Case Studies: How Partnerships Can Help Fix America’s Water Infrastructure

The United States has a litany of water infrastructure issues, from years of deferred maintenance to emerging dangerous contaminants. An estimated $744 billion will be needed over the next 20 years for capital improvements, repairs, and maintenance across drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems. Meanwhile, according to some studies, up to half of the water workforce?including operators and engineers?have reached retirement age.

Also looming overhead is the risk of a failure at any stage of a water system’s operation, which can be devastating and has the potential to create a public health crisis. Solving these problems, without jeopardizing the affordability of water services, is a delicate balance. Further complicating the United States’ water landscape, there is a sharp divide between the capabilities of large and small systems to meet these many challenges.

Challenges for

Small Systems

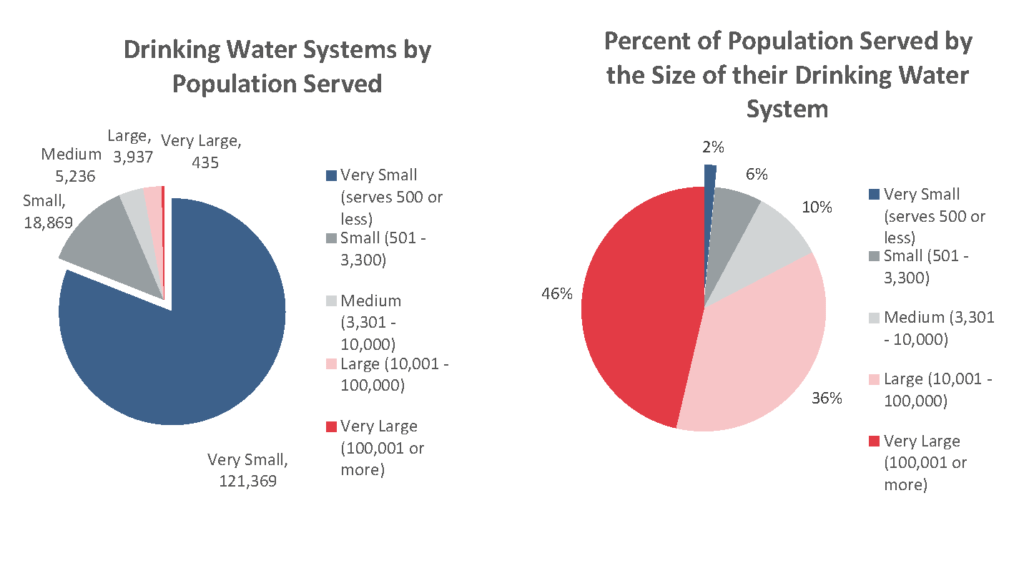

The United States is served by approximately 150,000 public drinking water systems and 16,000 public wastewater systems. While 94 percent of drinking water systems are small or very small, serving 3,300 or fewer households, they only serve 8 percent of the population. Similarly, 79 percent of wastewater systems serve only 10 percent of the population.

With a smaller population base, spread across a large area, the average small system has twice as many water mains break as the average large system. Small systems are also twice as likely to have a health-based drinking water violation. Yet, consumers of smaller, rural systems end up paying an average of three to four times more than their urban counterparts for water and wastewater services. With a smaller rate base to spread out costs, small systems inevitably are required to charge more per-household in order to complete necessary upgrades and to adopt the latest technologies.

Challenges for

Challenges for

Large

Systems

The vast majority of the U.S. population is served by larger systems. For wastewater, 560 systems service more than 205 million people, or 90 percent of the served population. On the drinking water side, nearly 4,400 systems serve 82 percent of the population, with nearly half the population served by the largest 435 systems.

For cities and towns with rapidly expanding populations, each new housing development places new strains on the systems, which must be built out to serve them. Cities with shrinking populations have their own unique problems. For example, large systems operating in cities like Detroit, New Orleans, and Pittsburgh were designed for a larger population than they currently serve. But regardless of the population, the operations and maintenance costs of these systems remain relatively the same. When the population shrinks, those costs are spread across fewer people, leading to disproportionately higher bills.

While a smaller percentage of large systems have compliance issues, any one failure can impact a far greater number of people and become a public health crisis. For example, in 1993, Milwaukee experienced an outbreak of chlorine-resistant Cryptosporidium which contributed to 400,000 illnesses and 69 deaths, in what is still considered the worst waterborne disease outbreak in U.S. history.

Finding

Solutions

Large or small, each drinking water and wastewater system is different, using a variety of technologies and serving different populations, from large metropolitan areas to small farming communities. While each system shares a common goal?protecting the public’s health and the environment?they vary by geography, water source, geology, and regulatory requirements. The extreme disparity between the largest and smallest systems, along with the sheer volume of systems, combine to create a unique set of barriers to “fixing” America’s water infrastructure.

However, one small system (Avon Lake, Ohio) and one larger system (Loudoun County, Virginia) have developed innovative solutions to their challenges. The case studies that follow demonstrate how both large and small systems can innovate, and use partnerships and regional solutions to improve service and distribute costs.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.