voter that's out there. And so I want to show you what our priorities and goals are effectively. There's two things, how do we balance and prioritize everything you know

00;17;11;18 about elections, office, integrity, accuracy, transparency, security, all of, and then coupling it with providing a healthy and safe environment.

00;17;19;25 [Michael Vu]: And then bottom line is to inform all of our registered voters here about fewer locations running for longer period of time. Uh, as well as that every single registered voter is going to be receiving a ballot. And then finally, I want to show you our mailer, that we're going to be sending out, that we have sent out to every single registered voter within our County to give a primmer of what this election is going to put that verify your residence address and mailing address, to make sure that there's no delay in your ballot, valid getting to also do a level of list maintenance as well prior to sending out the mail ballots.

00;17;51;06 And then what you see here is effectively what our polling place layout is going to look like a on whole, we're going to have approximately 8,000 voters going to each location, a 2000 square feet. As I mentioned, 15 poll workers, as opposed to our normal for poll workers and then seven electronic poll books to assist in the workflow of the voter flow to get voters through the process much more quickly. And then upwards of 23 voting booths, that's a voting booths as well as seven ballot

00;18;19;03 marketing devices on average, and then our roads safer San Diego logo. This is effectively what our campaign revolves around is our votes safer San Diego, uh, in, in the County, not only by voting your mail ballot is what we're impressed upon voters as part of the safer way of socially distance. Uh, but also, uh, to get the word out there about how this election is impacting them. With that I'll turn it back to Matt.

00;18;48;00 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you, Michael. And I have some questions for you. I want to encourage everyone to make sure that as you have questions that are popping into your head, like I do, I miss you, you put them in the chat and YouTube on Facebook or on Twitter using #BPCLive, uh, Dr. Gilbert, I'm going to turn to you now.

00;19;06;13 [Juan Gilbert]: Okay. Thank you, Matt. And thanks everyone for tuning in, um, what I've worked on begins with an observation which was with COVID and this pandemic, I watched the primaries in particular Wisconsin, where there were long lines for me and people were concerned about their health. And later we found out there were people who actually became sick as a result of going to vote. And so I came up with this idea

00;19;37;21 on how to allow people, if they had to vote in person, how do you mitigate and navigate that arena where I got to vote in person? And if there's a line, what, what am I supposed to do? So I came up with this idea it's called inline ticketing. So I walk you through the scenario of how it actually works. So the poll workers. So they'll go to, uh, use Michael as an example. So let's say San Diego has a, one of those locations

00;20;05;09 and a line is starting to form. But before that election began, Michael's staff went out and they purchased a, a computer or a laptop, a printer, and a QR code scanner. And then they downloaded this inline ticketing software, which I'll come back to. And if a line is starting to form what Michael's staff would do is they would look not necessarily at how long the line is, but they want to get a measure of time of how long it takes a person to

00;20;35;12 lead the voting area or enter the voting area.

00;20;38;08 [Juan Gilbert]: And the other words, what's the amount of time the line moves by one. And that average amount of time let's say is a, I don't know, five minutes. So what happens is, as the line is forming, the poll workers would say, look, there's 20 people in line. Uh, average time of, of waiting is going to be five minutes, give me 20 tickets. And what the system would do is print out 20 tickets in English and Spanish with a QR code that says, please return at a particular time. And it tells you that

00;21;13;02 this ticket will expire at a certain time, as well as specified by the poll worker. So they may have a 10 minute window to come back. So then you take these tickets and you hand them out in the order of the people in line. So what is this doing? Well, essentially, we're creating a virtual line. You're holding your spot in line. So now you can take your ticket and walk away. I like what Michael was showing, where you can have. I mean, uh, what

00;21;40;11 Charles was showing where you could have separate rooms, so people could go to another room. They could spread out. Uh, they don't have to stand in line next to someone and they disperse. They come back at their time, you scan it. It says, good. You're back on time. Then at that point, you verify the person's identity or however you verify them, the vote, and then they go vote. And again, this software is free. I created it to run on Mac and

00;22;07;20 Windows, and the goal is to empower people like what Charles was saying with the healthy elections project, empower people to have tools at their fingertips, that they can utilize to have confidence in their vote to plan their vote and to do it safely. And you can go to inline ticketing.com, inline ticketing.com, and you could read it, see a demo and, and download

00;22;35;20 and use this software, uh, again is free. So that's my contribution to try and help keep people safe at voting in person this November.

00;22;49;30 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you, Professor Gilbert. It's very interesting. And I'm going to have more questions for you as well. Um, Professor Macht is going to talk about, um, her program been a big fan of Yours for a long time, how you are doing line management, obviously, because she's been involved with line management and Charles before, but we love your program and want to hear about what you're thinking when it comes to pandemic voting.

00;23;12;15 [Gretchen Macht]: Sure. Thank you very much, Matt. So if we could bring up the presentation here, I wanted to share with you a little bit about what we are looking at with respect to layout and what that means in voting facilities, as well as flow. So if we go to the next slide, please, We look at socially distance equipment. So if we're looking at how to plan the layout of an in person voting location, not only do we have to consider

00;23;44;21 where people are standing so that they feel comfortable in their own space. So the two foot by two foot voter space, but if socially distance ring, that starts from the edge of that space, that is six feet. So you can see that by the pale red ring. And then once you have somebody who's standing in that voter space, then we're concerned about where they are standing. So how does that look in with respect to, um, a ballot marking device or a

00;24;14;23 voting booth or an optical scanner, or how that looks with respect to checking in and how that overlays with somebody else's socially distanced ring at check-in. Then we have a voting path. So how does that work? When we are passing one another, who are either checking in or actively voting and they are trying to exit the system. So the three foot voting path. So next side piece. So when we look at the adjusted space requirements, if we

00;24;46;00 are trying to understand how to reasonably fit five privacy booths that originally, or traditionally only took up 208 square feet. But when we start assuming the socially distance six foot from the corner of each voter space of a two foot by two foot space, that's included, then what ends up happening is a much larger space. That's almost five times the space. Next

00;25;08;27 slide please.

00;25;13;20 [Gretchen Macht]: So if we start with one click, we can see that there is a section one click, please. Great, And a second click. And then we can start to see that if we take the original layout and the original square footage that we had for those five voting booths, and we are overlaying them on our new space, we can have a, uh, three more clicks, please. We can see that it is literally a little

00;25;42;23 slightly more than five times the amount of square feet for the same type of equipment. So if we go to the next slide, please. So when we want to consider the space requirements for an entire in person voting location, let's just look at eight voting booths, maybe two check-in stations, um, when, uh, accessible check in location, a ballot box, and let's say the sanitization area, which is valuable and very important now in 2020, more

00;26;14;15 than ever. And then two chairs for observers, what does that type of square foot look like? And this is where we can have the same amount of equipment, but we can have very different amount of square footage. Especially when we start looking at where we are putting things, what are we allowing in terms of overlap? So you can see our socially distance circles and where they are overlapped based on those locations, as well as the unit directional flow of the space

00;26;43;03 change, um, where people enter and exit a system, but we can sure as hope, try to plan it so that eighth and as comfortable as possible. And please note that we are not assuming, um, partitions or plastic or acrylic panels. We are simply just trying to look at it with, if we only have the ability to take this equipment and put it in a location, this is what we are able to work with. So if we can go to the next slide, please.

00;27;08;01 [Gretchen Macht]: So we have a few various examples here, so a very straightforward pulling location, or this is an elementary school gym. So we have on top the plan view, and on the bottom, we have the 3D view and we can see that even with the traditional layout and the socially distance layout, we have two check-ins in both locations, and that is quite successful when we get to voting boosts, we only minimize about, um, we don't actually minimize at all. Oh yes. I loved my team. What they were able to do is reassess the layout and actually fit two additional, uh,

00;27;42;12 voting boosts in the same square footage, just based on taking that and rearranging where we can assign, check in and check out. So the next click, please. And then we have really challenging locations such as the city hall, where you have chairs that you are unable to remove. And I know that sometimes, you know, we have thought about going in and removing them ourselves, but we know we are unable to do so, but we still

00;28;08;02 have to figure out what it means to put those two voting booths on the socially distance side of that city hall and what that means in terms of layout and what that means in terms of the unidirectional paths. So still having everyone walk around those seats that we would prefer to move, but even then we started able to fit a single checkin. And we only reduced the voting boost by two, which is quite successful, especially given such a

00;28;35;13 restricted location in the next place. The next one is a much larger location. This is an auditorium where you can literally go and play basketball. This is at a local community center. There's a stage up there that you can, this is probably around the corner for some of you or some of you have some of these super locations that you're considering.

00;28;54;04 [Gretchen Macht]: We are able to fit, you know, eight location, eight check-ins at that location. However, we significantly had to reduce the ballot, marking devices by a third in order to fit it in that space and still have unidirectional paths because this original station was established based on having bi-directional paths. Voters could go where they wanted and they could exit the way that they wanted and they could exit whatever door they wanted. However, with the restrictions that we have that are unprecedented, as I'm sure you are all very aware that did reduce

00;29;27;11 the ballot, marking devices by a third it's the next place we have a library. So this is where we, the space did become even those as a medium sized space. And a lot of us are concerned about the cozy spaces or the super large spaces in terms of dynamics and lay out this as even a medium sized location. We did have to significantly reduce the number of check-ins as well as the ballot marking devices in this location from 20 to five. So

00;29;55;12 that's a Quarter that's Much smaller. So then the last one is a fire Station next, please. And as a fire hall, it's definitely a cozy location. It's one where you definitely, you know, you go to the people next door, you know, your poll workers. You've seen them there for a very long time. We still can work within that space that we have the same check-ins, but we have a minimum we

00;30;21;30 do reduce by one particular voting booth. So what this means is that when we consider layout, not everything needs to be tight. Not everything needs to have plastic if you can't afford plastic, but there are ways to look at the layout that is valuable and important. And if we go to the next two clicks, please, I want to show you how we looked at a Rhode Island case study, where we helped them set up for the 20, 20 presidential preference primaries in June. And we were able to look at the general COVID layout

00;30;54;07 diagram, which you can see off to the one side and the 2D but floor plan layout.

00;30;59;12 [Gretchen Macht]: And then what that looks like when you have workers who are setting up that location in the 3d layout. So we wanted to also maintain social distancing, of course, but also the flow management. We do realize that there was potentially a reduced capacity. We wanted to look at line control and what that meant as well as staffing is reduced and then equipment sanitization. So next slide please. And then if you could click one more please. So this is a quick video of when we start understanding what it means beyond my out, and we start learning in terms of flow of

00;31;31;06 people, and please excuse the fact that this program would not let me add, um, masks. So, um, it just let's assume that everybody is indeed wearing masks because I hope that everybody would, um, as we all hope as well. And I just wanted to show that we do have the ability of when we have complex systems to understand what that means in terms of timing, what that means in terms of flow, what that means in terms of not just the layout, but the integration of layout and flow as in to outside of the system or inside of

00;32;00;18 the system. And next slide please. So we ran this computationally for all of the 40 plus locations. Next slide, please. We ran this for all 40 plus locations for the entire state of Rhode Island. And what we were looking at is how many minimum poll check-ins, how many voting glues, how many scanners, how many workers, and then Rhode Island is quite special for certain elections where we have a

00;32;28;26 disaffiliation location. So, um, after you've voted in your primary, then you choose to no longer be a party affiliated, or you switch your party affiliation. So we had that additional station in there as well. And what we're able to see here is that we have the minimum shown in the blue and we have in the red, the maximum values. So we can see that even in running this type of optimum size kind of system, we have a maximum average queue of 30 or a minimum of one. So there is high variability here. We also do

00;32;59;29 have a maximum exposure in certain locations that exceed 60%.

00;33;03;24 [Gretchen Macht]: We have nine locations where voters can, um, where workers can have a, an exposure to this level. So wanting to look at how that impacts workers, because if that is a 12 hour election day, that it does mean that they are cleaning over nine hours of that day. So what does that mean? So these are the types of things that when we start taking the visual simulation, as well as the layout, we can start understanding what this means in terms of those responses that we can plan for. So next slide,

00;33;34;21 I think it's two clicks. Next slide please. So these tools are available at URI votes. You can go and try a free trial for a SketchUp. You can also sign up for a monthly subscription if you choose. I do not get any profits of it. So do what you will, but we did provide all of these things and all of these example layouts and all of the equipment on the 3d warehouses SketchUp. So you can download it into your own system and software. And, um, we do have a visual

00;34;05;13 model where you can create your own video of your own voting location, that you want to test out a layout and want to see how it functions in terms of lines, as well as average time and system and maximum time and system. So thank you very much, and I really appreciate your time and I love really look forward to the discussion.

00;34;26;10 [Matthew Weil]: Okay. Thank you. That was great. I'm just gonna ask a few starter questions again. I'll, I'll ask That anyone who is, um, viewing this session, you can ask your questions in a YouTube chat, Facebook chat, or on Twitter, #BPCLive. Gretchen. I want to stay with you for a second while it's kind of fresh in everyone's mind To start off, but what is the ideal polling place? What is the best point in place to design? What would be the parameters and how likely do we see those kind of pawn places around the country?

00;34;56;29 [Gretchen Macht]: Oh way to give me a soft one. Um, honestly, it's ones that you're the most familiar with. It's the ones that you understand that, you know, how that pattern exists. You know, what the arrival pattern is like, you've worked with those locations, you've worked with the people who run those locations and you have a relationship with them. When you start working with new locations, that presents more challenges. I would encourage everyone who's planning for various sizes of locations to not

00;35;26;08 only consider the cozy ones, as well as the super dupers extra, extra large locations, but do pay attention to the middle sized ones. As we did see from those examples that that could provide a challenge. So I would encourage you if you have the opportunity to use ones that you have previously used, go for it. And if you have new ones work with those who know that location, the best.

00;35;51;14 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you. And Mike, I'm going to turn to you for a second, because you were talking about how you went from 1,548 neighborhood polling places to 248 what you're calling the super precincts. Um, what's unique about that is that a lot of other States that have been making these, these big changes to consolidate their polling places have moved to vote centers where anybody in the jurisdiction can go. And that's not the case where you are. So how did you come to that decision and what are the implications of it?

00;36;19;21 [Michael Vu]: Well, ultimately the decision was based off of the pandemic. I mean, all of this that we're doing is, is in response to the pandemic. The fact that as it demonstrated and showed is that 30% of our population is of our poor worker population is impacted in this high risk population of 65 plus age group. Plus the fact that students were also a distance learning from home. And so that ultimately we had to change, uh, the legislature as well as the governor gave us this additional option. And again, it's not necessarily the vote center model in that there's a big

00;36;50;18 difference here, and that is voters are still going to be assigned to a specific super pole to go to. And we're just consolidating voters to a specific site. Um, but you got to put this all in context here is that in San Diego County, particularly in California, but in, in, in, in San Diego, 76.5% of our electorate is already a permanent mail ballot voter that is they've already signed up and requested a mail ballot to be sent to them.

00;37;16;29 [Michael Vu]: Anytime there is an election that pertains to them, it's going to be had. And so for us, uh, really this, the, the, the sending everyone a mail ballot is really not going to be a big shift for us because we have invested time and infrastructure be able to handle something like that. It's really these two proposed locations. That's got me really worried because you don't change this on a dime, but like this during the biggest presidential election that we're going to have in a four-year cycle and potentially in the history of San Diego County. Um, let me just answer

00;37;48;28 the question that, uh, that you had asked earlier for us, our ideal was no less than 2000 square feet. Transportation corridors has to be considered. Public facilities was a must have now private facilities, but public facilities, because once we were able to, uh, secure them, they're secure for the life of the election, as well as the timeframe that we need to not just for one day, but upwards of a six day period of, of getting these active sites. And of course, we're looking for open layouts, nothing that we have to

00;38;17;09 worry about, chairs, gymnasium, so recreation centers, community centers, school, multipurpose rooms, and cafeterias, all of our school districts and their superintendents have really come together as a community for us to be able to identify these respective locations and secure them and be able to use them on election day. But it remains to be seen the biggest unknown as well as uncertainty is voters. How will voters behave on election day? Will they vote their mail ballot in the high numbers that we need them to, to

00;38;45;09 really not spread the, the, the, the virus if they go to their respective locations. But certainly the legislature has stepped in by allowing these locations to be open for a four day period on top of all the other 125 locations that we're going to have for a mailbox drop off locations, as well as the 235 Superbowl sites that we're going to have.

00;39;07;26 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you for that. Charles, I wanted to talk about the elbow of pen because you can't put elbow pain into a slide and not expect that you're going to get a question about it. Uh, so you talked about the theoretical capacity of polling places and how it's going to shift leftward, uh, this time, how are election officials supposed to know what their theoretical capacity is for every point place? Um, and also, can you speak a little bit about why bottlenecks happen at different spots in the process? Not just checking, I'm sorry. Um, I was focused so much on the

00;40;00;17 second question that I forgot what the first question, it was more about, um, how, uh, election officials should know what their new theoretical

00;40;10;24 capacity limits are for every polling place or road center that they're going to use it, as you noted in your presentation, it's Type of a shift leftward. So why that is how they could know about it. Um, and also why bottlenecks appear at different places.

00;40;24;18 [Charles Stewart]: Yeah, well, you know, these bottlenecks appear for a variety of reasons, but, um, and, and sometimes they appear because, um, you've had emergencies, et cetera, but you know, the, the types of tools that we're talking about here, and I think Gretchen's tool is as well is based on what I like to call the physics of voting. And that is to say that there are certain, there are certain mathematical regularities that, um, are used in Walmart or were used in call centers, or even using the design of, of, um, computer chips. And, um, and this gets to the, you know, kind

00;40;59;13 of study what happens when systems become congested. And so there are, you know, three big parameters. Um, how fast do people arrive?

00;41;06;29 [Charles Stewart]: Um, how long does it take to serve people and, um, how many places can you serve them? Okay. And there's all sorts of analogs in the, um, in, in voting. And so what I hope, um, if people are inclined to look at our, the, the, um, the tools that I highlighted in my presentation, they're set up, um, both to play around with these parameters on the web. And if you find that it's useful, you can actually download

00;41;36;24 Excel spreadsheets and do an analysis, say for an entire County, um, all of this really works best when you know, the parameters that we're talking about. And that is to say, you really need to know how long it takes for a typical person to check in. And if you don't know that, and you haven't gathered that data before, you probably need to do some simulations, maybe

00;42;03;25 even some play acting to try to get some reasonable numbers. Likewise had people play act in filling out balance. If you haven't timed it before, and then go to the, you know, then go to the, um, the tools that I highlighted and plug in the numbers and see, um, what it tells you in terms of an average wait time. Um, the, the, the new, um, the new, um, tools are actually optimized for thinking about the restrictions that

00;42;35;21 you're going to face during the pandemic. For instance, you can enter in, let's say that you've kind of, you have a sense about what it was in the olden days, that you had a sense about how long it took to check somebody in and how many people you thought would, um, show up at a polling place, for instance, and you could enter in all that kind of normal time data. Then we have, um, boxes where you can play around in the following way you can play.

00;43;02;25 [Charles Stewart]: What if analysis? What if turnout is only half of what we've seen in the, what if we can only have six rather than 12, um, polling, Booz? What if it takes three minutes to check somebody in versus two minutes? So you can play that, what that, what if analysis and I, you know, it really, you need to know what your numbers are. If you don't know what the numbers are, even without, even without a pandemic or you're, you're going to be potentially in trouble, but even making estimated

00;43;33;26 guesses, um, and playing with these tools can give you a sense about what the dynamics are. Um, and then finally, just the last question that Matt, Matt raised, which is related to the, to the first one, you get, you get bottlenecks because, um, um, the service times are too long, or you don't have enough, um, service, um, you know, systems like check-ins or too many people are arriving. I mean, it's that simple. And, um, what we're trying to do

00;44;02;05 right now is work on all with all of those parameters. I think the caution here is this, and it really shows up in Gretchen's presentation. A lot of folks are thinking, well, you know, I'm only going to have half the voters vote in person that I normally do. And so it's okay for me to cut the number of voting booths or cut the number of checking stations in half, or consolidate all the polling places down, down, down into half. And that's

00;44;30;10 really dangerous unless you do some sort of simulation of any sort of sophistication and ease. Um, because one of the things I've learned, I mean, Gretchen's a real industrial engineer. I just play one on television, but one of the things I've learned is in the last several years is that your intuition can really, um, do you in, and you need to need to work with these tools and understand, um, how things can go bad really fast.

00;45;01;03 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you, Charles. I know we're getting some good questions now, and I want to just turn to Professor Gilbert. One was one last question before I open it up to the, uh, the audience. Professor Gilbert, your, your plan for the ticketing system is pretty novel. Uh, I don't know that a lot of jurisdictions are doing that now. So what are the barriers that you're seeing to getting that stood up in time for this fall?

00;45;25;10 [Juan Gilbert]: I put it out there for election officials to use, and I think there's this fear of, I don't want to do anything else between now and the election. I'm really afraid of adding or doing anything different. And I understand that, and I think this is why I designed it the way I did to make it very easy to use. Uh, it's not designed for someone that, uh, like myself, who's a computer scientist is designed for the poll

00;45;54;22 workers. They said design and the easy way to use and to implement. And so the, to me, the biggest barrier is Just getting over the hurdle of, if I have to do this, how much more time would it take? How much effort would it take to put something like this in place? And I would say we can minimize that and I'm happy to have conversations With people or how they prepare for something like inline ticketing.

00;46;20;16 [Matthew Weil]: I appreciate that. I appreciate that. I do want to turn to some of the questions, some I'll point of point in the direction of Michael as our resident election official on the panel. Um, so the first one comes from, uh, Phillip who's watching us on the YouTube stream. Um, Phillip was asking, how are we addressing

00;46;39;10 [Matthew Weil]: The needs of voters with disabilities? who are unable to make it to a polling place, but also unable to use mailed ballots.

00;46;47;16 [Michael Vu]: Well, for the state of California, we had to introduce for the very first time in the March presidential primary election, a system called a remote accessible vote by mail system. Uh, it was really, uh, for individuals, uh, people with disabilities, as well as our military and overseas voters. And it was introduced for the very first time across the entire state. It certainly, it was the first time introduced here in Andy, the County. But in fact, effectively what that system allows is us the ability to send a ballot via email to the voter.

00;47;22;20 It's essentially a link that they were, would be able to mark onscreen and as opposed to online, I want to be and make sure that that's clear it's onscreen. They would then be able to print it out and then send it back to our respective office. So we could, um, again, this was born out of frankly, a lawsuit that came up, uh, during, uh, one of the smaller, uh,

00;47;46;17 elections that a County had conducted. And ultimately the state legislature passed this remote assessable vote by mail system, also known as RABBM.

00;47;58;19 [Matthew Weil]: Thank you. Uh, the question from Steven Rosenfeld was asking about, um, how, where drop boxes are placed are affecting in person voter traffic. So this might be a better question for Charles and Gretchen. Have you seen any research to that effect?

00;48;16;17 [Charles Stewart]: Um, I'll just start in saying that I actually haven't seen, I haven't seen the research on that effect. I will though use this as an opportunity to, um, highlight another tool on our website, um, which was developed by Mindy Romero at university of Southern California, which is a tool for the placement of, of drop boxes. And, um, so there are tools out there for the management of, of all sorts of, I mean, just the location of, of in-person voting, whether it be an in person, um,

00;48;47;04 polling place or a, um, or a Dropbox. Um, but I don't know about on the research, maybe Gretchen Gretchen does

00;48;53;18 [Gretchen Macht]: No, I haven't seen anything that overlays that, but I do echo your comment on Mindy Ramero's work. It's fantastic.

00;49;02;06 [Matthew Weil]: So maybe I'll turn it to Michael. I mean, it has how certainly California has had drop boxes, um, for a while. Um, how does their placement affect where you put polling places either during the normal election or, uh, during this pandemic collection?

00;49;18;00 [Michael Vu]: Well, let me just really speak for, for San Diego County, as we're doubling the total number of mailbox drop off locations for us, it's not so much as boxes for us in San Diego County. We've always had staffed locations. And were there places, frankly, in strategic locations, again, locations that are known within the community for us, that's all of our County libraries. And now for this upcoming election, it's all of the city libraries we're using YMCAs that are out there. But the reason, one of the reasons why we use staffed, uh, uh, drop off

00;49;50;24 locations is just because it does a couple of things for us. First of all, voters in San Diego County are more comfortable to handing over their ballot to a trusted source and a trusted source is our office and our staff. The second portion of it is it allows us to cure it on the spot, any issues with that voters ballot, their mail ballot, that is if they fail to sign, we have the ability to now have them show the back of the envelope to one of our staff members to then our staff members showing them, letting

00;50;18;21 them know that they have failed to sign.

00;50;20;07 [Michael Vu]: So it corrects it there on the spot. So we can actually count that mail ballot, but it does a variety of different things. But yes, as, as, as professor Charles, as well as, uh, talked about his, is that Mindy, uh, Professor Mindy Romero's, uh, tool is a great he's. She's now expanded it to all of those other counties that are not running it, a boat center model, and similar to the, for us in San Diego County, the ability to use that now we're kind of really far deep into the election cycle right now to be able to use the tool, but we having a, some guidance

00;50;50;21 for the public commenting period that we're actually in right now of determining whether or not a site should be moved or not be moved, whether that's a mail ballot drop off location, or one of our super poles location. So that period is open as we've publicly noticed for the voters in San Diego County, the sites that we're gonna use for both 125, a mailbox drop applications, and the 235 super polling locations.

00;51;17;23 [Matthew Weil]: So I'm seeing a question from, uh, Jolene McNeil. Uh, I think it's probably in reference to the fact that a lot of what we've talked about right now is that building a person is going to be a little different, maybe a little more difficult to administer and to experience. And so it should election officials, and this can go to anybody, um, be discouraging people from voting a person, uh, and in favor of voting more through a mail ballot. Who wants to take that one? I'm going to get to our election official. Mike, I'm gonna put you on the spot.

00;51;44;07 [Michael Vu]: Let me go ahead, start that for us. Yes, it is. Because if we really think about the pandemic itself, we've got to make sure that we're balancing out the priorities of an election, which we know this is going to be a big election. We know that the turnout is as good as any imagination of where we're at right now. We're expecting 1.4 to 1.5 million individuals to cast about on this election. So for us is how do we get voters to vote that mailed out that we're going to send every single registered voter here in this County, as well as in the seat. So for us to

00;52;17;11 send a person, if a person wants to vote at a, at a only location and in-person location, that's totally fine. What we're asking them though, is, is use it as an alternative to voting that mail ballot. What are those respective reasons why it's because you didn't receive your mail ballot and it's too late to receive a one now through the us postal service, because you mis-mark your ballot in error. And so you need a remote placement mail ballot for here, us in San Diego County, it's individuals that failed to register on time. And so they need

00;52;45;02 to exercise their same day registration opportunities, which is registering and voting, uh, at a specific site, uh, within the four day period, uh, that they're going to be re uh, open, um, or because you just demand at one that voting experience at the in person, cause it is tradition and it's okay to do any of those respective case. All we're trying to do is distribute those voters as well as provide the workflow and all the necessary personal protective equipment that is going to need to be

00;53;13;26 installed and used appropriately if facilitate a healthy and safe environment. So there's no necessarily deterrence, but again, the deterrence is one thing. It's the pandemic. We've got to make sure that we're not creating crowds of people trying to vote and exercise their fundamental right.

00;53;33;10 [Charles Stewart]: Um, if I could just jump in really quickly. I mean, another answer to that is that, um, it may actually be too late to convince voters to do much of anything. What we're discovering in public opinion, polling is that voters are actually beginning to make up their minds now about what they want to do. And so, um, I, I think it's important to continue to message about what the risks are, the opportunities, et cetera. Um, but voters are kind of making up their, their minds based on what they want to do, not, and oftentimes not based on what the laws are or the convenience and those sorts of things would put someone like Michael in a

00;54;04;25 really difficult spot because he has to be prepared for a lot of in person. I mean, basically over prepare for in-person voting and over-prepare for mail ballot, um, in order to make it work. Um, but that's the world we live in right now.

00;54;17;25 [Michael Vu]: I always call it the belt, suspenders, staple gun approach,

00;54;23;19 [Matthew Weil]: Something will work. Um, thank you for those answers. I want to end with one, one question, uh, and maybe it's the most hot button question that we can have for, in person voting in the fall and coming it's coming from Linda Santi. Uh, and it's mostly about masks and masks mandates at the polls. I know this Gretchen mentioned it in her simulation. She didn't have the masks you, unless she definitely advocates for it. Um, how can we keep both coworkers, other voters safe? Um, if masks are going to be mandated, um, are there design ways of doing that? Um,

00;54;56;29 either different rooms, different areas of rooms, uh, what, what are you seeing and what you've been able to, um, to research Gretchen and Charles specifically?

00;55;06;27 [Gretchen Macht]: So if you are not, if you are not going to mandate a mass squaring, there are certain things that you need to consider such as, um, PPE of course, for the workers. Um, also how you clean and what your cleaning mandate is of the equipment, but also ventilation. And the way that that insight voting location is laid out with respect to that, there is some fantastic work that's happening through ASHRAE. That is trying to

00;55;36;21 look at the sizes of locations and the square footage of those locations and what you need to consider as a healthy volume of people in a particular space, also based on the ventilation equipment in that. So it does take it to a whole new level of things that people need to consider when setting up those locations. I've also seen it where, um, there has been masked mandates and I have gone and done some observations. And while, um, COVID

00;56;05;23 mandates and masking is required in certain locations, and most people walk up and they start, Oh, I forgot my mask. And then they go back and they get it out of their car and then they come back and then they vote. So I think it's all about what the community is mandating and, but there is fantastic work about ventilations and in person locations through ASHRAE

00;56;29;07 [Charles Stewart]: Yeah. If I, if I can just add, I mean the thing that's impressing me is, is that local election officials are doing their best, um, to design in person polling places, almost as if they're assuming nobody's wearing a mask. And I mean, I'm just really on, on Gretchen's software. Um, um, so thing, number one is that by doing the social distancing and all the rest, it's possible to engineer a site, in which, as I understand it, read the literature, you actually would be minimizing the risk to the poll workers and to the voters, if, if a large

00;57;01;27 number of people don't wear a mass cause. And if a couple of people don't then, um, I mean, it, it may not be such a big deal, still wear a mask in the polling place.

00;57;14;00 [Michael Vu]: Can I just add one more point to that whole picture, matt, just really quickly, we're working with our public health of officers. So we've got two of them, uh, that we're working with closely with. I was on a two hour call and one out of the two hours was all about just gloves alone on the donning & doffing of gloves and Whether or not voters should use it, but for here in San Diego County, as well as the entire state mass are not necessarily going to be required, although we will supply them that. But if a voter comes without a mask inside San Diego County, we're going to have them vote outside or by

00;57;44;25 curbside as well. So that's how we're going to tackle the issue of a person coming in without a mask.

00;57;51;19 [Matthew Weil]: I imagine that your solution also would work for that situation as well. I mean, put them in a separate area and you can call them back into the virtual line.

00;57;59;00 [Juan Gilbert]: Exactly. Exactly. Well, I can't, I can't sum it up better than that. Exactly. So thank you all for joining us. Thank you to the panelists for joining me today. Thank you for all of our viewers. I want to remind you that you can subscribe to BPC's YouTube page and you can get notifications for more election events, which we'll be having through the fall, but also all of the BPC's good offerings. Uh, and thank you for joining us today.

Share

More than 50 million Americans are expected to cast their November ballots in person this election. The debate over expanding by-mail voting options has overshadowed the fact that state and local election officials must also adapt to provide socially distant and safe voting opportunities at the polls.

Please join the Bipartisan Policy Center and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab for a discussion of logistical issues, resource allocation, and ways to make in-person voting work in the midst of a pandemic.

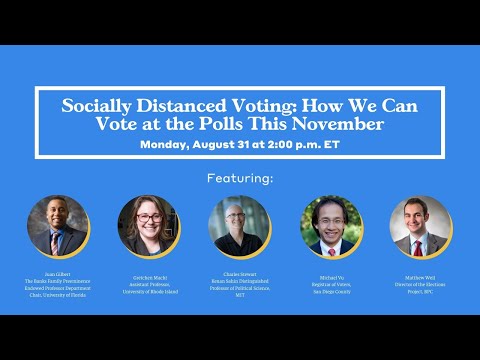

Featured Participants:

Juan Gilbert

The Banks Family Preeminence Endowed Professor Department Chair, University of Florida

Gretchen Macht

Assistant Professor, University of Rhode Island

Charles Stewart

Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Political Science, MIT

Michael Vu

Registrar of Voters, San Diego County

Moderated by:

Matthew Weil

Director of the Elections Project, BPC

In light of restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, BPC events have shifted to all remote formats, such as video teleconferences or calls.

More Upcoming Events

Sign Up for Event Updates

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.

BPC Policy Areas

About BPC

Our Location

Washington, DC 20005