Agricultural Soils as a Climate Solution

When

This event has passed.

Video Transcript

00;00;04;02 [Robert Bonnie]: Welcome everybody. My name is Robert Bonnie. I lead the Bipartisan Policy Center's Farm and Forest Carbon Solutions Initiative. I'm glad you could join us today. I think we have a great program. Let me first tell you a little bit about this initiative. I'm going to talk a little bit about a subject we're gonna discuss today, and then I'm going to introduce our panelists. We're going to have some time at the end of the discussion today for questions. You can use the chat function in YouTube or Twitter to ask questions and we'll ask the other panelists. So

00;00;33;22 first a little bit about BPC’s farm and forest carbon solution initiative. So the goal of the, of this work is to work with a range of stakeholders in agriculture, forestry, conservation, environmental groups, and others to develop a policy agenda that can help us tackle the climate challenge we face, but do it in a way that builds bipartisan support. Um, and we're going to be hosting a series as part of this ever going to be hosting a series of webinars to discuss important issues. We hope to

00;01;06;05 clarify issues, provide some good discussion, and help point towards a bipartisan roadmap that can help policy makers in Washington find an agenda that works for the climate, but that works for rural stakeholders as well. When most people think about climate change, they think about energy for, for very good reasons, right? Most of the focus has been on greenhouse gas emissions from from fossil fuels, but land

00;01;33;19 has a critical role to play in climate change. And, uh, in the United States, forests are an enormous, uh, carbon sink, about 15% of the co two that goes up in the air every year, comes back down, uh, in our forest, just through the regrowth and of, of forest in the U S agriculture contributes about 10% of greenhouse gas emissions in the U S but there's an enormous opportunity to reduce those emissions.

00;02;00;06 [Robert Bonnie]: Even while we improve the productivity of agriculture. And importantly, we can sequester carbon through, uh, uh, improved soil management, grassland conservation, a variety of practices. Um, and so if we're going to meet ambitious climate goals, we're going to need, obviously to think about reducing, uh, greenhouse gas emissions, but importantly, we're going to need to think about negative emissions. We're going to need to think about how we pull CO2 out of the air. Uh, and, and,

00;02;32;00 uh, in the case of agriculture and forestry, put it into soils and, and, uh, ecosystems. And one of the most interesting aspects about agriculture and forestry when it comes to climate change is that there's a lot of alignment. And by that, I mean, many of the practices that farmers ranchers forest owners can undertake to address climate change can be very compatible with, uh, production, agriculture, production forestry, um, uh,

00;03;02;00 and so that alignment gives us an opportunity to structure incentives and markets in a way that, that benefit rural stakeholders, rural economies, agriculture, and forestry, and help us, uh, solve the climate challenge for this webinar. We're really gonna focus on soil carbon and particularly, uh, in crop land. Um, and we've pulled together a great panel today. We're going to talk about the issue from the point of view of both the science around the

00;03;30;09 issue. Uh, we're going to talk about how this actually works in practice on the ground in agriculture. We've got a, um, a farmer who's been doing this for a long time. Who's going to help us with that. And we're also going to talk about it from a business standpoint and look at the business opportunities in soil, carbon sequestration in, in, uh, in croplands so great to have you all here. Again, if you want to, uh, ask a question, do it through the chat function and in YouTube or Twitter, uh, I'm going to

00;03;59;07 introduce our panelists and then I'm gonna, uh, uh, turn to questions. So first we've got Wayne Honeycutt, he's the president CEO of the Soil Health Institute.

00;04;09;11 [Robert Bonnie]: Um, uh, I'm going to have Wayne talk a little bit about what the soil health Institute does. Wayne importantly was the deputy chief at the natural resources conservation service at USDA. Um, during part of the time I was at, uh, USDA, he oversaw all the science work there prior to that had a distinguished career as a research scientist, uh, at USDA. And he was critical in starting that soil health initiative, uh, that NRCS is, uh, has had going for, uh, for some time he's, he's been the recipient of the Hugh Hammond Bennett award from those, uh, soil and water

00;04;42;00 conservation society. Most importantly, uh, he's uh, like me, he's a Kentuckian. So thanks for joining us today. Wayne, we've got Fred Yoder, an Ohio farmer, a business owner. He is, uh, been farming for nearly 40 years in Ohio. Um, he also has been involved in seed business there, but Fred is known, uh, not only in the, in the

00;05;07;18 United States as a pioneer in, in soil health and carbon sequestration and agricultural lands. He's known internationally as well. Uh, I've worked with Fred, uh, in as part of international negotiations, uh, around the, uh, global Alliance for climate smart agriculture and other things. So Fred is, is known, uh, uh, across the U S and internationally, as I say, and then we've got Laura Wood Peterson who's with, uh, Indigo agriculture. Um, uh, she's a senior

00;05;38;01 government relations there she comes. Uh, prior to that was with Syngenta. I got to know Laura when she was at the national association of conservation districts and also working with the Russell. Group's been a distinguished career in, uh, in agricultural policy. She's got a law degree. She's, she's taught, uh, policy and politics, um, uh, lives with her husband Jeff in Montana and operates a cattle ranch there. So

00;06;07;17 thanks for joining us today. Let me, let me, uh, jump right to the questions. Um, Wayne, I want you to talk a little bit about the soil health Institute, but then can you tell us a little bit about the science behind soil carbon sequestration? What, what type of practices are we're talking about here that, that can, uh, store carbon in the soil?

00;06;28;10 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Yeah, sure. Well, thanks very much offered in, first of all, thanks to the Bipartisan Policy Center for the opportunity to visit with you all today. Uh, yeah, a little bit about the soil Institute. Uh, we are a 501 C three nonprofit, and our mission is to safeguard and enhance the vitality and productivity of soils through research and adoption. Uh, that adoption can take place in many different ways. Uh, we look at, for example, things that will influence the adoption and things like that. Farmers need to know when they're deciding whether or not to adopt these

00;06;58;02 soul health systems, things like information on the business case, the best measurements of some training programs of the impacts that will have on things like water quality and carbon, because then that influences policy, uh, also the best research that needs to be done, and also how we can take some of that information to influence consumers, essentially to create more of a market demand for food and fiber and fuel that's grown using these soil health systems. So that's just a little one-on-one, uh, on the soil health Institute. Uh,

00;07;27;25 I'd love to visit with anybody, uh, anytime in the future, more in depth if you'd like to about the Institute. Um, yeah, your, your question about kind of about carbon sequestration, kind of the science behind it. Um, I think the fundamental aspect of that science is that it's been going on for, for many moons of, for, for millennia. And that's kind of really kind of starts out with the carbon cycle. And, uh, so I'll give you a kind of a quick one Oh one on the carbon cycle. Uh, essentially you can think of it kind of is

00;07;57;16 inputs and outputs and the balance between the two. Uh, and if that balance, uh, ends up being that there are greater inputs, uh, then you can end up with greater carbon sequestration. If that balance ends up being more atmospheric outputs, then you have those losses of CO2 to the atmosphere.

00;08;16;03 [Wayne Honeycutt]: And so to get a little bit more specific, uh, think of photosynthesis. So that's when plants bring in CO2 from the atmosphere and they essentially store it in their plant vegetative matter, and they form carbohydrates, uh, other carbon compounds, when those plants die, then they returned the leaves and the stems and roots and things like that to the soil. And so now you kind have a management, uh, option a, is your option going to be to till that soil, and then therefore when the microbes

00;08;47;12 decompose it, plant material and give off CO2, now you're going to be releasing CO2 to the atmosphere, or do you decide to no, till that soil leave that plant material on the surface, not disrupt the soil and not disrupt the native organic matter, that's there that organic carbon that's there. And so it would be much more slowly decomposed, and you can gradually build up that carbon in the soil that way. And this kind of a, kind of another kind of practices, things like cover

00;09;15;23 crops. Uh, you know, you have a particular time of year between your main crop and when you plant the next crop and when a lot of times something is not growing and, and generally only about 5% of our profit line, you're using cover crops right now. So that's a huge opportunity and huge potential because again, thinking of inputs and outputs, there is another opportunity for having additional carbon inputs into the soil is if you can grow a cover crop. And so that's an additional opportunity for more carbon

00;09;46;15 into the soil. So that's kind of a, kind of the basics of what it boils down to. Sure. They're very, very detailed complex studies, you know, that have, um, that look at me, these different relationships, but that's really what it kind of amounts to is a balance of between your carbon inputs and your outputs and your management decisions that influence that balance.

00;10;07;27 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Now, I would say before I turn it back over to you, Robert, um, kind of, uh, your question about kind of that scientific basis for it. When I first came to the soil Institute four years ago, one of the first things I did was put together a white paper where I looked at what research literature was out there on the impact of different management practices on carbon. And one of them that I looked at laws no till and quickly found 27 different literature papers, papers in the peer reviewed

00;10;38;08 literature. And, uh, out of those 27, 25 documented an increase in the carbon, in their soil from adopting no-till. So 25 out of 27, that's a pretty good bet in my book. And, uh, so it's, it is well-documented that a lot of these soil health promoting systems and practices can significantly increase carbon in your soil and really help, uh, fight mitigate and fight climate change.

00;11;07;22 [Robert Bonnie]: I want to, I want to turn to Fred now and Fred, you've been a pioneer in this community. As I mentioned for a long, long time, you've been a producer, stepped out early to implement many of these practices. I'm interested in your own decision, your family's decision to implement these practices, um, why you chose to do it and how, how it works, what the risks are that you and other producers on. And Just a little sense of kind of how this works on the ground.

00;11;36;01 [Fred Yoder]: Sure. Well, Robert, first of all, thank you for, including me in this webinar and people that know me, I, I get very passionate about the soils and, and farming in a different way. So, uh, actually it was early into my farming career that, uh, that I actually saw something happening on the farm that, that didn't make sense. Uh, we had a pasture that had never been farmed. It was right beside a, a field that we had been farming for years. And so we ended up taking the, the fence row out and we, we mold were clouded and it was just remarkable. The,

00;12;08;03 the, the, the soil Tilth, and this was lighter soil and how rich the soil was. And, uh, and I thought, well, that's really nice. I couldn't understand why my, uh, field right beside it was so bad, but it only took less than five years. And that brand new ground has been fine for only five years, ended up being hardened and, and a flat like the stuff we've been mobile or plan for years. So early in my career, I realized we're doing something very

00;12;36;06 detrimental to the soil and we can't figure this out. So, so my thinking was, if, if that soil was so good and it's never been touched, except we run cattle on it, it's all we ever did. What am I doing wrong? And so that's when no till started appealing to me. So later on, we started just know, telling us soybeans into corn stubble and, uh, later on, uh, I thought, well, the worst good for soybeans. Why didn't it work great for corn? And, and back then, we didn't necessarily have all of the technology

00;13;05;24 to take care of some of those issues with, with corn planting, but you just, you just have to manage it.

00;13;12;01 [Fred Yoder]: So as much as anything, I did it for economic reasons. So, I mean, I was thinking out, you know, if there's not much money in farming, then it's just important to take a dollar off of input costs as it is for putting them putting a dollar on for, uh, you know, increased markets or volume in productivity. So I will tell you this, uh, the less, I mean, then the big phobia and the big fear that most farmers have is, well, shoot. If I go to no till, um, then I'm going to give up eel

00;13;42;01 and, you know, you do go through a, kind of a, of a, a time where you have to kind of recondition your soils for, um, for, uh, you know, for no, till, you know, one of the things that, and I hate to say this, but I kinda blame some of the land grant universities. We were always taught if you had X, Y, and Z to your soil, mix it in and you'll get a good crop and it's true, but we weren't paying any attention to what was happening below the soil surface, the whole microbial activity, the soul, or the soil is to really live and breathe and grow. And so I

00;14;12;06 really appreciate it. But Wayne was saying, we really got to understand, you know, the benefits of soil health is going to help us in higher yields, but also a manager at risk for, for some of those times when we run out of water. So, so basically if you give me, give me a farmer and get them to go three to five years and no till I'll have them for life, because by that time, you've given a chance for the ground to re reconditioning itself and the microbial actions picks back up and, and you start building that

00;14;40;30 organic matter because you're sequestering carbon and not releasing it, you know, as a, as a young man, when I was clowning for my father, I used to love farming plowing with the, without a cab on the tractor tonight, I could just smell that dirt.

00;14;53;30 [Fred Yoder]: It was just touch it. It was almost like a, it was just an enticing enrollment. And I realized later on that I'm releasing carpet. That's why it smells good. And that's why we get a yield increase, but it's, it's just like stirring the embers of a fire eventually that it burns out and then you lose. And so that's what we have to do to put those ambers back in, keep them in places and make sure that we go ahead and, and grow that soil health rather than, and spend it. So, uh, give me three to five years and I'll get farmers to, uh, to stick with, uh, conservation

00;15;23;21 tillage.

00;15;25;18 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. So we've gotten some of the science, we've gotten some of the practice. Laura Indigo is, is looking at ways to monetize this, to provide, to find value in carbon sequestration. Can you talk a little bit about Indigo's model and how soil health fits into it?

00;15;45;12 [Laura Wood Peterson]: Yeah. Thanks, Robert. And I would echo, it's so great to be here today with Wayne and Fred and appreciate this conversation. Having grown up in agriculture, I think advancing soil health is a way of doing business. That's increasingly important. Indigo is leading a means for ag to contribute more meaningfully or differently as a climate solution. So we're an ag tech company. We focus at the nexus of environmental sustainability technology and consumer health. And in taking a systems approach to the supply chain, we offer four complimentary

00;16;17;18 offerings that really began with where Fred you're just left off with the microbiome. And so our Indigo microbials are nature-based seed treatments that think about reducing synthetic inputs and reinforcing plant health through what are you sufficiency or nutrient intake stress tolerance. Our second offering is Indigo marketplace, which connects farmers with a broader network of buyers, thinking about identity preserve, or specialty

00;16;44;10 grown products.

00;16;45;24 [Laura Wood Peterson]: This business model, or, or almost platform makes large scale transactions more accessible. And, you know, we support farmers with a suite of products that accelerate on the benefits of transacting this way. Our third business unit Indigo transport enables us efficiency. And finally, Indigo carbon is a carbon market that connects farmers with those that may want to offset their carbon emissions from a business side and through drawdown and ex soils, which is, I think we'll some we'll keep coming back to in this conversation. I think driving this business model

00;17;17;15 are the inescapable realities that we know we all face globally feeding and fueling our world in a more beneficial way. Necessitates changes across the supply chain. We know from all of our colleagues, such as American farmland trust and some of the great work on land degradation members, um, recently read Texas farm Bureau. You know, we lose 2 million acres of farmland to development in the U S every year and globally, we're degrading about 25 million acres for your approximately 30% of global land is fully

00;17;47;01 degraded. So how soil health that's in a business model is a really curious question that goes back to our mission and how we think. So it helped advances a more beneficial system. So through our platforms, through our core offering, um, this can span sustainable land use. This can span how grain is produced in a micro bridge environment that may have beneficial attributes important for human health. And, you know, Robert, um, earlier

00;18;14;03 this month, CNN covered your colleague from the Bipartisan Policy Center, a former Senator bill Frist, who made the point, the American food system is not broken, it's functioning as designed. So it's, so when we optimize for efficiency, rather than resilience, you know, we've had some benefits in efficiency, but farmers aren't necessarily economically better off than they were in 1975. And our net farm income is really difficult right now. It's very low and our consumers have to be looked at in terms of consumer

00;18;45;06 health and those outcomes there. So we think of distinguishing between optimizing production and maximizing production. You said any goal, the American farmer will figure out how to meet it. So we questioned the goals and at Indigo, from questions we grow to the value of today's discussion is thinking about the policy goals that might benefit soil health that also drive business outcomes.

00;19;09;21 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. Um, Fred, let me, let me turn it back to you. You talked a little bit about the impact on yield, and I'm assuming for folks in agriculture, that's obviously a critical, um, uh, you know, a critical issue. How does this affect the bottom line? And so I'd love you to elaborate a little bit more on that, and then maybe how it's influenced, uh, uh, your, your other inputs, uh, fertilizer use and other and other things.

00;19;36;27 [Fred Yoder]: Sure. Well, actually, you know, there's, there's more or less two different kinds of farmers out there. You got some farmers that, that it's yield, yield, yield, and no matter what costs, and what's the, what's the highest meal we can possibly get, but then there's other farmers like me that I like to see how much I can produce with less. So, you know, how do you produce more with less? And, and one of the things that I've tried to do is limit all along my inputs, but you also have to understand, you know, what, what's the limiting factor in yields. And a lot of it is just stress. And so how do we

00;20;08;26 manage that, that, that, uh, the difference between, you know, the highest part of the yield in the field and the lowest part of the yield, and we were having swings of almost 50% of it's like I take corn, for instance, the highest yield might be 200 bushels on the lowest might be a hundred. So how do you have such a wide swing? And a lot of it was just based on, on organic matter, not so much, uh, fertility, because we took soil samples and it was just as fertile and then a lighter soils. It was the darker

00;20;38;28 soil, but the biggest thing that was missing was the ability to hold water.

00;20;43;06 [Fred Yoder]: Well, we all know now, if you can increase your, your organic matter by 1%, that's an extra 25,000 gallon of, of a capacity you can hold in your soil. That means that, you know, when you get a big grainy event, like we've been getting for the last several years, uh, you can, you can hold another 25,000 gallon of water. But that also means that when it turns really dry, like it is right now in Iowa, we have an extra 25,000 gallon of reserve. So, so you really, you know, it's a lot of emphasis about managing the risk and, and, you know, farming is a business

00;21;13;20 right now, you know, things are tough to, uh, to make it on your farm as, as Laura said. And so how do we, how do we make healed and how do we manage that risk that we're having? And so we start really paying attention to the soil profile and the soil health. And I'll tell you, I can't believe how much farmers are now interested in soil health compared to just a few years ago. So that to me is really, really important. We have to pay attention to what's happening below the soil surface. The other thing too is, is here in Ohio. We have a lot of

00;21;44;01 issues with, with water quality up in Northeast, Northwest Ohio, with the algae blooms and in, uh, in Lake eerie because we have dissolved reactive phosphorous that are that's leaving. So one of the things that we've been doing a lot here in Ohio and other places too, is, is how do we, how do we, um, how do we keep that, uh, those nutrients in place, but instead of having to replace them all, I mean, if you have a big rain event, like we

00;22;10;13 had in the last several years, uh, you know, like two years ago, we had five rain events during the growing season of two inches or more that's never happened.

00;22;17;24 [Fred Yoder]: So, you know, you can say, it's not climate change. It's just weather pattern changes. But if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it's probably a duck. So you gotta figure out a way to, to manage that. So that's why I'm a big proponent of, of, of, of cover perhaps too. That's once you re harvest the crop, then, you know, there's, there's excess nutrients to there that you need to, to scavenge for the next crop. So that's why we use a cover crop when of the windows that cover crops, a decay, and those roots, uh, have extra plant food right in there it's

00;22;47;21 available for the next crop. So the, one of the things that the farmer starts to realize is it is about economics. And I'll talk later on about that's how we really get the climate smart agriculture system to work for brawl farmers, but it starts with economics, but I'll guarantee you, once you go down that economic road, you will see benefits that you never seen before in making this food factory a much more resilient for times when, when they get blood rough. And, and that's, that's the other thing too, is, is when you would adapt

00;23;17;06 to, to some of these changes that we have to do, uh, you, you, you do it and not even realizing what, what you're really doing at four, but it's all about managing risk, but it's also a way to continue to have high yields. We have a saying in climate smart agriculture about sustainable intensification, and that might seem like an oxymoron to some folks, but that's what we have to do. We have to figure out ways to, to produce more, uh, on, on a, on a regular basis, have less variability in the field, but

00;23;46;23 you do that by increasing your microbial action in your foot, in your soil. So, uh, if we, if we continue to do this, the yields are going to be there because you're, you're, you're usually about a mineralization more than in a lot of organic material in your soils, rather than then the synthetic, uh, nutrient that you're putting on, uh, as an additional nutrient.

00;24;08;04 [Robert Bonnie]: That's great. So I want to turn it back to you, Wayne. And we talked a little bit about, uh, nutrients and, and, um, one of the, um, issues when we think about climate change in agriculture are nitrous oxide, emissions, nitrous, oxide, very powerful, uh, greenhouse gas. And so managing nitrogen in particular is going to be important. Fred talked about some of the water impacts that we've, we've seen a lot of places with phosphorus nitrogen, uh, important in water quality as well. Can you talk a little bit about soil health and nutrients? There's some

00;24;42;06 concern that maybe some of these practices might invite more fertilizer. Um, can you give us a little clarity on, on how this might impact, uh, nitrogen use and nitrous oxide emissions in particular?

00;24;55;09 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Yeah, absolutely. You know, I, I know there was a recent article that indicated that, uh, if you, uh, have been increased carbon sequestration, it would require greater nitrogen fertilization. And, uh, I'm sorry, but that's just not the case. Um, it is true that microbes in the soil, they do, uh, all their best to maintain a balance between the amount of carbon that's in their bodies in relationship to the amount of nitrogen that's there. Uh, but when they have like a carbon rich, uh,

00;25;28;08 substrate like straw or something like that, that they're feeding on, um, that does not mean that you should fertilize with nitrogen for them, you do not fertilize the microbes, uh, and stick cause what they will do is they will then scavenge the soil for loose, uh, nitrogen, uh, and, uh, they essentially would subprocess process. They call immobilization it's, it's a well known, documented process.

00;25;52;07 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Uh, and so you not need to fertilize for the microbes. Uh, so having increased carbon sequestration does not require, uh, additional nitrogen fertilization. Um, it is also true though that this carbon, when it's tied to things like nitrogen, when you get a more, uh, healthy soil and more biologically active soil, the microbes will feed on that carbon. Is there any energy source and release things like nitrogen and phosphorus, that's tied to that carbon. And so that's one of the sources of the reductions and inputs that, that Fred was describing is now

00;26;26;04 you may be able to basically rely on some of that enhanced nutrient cycling, uh, within your soil and be able to reduce your inputs. Uh, and so that's one of the great, great opportunities. Another thing that you can do is when you increase carbon in your soil, you're essentially, or you can kind of think of it. It's a, it's a nontechnical term, but, uh, fluffing up the soil, you essentially make it less dense, but the more carbon in it. And what that

00;26;52;10 means is that a roots can penetrate the soil better. Ancon can scavenge those nutrients. And so, uh, also as Fred mentioned, increase water HONY capacity. So you get more water than now, the nutrients can travel in that water to the roots. And, and so you can really improve, uh, your whole nutrient use efficiency or recovery of any additional nutrients that you've added. You can really enhance that recovery or that use sufficiency by the

00;27;19;22 crops when you improve soil health and carbon is not the only content, you know, so health is definitely a very, very key, uh, determinant and influence around soul health.

00;27;31;27 [Robert Bonnie]: Can you talk just briefly about how we measure soil carbon, if, if from a policy perspective where we're thinking about making investments in these types of things, is this measurable? What kind of data do we have? And then I want to turn to Laura to talk a little bit about how Indigo uses data in their work.

00;27;50;29 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Now, you know, we've actually been measuring Carmen for decades. Uh, they're really well-established methods for it. Uh, the is there's a method call it combustion method where, you know, essentially bring the sample to the lab and in that combustion at a very high temperature and analyze the carbon that's in there. Um, there are some more, uh, recent, uh, methods that are there for field based. And, um, those use the techniques, they call them spectroscopic techniques where you essentially look at a particular wavelength of light and estimate the

00;28;23;11 carbon that's in it, in the soil using that. And so that's very promising. Uh, but the piece, I guess, that people often don't kind of recognize is that you also really need to measure the density of the soil. It's not just the concentration of carbon that's there, but it's the total content that's there. That's really important. And just very quickly, I'll try to make just kind of an analogy of just kind of like a swimming pool analogy. You can put a drop of red dye and a

00;28;52;21 glass of water, and you can see a lot of it there still, but if you put a drop of red dye in a swimming pool, it immediately dissipates because you've really reduced the concentration of it. You've put that same content, that same amount of red dye in, but it's just less concentrated in the glass, in the pool versus the glass of water. And it's kind of the same thing with soils is that when you're just measuring the concentration of

00;29;20;03 carbon in the soil, it's useful information, but you also have to measure the density of the soil in order, really, to be able to know the total content of carbon that's there. And so right now that is also an additional type of field measurement that needs to accompany that carbon measurement in order to have the most effective information for making management decisions, uh, for, for selling on carbon, carbon markets and things like

00;29;48;06 that. Uh, there there's one or two new techniques that allow you to also measure that in the field, uh, that gives you the, in the field. Uh, but I won't go into those right now, but I think you get the idea that there are measurements available. Uh, some are more complex than others. Uh, if there are some new ones on the horizon that are very promising to help us do it in the field in an accurate way.

00;30;11;15 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. Laura, talk a little bit about how You all think about measuring it, The technology data management that Indigo is using. Yeah.

00;30;21;11 [Laura Wood Peterson]: I think that to build on Wayne's points here, um, we view technology and data as critical as an ag tech company. Of course we do, but it's really going to be critical and measurement and verification of the on farm greenhouse gas emissions, um, using a variety of metrics and data gathering some of what we talked about, you know, as well as the grazing patterns are chemical applications, nitrogen applications, even just yield combined with our geospatial intelligence platform, Indigo

00;30;51;22 Atlas, which can confirm tillage events or cover crop usage. It's this new age of remote sensing, um, machine learning, um, and, and really algorithms coming in for deeper understandings and in field conditions that lower costs. So it's a balance of kind of getting the costs down by using technology and this leads to better outcomes and of themselves when farmers have real time insights in hand, but also it goes at how we are able to

00;31;20;24 think about a carbon market. So the data we collect along with the soil samples, um, runs in a bio G chemical model, and this is how we assess the carbon levels and calibrate the models with new soil samples. So we welcome all, uh, innovators and entrepreneurs to think about effective ways to measure through our territory challenge. So if you'd like to learn more, please let us know.

00;31;46;08 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. So I want to, uh, I want to turn back to Fred now and, um, if we're going to be successful, uh, at making a significant dent in the climate challenge, we face, we're going to have to have broad scale adoption of these types of, of, um, uh, soil health practices. Um, and as a, as a producer, what what's going to be most effective in, in, uh, communicating with farmers, working with farmers, persuading, producers, to

00;32;19;14 adopt these types of practices. How, how do we, um, you know, how do we, um, make this work with producers and increased levels of adoption?

00;32;29;29 [Fred Yoder]: Great, great question, Robert, uh, one of the things that you mentioned earlier, I've been involved with the, uh, climate smart agriculture clear around the globe and through the global lines of climate smart agriculture, which I got to work with you, Robert, uh, I became the chair of the North American climate smart agriculture Alliance. And basically what I like about it is they're talking about three pillars. The three pillars of climate smart agriculture is number one is productivity, farmers love productivity. That's how you start and get the farmer

00;32;59;10 interested in and trying something new, but it's going, it's going to have to be an economic incentive. The second pillar is adaptation and resilience, uh, which we have done that in many different ways with precision agriculture and more timely ways to do it, but more by diversity. Uh, again, building that organic matter up. So we have more capacity to water.

00;33;19;19 [Fred Yoder]: And then the pillar three is soil secrets, duration of carbon or reduction of your greenhouse gas emissions, but you're not going to get farmers interested in starting with pillar three. You've got to start with pillar one. When you get pillar one and you get more productivity by certain majors of, of, you know, increasing your soil health, and then you learn to adapt and you have all those tools in the toolbox. So if you do have adverse, uh, and challenges, uh, coming, uh, to yet you have those tools that you can do. And then all of a sudden guess what pillar three happens automatically. And so that's why I really think

00;33;51;28 it still comes back down to an economic incentive for farmers to get them into under the tent and get them interested in that and pro you know, sequestering carbon, and then maybe getting paid for it, like, like Laura's company is doing and others are going. I really do believe it's going to be the key. Uh, you know, my son often says, you know, farmer's notorious for over-producing where we have a blood of corn. We have a blood to soybeans glitter. Wait, can you imagine what we

00;34;18;01 do if we were all in charge of growing carbon and putting it in, getting paid for carbon way, we would, we would definitely over produce. We would have carbon sequestered, like we've never seen before. And especially if you decouple it from the price of, of the commodity, in other words, make, make, um, uh, carbon and other commodity. I think you'll, you'll see a lot of farmers, uh, switch instead of, uh, the Tilly sip system that they're on now. So that's, that's how you really get it, because the other thing I mentioned earlier about the resilience in your, in your fields, you got to

00;34;48;04 get rid of that, the, the wide variance in your field, like, you know, that, uh, 50%, uh, uh, gap between your, the highest producing acre and the lowest producing acres not is not, uh, acceptable.

00;35;00;20 [Fred Yoder]: You have to get that down to Reno, maybe 20%, something like that. But the other thing you can do as you don't go through this, as you produce more, um, uh, organic matter, you can, you can reduce your nitrogen application. That's the thing that I'm a big proponent of no till and cover crops. And we have been able to, uh, even reduce our chemical, chemical, uh, application, because when you have a growing cover crop over the winter, you crowd out all those winter annuals. And so we actually save a, a, a spraying in the spring. We, we plant right directly

00;35;32;20 into the cover crop and then kill it later. Uh, the other thing we're doing now, we're trying to do is maybe, uh, produce a companion crop. What if we put up, you know, uh, uh, some type of Clover in there, so we can actually have a companion crop, and then maybe, maybe we have to delay our, our corn planting, uh, like, uh, most people don't like to do in the, you know, in the, in the conventional world, but it might be more successful if you

00;35;59;03 plant your soybeans maybe at first and, and plant your corn later, let that, that, that, that companion crop go, and you can reduce your nitrogen application by, you know, 20 to 50%. So I'm all about finding a ways to do more with less than, and I really think that as farmers finding success after success on their farm, they're going to continue to do more. But again, it comes back to that economics, you show it, you show a farmer that by putting the no till and cover crops, that the can save a loss of nitrogen or loss of phosphorus or loss of, you

00;36;27;28 know, any kind of nutrient, you know, and in fact, if you look at how much nutrients we've been losing in, in Ohio here anyway, except that it can be a hundred dollars an acre, all of a sudden the farmer takes notice of that. Okay, I can meet, I can save a hundred dollars of input cost if I just do some of these practices. So again, once you get a farmer in, in the, in the, in the Tandon and sees the, the, uh, the tremendous improvement in the soil and his, his risk of reduction, you'll have them forever. And that's

00;36;58;01 really how you get farmers interested. It's economics.

00;37;02;16 [Robert Bonnie]: Laura, what about Indigo? What Do you all engage? Um, landowners in thinking about getting to scale. What's your all's model. Yeah. I should have said Producers and growers rather than landowners, but you get the idea,

00;37;18;02 [Laura Wood Peterson]: We'll take them all. So Fred said it takes an economic incentive, and that's what Indigo is providing In a set dollar amount per ton of carbon, as well as the infield agronomists to help with implementing practices. We talked about the measuring, um, and then the actual registering with the formal acknowledgement of a carbon Trenton credit. So in partnering with the scientific community with leading third party, such as climate action reserve and Vera, uh, this is how we create the transparent, dependable

00;37;47;18 credits and rally others around this opportunity. And the grower reaction has been, um, extremely encouraging. We've seen over 21 million acres of farmland express interest in Indio carbon and over 7 million acres enrolled. And it's not just Indigo finding these positive results. Um, we're all here talking about, you know, Agra pulse reported last week on the cover crop survey from CTAC, uh, you know, the percentages of farmers showing increased yields are better weed management, um, and savings on

00;38;17;17 inputs are very real and very in line with the reported findings from the USDA census from 2012 to 2017, which found a 50% increase in cover crop Anchorage. So it feels like farmers, um, see a way of connecting with the changing trends, the changing tides of a consumer interest, and feel that support more broadly. And I think it would add, uh, Robert not just with the growers, but the interest we've seen from the demand side is also really

00;38;46;24 interesting and exciting when we think about, um, encouraging other businesses from a business perspective on the value proposition. That's very distinct in agriculture. You know, in fact, last week, I'm losing track of weeks now with COVID. I think it was this week, the Senate released its climate report on, um, you know, some policy overarching goals inside of the national academies of sciences that said, um, maximizing carbon storage capacity and lands is generally the most cost effective

00;39;18;26 carbon removal technique available today. So making sure the demand side has that, um, view into agriculture is, is really, really worthwhile given, um, what we, what we hear from the national academies of sciences.

00;39;35;00 [Robert Bonnie]: Wayne, I know the soil health Institute has been doing some interesting work with crop consultants and other folks. Can you talk about some of the outreach and how the you all are doing and how that those types of approaches might allow us to get to scale as well?

00;39;48;02 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. You know, I think we could own a number of things here, right? Uh, as Fred was mentioning things that looking at the business case, some of our work also not only the business case, but also, uh, I'll know the best measurements for farmers to use and, and our soil health training program, a big part of our outreach program. Uh, we, we take the approach that we realized that we're not going to be there every day, all day long. Uh, but instead of parachuting in and given a train and then leaving, we set up farmer to farmer networks, uh, and

00;40;20;19 where we identify particular farmers who are already successful at using the soil health systems. And then basically we pay them a hand stipend to be a mentor to others, and to have field days at their farms and things like that. And so then we incorporate workshops with them, and then we also work with some of the local technical specialists, people that already know the climate and what crops grow will there, what cover crops will work

00;40;46;19 there when they need to be planted by when they need to be terminated by those types of agronomic decisions that, you know, their knowledge of the local area and the trust that they already have with farmers, you know, helps kind of bridge some of that gap.

00;41;00;26 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Um, and so that's kind of the, the gist of our, um, our outreach program with our, with our training program, that farmer to farmer networks. Uh, but then we also, um, are working now, uh, with, uh, the certified crop advisors. And these are, you know, consultants. Uh, they actually, there's about 13,000 across the U S in Canada, uh, certified crop advisors. And, uh, our estimates and understanding is that each one, uh, touches on average about 20,000 acres of, you know, their consultation,

00;41;34;16 they provide to farmers. And so when you do the math, that's about 65% of the crop land acres in the U S uh, that those certified crop consultants, uh, uh, or crop advisors I should say, and that they touch. And so we have a training program, uh, that we're all doing by webinar right now just started about a month ago, um, where we have about six webinars on how the

00;42;00;17 best measure for soil health, you know, and how to best measure for carbon. How, when you, how you influence on health, change it, uh, through different management practices, uh, what those changes mean for the water cycle, uh, the nutrient cycle, the carbon cycle, uh, what it means for economics. Uh, we have an Aggie economist that we'll be talking and when the month rolls around for him to do a presentation on it. And so those are some of our outreach of programs that we have. There are certainly some other very fine ones out there. Those are the ones that, uh, that we have

00;42;32;07 at the soil health Institute.

00;42;35;07 [Robert Bonnie]: So I wanna, I want to turn to a policy now and get your all's recommendations around policy. I want to remind folks that they can ask questions through the chat function on a YouTube or Twitter. We're already getting a bunch of really good questions where we're going to get to right after the, uh, the policy question here, Laura, as you, as, as Indigo looks at federal policy, are there things that Congress can do, uh, to, to advance, uh, soil carbon sequestration that would be beneficial to

00;43;05;05 the work you all are doing?

00;43;08;18 [Laura Wood Peterson]: Yeah. Wayne just spoke to the diversity of perspectives covered today, and we view bi-partisan leadership the same way. So building on the testimony heard at the 20, uh, the June, 2020, um, Senate ag hearing on the growing climate solutions act. We urge Congress to expand on the bipartisan leadership of senators, Braun and Stabenow and Congress members Spamburger and Bacon. Um, this bill establishes a third-party certifier program. In addition to other things that might feel like

00;43;38;17 small steps, but that are clearly very big steps because of the bipartisan nature of the work. These senators are leading. And I think what they're doing is broadening the playing field for the climate ag discussion and growing the community so that we will have the political will for whatever happens in terms of the climate bill. Um, going back to the Senate climate report, you know, it says we already have the technologies needed to avert

00;44;06;12 catastrophe.

00;44;07;05 [Laura Wood Peterson]: So, so in the ways that Congress could act, we think one idea is to advance a nature-based climate solution through a transferable federal tax incentive modeled on section 45 Q of the tax code. This is a policy tool that we think, um, whose time has come because of the technical logical advancements we've talked about today, um, made actionable by the growing climate solutions act. Senator Bennett has a discussion draft on this topic. Senator Brown expressed interest in this topic during that June hearing and in the eventual expansion of 45 Q, there

00;44;40;09 was broad bipartisan support. So it exists for corporate industrial and energy producers. Why not farmers? We think it's a particularly good deal for two reasons. The first is that it's a good deal for taxpayers and just about $35 right now, up to $50, we can get into the CRS score and what this can look like, but it's a pretty good deal given the societal value farmers could contribute. Doctor Tom Wall, this

00;45;05;15 year's world food prize Laureate, who I'm sure Fred knows very, very well from Ohio has spoken to the farmer bottom line and at approximately $16 per acre, um, he thinks this can be the ecosystem service value for farmers that, um, would cost about $64 billion globally, which again might seem high, but it's really not in the grand scheme of policy. And if we expect farmers to do a good thing for the planet, we should pay them for it. It's what Wall explains that that's the second point. This can be a good deal

00;45;35;22 for farmers, Fred Hinton, Don you know how hard it is to farm. And we all know right now how tough it is out there. I mean, in the Midwest, the farmers filing for chapter 12, bankruptcies are at levels. We haven't seen in a long time federal data showing they're up 8% from the year before.

00;45;49;28 [Laura Wood Peterson]: And the period ending in June, we have pushed government payments to 30 per six apartment income and, you know, trade and COBIT payments are expected end this year. So we're going to have to keep thinking about streams of revenue. And faculty said, if we don't, um, farm income can drop 12% next year. And I saw their numbers this morning on predicted corn prices for the next few years, and they're not too optimistic. So, so we have to think about, you know, what kind of revenue

00;46;19;25 streams do we want? What kind of market signal is needed to support carbon markets and create the stability? Is it really that different from wind and solar? Um, this kind of approach is voluntary. It's flexible, it's outcomes focused. So every acre is different. Every farm is different, and this isn't telling any farmer how to get there. Um, and of course the transferability is critical because of the reasons we just said. So we have to do something. And the interest is out there. Robert, your

00;46;48;16 research at Duke speaks volumes about the interest, um, when farmers are recipients of a climate benefit and we think it could be a tax incentive, we think it could be what, what people talked about, the carbon bank, everything we're saying from a congressional view is consistent with what administration could maybe do from, you know, a, an infrastructure, environmental goal, or a USDA goal. The Biden proposals publishes a new voluntary carbon party market that USDA proposal with Secretary Perdue and

00;47;19;02 Deputy Secretary Sinskey, um, is trying to reduce the environmental footprint of egg in half by 2050. So we believe, you know, we can stimulate the farm economy. We can accelerate the role of agriculture as a climate solution with the added benefits we've talked about, especially with clean water. Um, it's a universal metric that is scalable and can benefit from the growing climate solutions act.

00;47;42;04 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. Fred, you talked a lot about, uh, economic incentives and I'll, I'm guessing you've got some thoughts on what, what type of policy decisions or policy that could be done in, in DC that might help drive some of that?

00;47;55;17 [Fred Yoder]: Absolutely. Well, it certainly needs to have a good policy to put forth. And, you know, the one thing I'm really thrilled about is, is we actually got both sides of the aisle talking about some of these issues. Now, you know, I was around during the whole action and market deal. And then, uh, and it didn't go very well because of the whole attitude of, of additionality and permanence and things like that. But we need an enabling policy to make some of these things happen. And right now we've got some, some, uh, legislation in front of us in the Senate to, to

00;48;25;09 maybe start the process, but it needs to, we need to actually also make sure that there's universally accepted metrics as we measure some of these things, uh, like, like carbon sequestration, what we've done. And I mean, it's kind of when it's going to have to be efficient the way we do it. I mean, you can't use all of the verification of what a metric ton of carbon is, and basically be left with nothing after you verify it. So we're going to have to use science and maybe come up with some, some efficient to major so that maybe it's infrared photography, maybe it's, I

00;48;56;10 don't know what it is, but, but there's gotta be some ways to, to make sure that that people are, you know, for buying a credit, that, that it is what it is, but I'd also love to see some sort of safe Harbor prudish provision put in some, whatever the bill was for farmers, because, uh, you know, a couple of years ago we ran into the issue of, um, you know, people, Clinton cover crops, and maybe being felt like you were going to be thrown out of there, federal crop insurance. We got that fixed, but we just gotta make

00;49;23;07 sure that they complement each other. So again, give, give a farmer a chance to make things better. You'll figure out a way farmers are very notorious for being efficient, figuring out simple and better ways. So let's, let's, let's turn them loose and see what we can come up with, but there needs to be that economic incentive and the farmers will be there.

00;49;42;20 [Robert Bonnie]: Wayne, I want you to, before we turn to the audience, just talk a little bit, we think about investments in research and the science monitoring. Are there things there that you would recommend from policy makers?

00;49;57;18 [Wayne Honeycutt]: I guess I'll put it this way. It seems that folks are understanding and valuing the fact that we can increase carbon sequestration in our soils, but there seems to be low recognition for the fact that there are different carbon sequestration potentials for different soils. And I really feel like that that needs to be, that's kind of a fundamental gap that we have right now is that, um, that valuation establishing what the carbon sequestrations potential and therefore target

00;50;28;00 is for all of our primary agricultural soils and doesn't have to be done for every single one. We, we at the Institute, we know how to group them, for example, and the similar soils have similar properties and similar Genesis of how they're developed. They can be grouped together. So you can, um, assess what those targets are. And that's the way that now a farmer we're no where, how far he or she is along that continuum to achieve that, that higher level. And so I feel like that's real kind of fundamental piece of research that

00;50;58;06 needs to be done. Others, you know, we already talked about nor accurate efficient cost, effective of a ways of infield measurements for carbon. And then there's something that's kind of been hit on. A number of times is more information on the business case. One of our projects, uh, is, uh, interviewing 125 farmers across the country evaluating, you know, the economics of social health systems and on their experiences. But that 125

00;51;26;10 sounds like a lot until you distributed around the U S and realize California has 400 different kinds of crops. I mean, that type of information. Also, we just need that type of information that to really help drive adoption too. So those are some of the ones that I would highlight number.

00;51;43;05 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. So let me turn to, um, some of the questions We've got in the audience, we've got a bunch of good questions. I might, uh, beg your all's indulgence to maybe run a few minutes over our, our, our hour mark. Um, one of the questions that that folks are asking about is about, uh, transition and, uh, the transition that you talked about, Fred's sort of the, you know, three to five years to adopt these, uh, the, these types of practices. And I guess I'll throw this to you, to you, Fred, are

00;52;12;27 there things we can think about policy mechanisms, other things to help? Is this a, is this a farm conservation program, a thing that we could we to help producers with that transition?

00;52;24;16 [Fred Yoder]: Well, it could be, but, uh, it, you just got to figure out how a farmer thinks. And one of the things that you start with is what kind of equipment do you have at home? What do you got, what do you got sitting in the farm barn that you could use? Um, you know, the way, the way farmers adopt things earlier is if it's easy air or if it, if it, if it makes good, efficient sense to do it, we have a lot of, there's a lot of farmers today. They didn't have these vertical tilt machines. We put an air seeder on ours, and it it's very quick. It's a, we can, we can see, you

00;52;55;29 know, 40 to 50 acres an hour. And so that's, that's one of the ways that you can get farmers to, to try something. What did you know, taking inventory of what you have and utilize it, and again, go back and make sure that you, there is no harm that if you are signed up in some, in a different, uh, um, uh, uh, government, uh, program that you don't, you don't kick yourself out by doing a certain thing that you're not doing something, you know, they can give you harm.

00;53;21;22 [Fred Yoder]: The other thing too is it's just, you gotta just, again, talk about the potential that if, if you, and you have to build that potential, I keep I talk to farmers and talk about their, the soil or 401k, you know, everyone today, you know, including your banker. And that's another thing too, is you've got to get your banker convinced that this is the right way to go, but you gotta look at your soil as your 401k. Uh, you're not going to get a return on investment in six months or a year, but you are going to get it in five years or 10 years. You're going to see really, uh, great advantages later on the longer you do it, the more you do

00;53;55;04 it and each and every crop that you grow, you're sequestering carbon. So you continually go down into the system and change. Then you're just going to continue to make your soil better and better and better. And that's what, that's, what it's going to appeal to a farmer is you got to start the system. You can't do it one year then and get out. And that's, that's one thing that really concerns me with some of the, the, uh, uh, possibilities today. And I don't, I don't really know what, what, uh,

00;54;21;19 um, they all are, but some of them that are coming out to you, you can't be participating in cover crops and no till in order to qualify for that. And I think that's a big mistake because you're going to see farmers that are going to be tearing things up so they can qualify for a credit later on. That's

00;54;38;09 [Fred Yoder]: not well, I wouldn't touch my crop for nothing. I don't care whether I would pass on a payment or whatever, but once you start down this, you start really having, you have a different relationship with your soil than you did before. So those are some of the things you got to look out for.

00;54;55;09 [Robert Bonnie]: So what we're, we're getting, uh, a number of questions around monitoring. And one question from Catherine chin, hope I got your last name, pronounced it correctly. How, how do we get monitoring done cheaper and quicker? And am I first throw it to you, Wayne? And then Laura, see it. If you've got some insight on that for the work you're doing as well,.

00;55;17;17 [Wayne Honeycutt]: I guess I think that you kind of have to decide first kind of what you're willing to accept in terms of, uh, levels of uncertainty. Uh, you know, it's that, um, boots on the ground samples, um, out of this soil and measure it in the lab that will give you the most certainty, but also at the higher cost. And, uh, but then there are others that you can, uh, monitor remotely, you know, a satellite images on whether or not particular practices are in place. And then you can use models, uh, to help you predict what those

00;55;50;24 changes in carbon are based on those practices that you see in place, you know, things like, is there tillage or no tillage? Is there, are they using cover crops or not? Are they harvesting the corn just for grain? Uh, so you have a lot of residue returned to the soil. A lot of carbon therefore returned to the soil or are, is the, uh, corn being harvested per silo. I mean, they're cutting, you're removing most of it, you know, and so all those types of management things can be, uh, uh, decisions can be monitored

00;56;19;17 remotely, and therefore you can, um, do it relatively inexpensively. If you are willing to accept that you're not having a measured output, that you're having a model impact. And so that's kind of the, the key, uh, crux, I think to kind of answer that question is what are the levels of uncertainty and therefore, um, the techniques, uh, appropriate for that level of

00;56;45;24 uncertainty that you're willing to accept.

00;56;49;07 [Robert Bonnie]: Laura, anything you want to add on kind of monitoring costs and how we make this easier and cheaper for producers?

00;56;57;15 [Laura Wood Peterson]: I think Wayne hit it. The only thing I think I would add is that the more that platforms are able to talk to each other, the Mo more open source, the more RMA and FSA and NRCS data is able to be used. Um, and again, protecting producer, privacy is always central to however data is used, but, uh, I think that the more data going in there more machine learning has, um, a role here.

00;57;24;29 [Robert Bonnie]: Great. One question Wayne, and I'll throw this to you, and then others should chime in if they've got thoughts on it. But there's a question About bio char and, um, about the potential role of, of bio char and these, These systems. Can you just quickly say what bio char is, and then it, uh, sort of the, your organization's views towards bio char and the opportunity?

00;57;49;19 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Yeah. So bio char is, you know, it's, it's essentially, um, I guess I look at it as kind of a, another amendment it's very carbon rich, um, like, um, it's different than composts that kind of would put them in the same way is that it's something that, um, you know, you would be another input that you would bring into your farm, uh, and, uh, that then you would apply. It's a very effective, uh, immediately, you know, increasing your, your carbon because that's what you're doing.

00;58;19;05 You're, you're adding carbon. Uh, and so with similar kind of compost, there's a lot of benefits, um, increasing water, holding capacity and nutrient availability. Let's, let's call it head and exchange capacity, things like that. Um, so you can really most immediately improve the healthier soils, chemically, physically, and biologically. Um, but there are other ways that you can also do it, um, which are, you know, kind of what every farmer has under his or her control that doesn't necessarily

00;58;51;20 require, uh, additional purchase inputs, uh, except for maybe C uh, you know, cover crop seed and things like that.

00;59;00;04 [Wayne Honeycutt]: And so, um, you know, there, you can, you can still get there. You can still climb that Hill. It depends on what path that you take to get there. Uh, but you can also use a rotation crops where he is returning a lot of residue, the soil you're protecting the soil is no-tillage so that you're not disturbing the soil. Um, so you can build up your carbon bringing more carbon through cover crops, other things like that. If you have animal, when you're, you know, for fear of prescribed grazing and therefore, you know, you're, um, adding more manure to your

00;59;32;04 soil that way and gain religious about, uh, how, uh, how much carbon you're removing, uh, from grazing and things like that, then there's, that is another path that you can also get there through improvement to improve soil health.

00;59;47;22 [Robert Bonnie]: So I want to, I want to close on one question too, to all of you just about thinking about, uh, we we've talked some about sort of outreach, um, whether it's, um, uh, crop consultants or, or farmer to farmer work, or, uh, Indigo is the business model, this idea of kind of how to do we, we deliver this stuff. Wayne, you worked for NRCS wonderful agency, but NRCS, isn't going to be able to do this all on its own. It's

01;00;18;10 not going to be able to deliver the technical assistance, uh, in of itself, We're going to need to figure out how do we tap into those existing networks? How do we, um, how do we, you know, whether it's businesses or, or state departments of agriculture or farmer to farmer, um, each year, thoughts on, how do we think about this in policy? How do we, uh, uh, take advantage of those existing networks and build on what's already out there without thinking, this has to be just an NRCS or just a government thing.

01;00;49;10 Fred, let me, I'll, I'll start with you.

01;00;52;25 [Fred Yoder]: Well, great point. And I think it's going to vary depending on where you are located and some States, uh, the extension is very, very active. I think they would play a significant role in this other places. I think there's a lot of certified crop advisors that would be very good to do this. NRCS has great people, but they don't have the manpower to do this. You're right. It needs to be contracted out to the ones that can do this. The other part is, and when you had a lot of great points about that, there is no one size fits all. I mean, you can, if you want to go to make it more

01;01;23;22 efficient, you can, you can do satellite imagery. You can do, uh, uh, based on practices and things like adage. The sky's the limit. There's, there's not a one size fits all here. I think you're going to have to have all the tools in the toolbox. So depending on where you are, you call on the, your extension folks, you call on NRCS folks, you call on, on CCA folks, you call on, um, uh, the soil and water conservation folks. Uh, there's lots of different strengths, but there's also different weaknesses wherever you go.

01;01;51;20 But the main thing is, uh, the assessment of what you have in your community and figure out which tools you need and, and, and, and do cause. But I think every single farm can benefit from this. Every single farm can be more productive if they supply, if they get into climate smart agriculture and, and help produce a new sequestration of carbon, we can all win with this, but there may be different ways to do it.

01;02;17;03 [Robert Bonnie]: Laura, thoughts from you on how we think about outreach from a policy perspective?

01;02;24;10 [Laura Wood Peterson]: Yeah, I think it goes back to the leadership that Senator Sprott and stabbing out, providing and growing the community. Um, there's existing infrastructure, as you've mentioned, you know, there are conservation districts on everything. Fred said, I really agree with, um, there's also businesses outside of ag that can be brought into this conversation and of course the international community. So, um, it, there's no silver bullet to climate change in any industry and it's, it's the same brag it's going to be unique. Um, and farmer to farmer is also really

01;02;56;00 critical. We learn a lot from our fellow farmers and ranchers. So the work of the soil health Institute, the work of all the, um, the different academics and NGOs in this space who are important. So I really think it takes everyone and, and I'm really happy to see the bipartisanship that is really seeking to grow this community to, to as big as we can.

01;03;16;13 [Robert Bonnie]: Wayne, I'm going to let you close us out on this question or how do we, how do we design policy back in DC that, that unleashes the creativity and, and the entrepreneurship and these in these networks out there?

01;03;31;30 [Wayne Honeycutt]: Yeah. You know, um, I guess I see it from a couple perspectives. Uh, one is, I feel like that it's really critical. You asked me earlier about research, what research policies are there, but I feel like it's equally important that we look at the adoption level of policies and really integrate them, really integrate, uh, the agencies, the different entities, uh, that are responsible for those two sides and make sure each of them is at the other one's table when they, when they're

01;04;03;19 designing the research or when they're developing the adoption policies. And, uh, there are, I really feel like that the, because farmers are historically, um, so I'm kind of driven for through independence and, uh, being an independent manager in and the owner of their business. Um, I just do feel like that, uh, to the extent all of this can be done on a voluntary basis, voluntary policies and not regulatory

01;04;33;27 policies, uh, that it will have by far the greatest success.

01;04;38;12 [Wayne Honeycutt]: And I really feel like that there are opportunities for incentivizing even beyond, uh, financial assistance, uh, for them, for adopting these. I really feel like that is kind of a, more of a information assistance of, of showing them how, when you increase carbon in your soil, this is what it means for building drought resilience. And so people now will then adopt it as a risk management tool essentially, uh, you know,

01;05;08;00 for, for their business. Uh, the same type of thing is that also impacts yield stability, uh, impacts the economics as Fred has described, uh, it even impacts of their pest suppression when you enhance soil health and some of these same practices that are used to build carbon, you can essentially increase bio diversity and reduce pathogen, pathogen pressure. Um, and so there are those types of opportunities. And I feel

01;05;36;16 like that to the extent we can really quantify things like those yield stability benefits. And now incorporate that into things like our, uh, um, our risk management approaches, whether it would be for example, a reduced crop insurance premium, or a farm loan interest rate for somebody that now demonstrates they are a lower risk because their yield is more stable because they've adopted these practices. Uh, and so to the extent we can quantify those, that type of information and incorporated into those types of policies. And

01;06;07;28 those I see as really additional, uh, beneficial in sentence, uh, that could really help with the adoption of these systems that are actually benefit the environment and therefore all of the public.

01;06;20;16 [Robert Bonnie]: Well, I want to thank each of you for joining, uh, joining us today as is a great discussion. Uh, I want to thank you for allowing us to take an additional, uh, 10 minutes of your, of your time this afternoon. I think it was worth it. Um, I would encourage everybody to subscribe to the BPC YouTube channel. We're going to have more, um, uh, webinars around natural climate solutions. A couple of weeks, we're going to have one around, uh, natural climate solutions, economic recovery in rural America, uh, that I think will be of interest to folks as well. Um,

01;06;53;20 Fred, Laura, Wayne, thank you so much for joining us today and thanks to everybody for listening in, have a great day.

Share

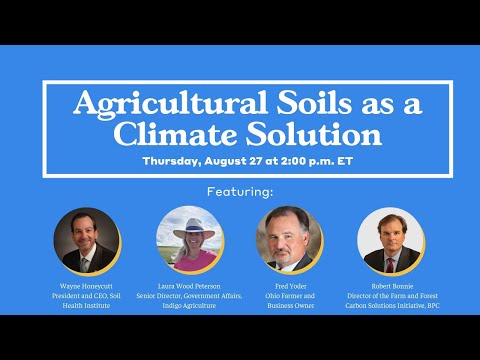

U.S. agriculture has an important role to play in addressing climate change. There is growing interest in the potential of agricultural soils to sequester carbon through a variety of conservation practices while providing a host of co-benefits. This webinar will address the science behind soil carbon, how farmers are adopting new practices, and the business case for climate-smart agriculture. This will be the first of a series of webinars on the policy and practice of natural carbon solutions.

Featured Participants:

Wayne Honeycutt

President and CEO, Soil Health Institute

Laura Wood Peterson

Senior Director, Government Affairs, Indigo Agriculture

Fred Yoder

Ohio Farmer and Business Owner

Moderated by:

Robert Bonnie

Director of the Farm and Forest Carbon Solutions Initiative, BPC

More Upcoming Events

Sign Up for Event Updates

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.

BPC Policy Areas

About BPC

Our Location

Washington, DC 20005