Why Inland Waterways Matter for More than Just Fishing

As we await details on the Trump administration’s infrastructure plan, national attention has largely been focused on land infrastructure such as roads, bridges, airports, and railways. In order for the administration’s infrastructure plan to adequately address the needs of our growing freight transportation network, however, it must include the rivers, locks, and dams that form our inland waterway system. Like the rest of our nation’s infrastructure, this system is in dire need of repair and modernization.

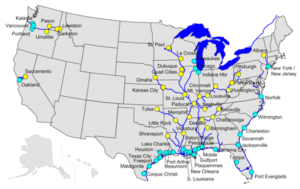

America’s rivers are far more than recreational centers. They comprise 12,000 miles of navigable waterways with 241 locks and carry nearly 600 million tons of freight each year?14 percent of all domestic freight. This network directly serves 38 states, facilitating crucial economic exchanges by connecting rural communities to economic hubs and coastal ports.

The inland waterway system’s locks and dams act as elevators for cargo ships, allowing them to traverse rivers with differing water levels and making our many rivers navigable. Yet 60 percent of the locks in the system are more than 50 years old and were only built for a 50-year lifespan. These older locks are often too small to accommodate current cargo levels and, as they age, they often fail, causing delays throughout the system. Between 2000 and 2014, the average delay per lock nearly doubled from 64 minutes to 121 minutes. Across the system, 49 percent of vessels experienced delays in 2014. These delays take a toll on our economy, but can be addressed through adequate infrastructure investment. To help protect rural industries, facilitate international trade, and improve economic efficiency, inland waterways must be included in any proposed infrastructure plan.

Why Inland Waterways Matter

Inland waterways complement both highways and railways, together providing a national multimodal freight transportation system. In a study by the University of Tennessee and the University of Kentucky, experts found that inland waterways were responsible for nearly 550,000 domestic jobs, $29 billion in income, and $125 billion in aggregate economic output in one year alone.

Inland waterways provide a low-cost transportation mechanism for farmers to reach both domestic and international markets. In 2015, 72 percent of U.S. agricultural exports and 60 percent of domestic grain were transported on these waters. Thanks in large part to the inland waterways, U.S. agricultural exports will contribute $21.5 billion to the U.S. balance of trade this fiscal year. This helps support one million jobs on and off the farm, and provide farmers with 20 percent of net farm income.

These trade benefits do not just extend to agriculture. In 2014, 72 percent of goods intended for international trade were moved via water, compared with 10 percent by truck, 5 percent by rail, and less than 1 percent by air. For example, inland waterways are responsible for shipping over 22 percent of domestic petroleum. As the United States continues to expand its oil exportation, inland waterways will provide a crucial linkage to reaching international markets.

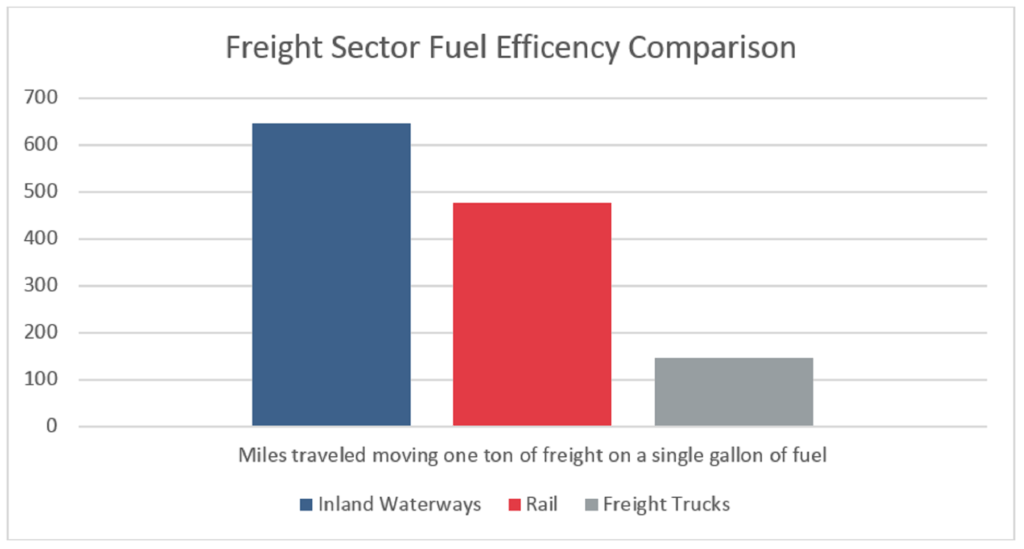

These waterways are also the most fuel efficient form of freight transportation. Railroads are 26.3 percent less fuel-efficient than inland waterway freight transport and freight trucks are 77.6 percent less efficient. Shippers, and ultimately consumers, save $20.37 per ton of cargo, or $12.3 billion annually, on freight carried on these inland waterways as compared to other modes of transportation.

Without the inland waterways system, the country would need to increase truck freight on rural interstates by 14 percent, which would require approximately 2 inches of additional asphalt to maintain the nearly 120,000 lane-miles of rural interstate. Not only is inland water crucial to international trade and rural farmers, but it is cheap, fuel efficient, and helps reduce infrastructure strain on our nation’s road and rail systems.

Inland Waterway Needs

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, costs attributed to delays reached $33 billion in 2010 and are projected to rise to $49 billion by 2020. Estimates about the amount of funding needed to repair the inland waterway system range from $8.7 to $13 billion by 2020. Our system of locks and dams, built largely from the 1930s to the 1950s, is beginning to outlive its useful lifecycle, and desperately needs repair and modernization.

Current Funding Streams

The Army Corp of Engineers manages 11,000 miles of fuel-taxed inland waterways, covering 92 percent of commercially active waterways. On these waterways commercial operators pay a 29 cent tax on barge fuel that is deposited to the Inland Waterways Trust Fund (IWTF). This trust fund pays for 50 percent of construction and rehabilitation costs of the waterways, including locks and dams, with the other 50 percent being appropriated from general revenues. In 2015, the inland waterway fuel tax was raised 9 cents to the current 29 cent mark due to a depletion of the trust fund caused by an increased demand for construction projects and delays in the construction of the Olmsted lock and dam, a high priority project on the Ohio River authorized in 1988 that has since become the largest and most expensive inland waterway project in the United States.

Operation and maintenance (O&M) costs are fully paid for by the federal government through the Army Corps of Engineers’ Civil Works Mission budget. Federal appropriations for inland waterways have nominally increased over the past 40 years, but have fallen in real terms. The Army Corps of Engineers spending on civil works (which includes inland waterways) has shrunk from 0.16 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1962 to a low of 0.04 percent in 2017. However, in fiscal year 2016, Congress funded the Army Corps of Engineers’ Civil Works Mission at near-record levels with $759 million, and dedicated $405 million for five IWTF projects. While this increase is a step in the right direction, it is not nearly enough to account for the years of underinvestment.

What Can Be Done

To meet the overwhelming need of our inland waterways, four possible modifications have been suggested:

1. Delays plague inland waterway transit, but there is no standardized system to account for the causes of delay. Data pinpointing where delays occur, why they occur, and for exactly how long could be useful for a standardized review of the system. This standardization would allow for more targeted funding for both maintenance and construction to address the most costly and burdensome bottlenecks in the system. This could also be part of a broader effort to develop comprehensive, life-cycle asset inventories of all national infrastructure assets, which would enable public agencies to more strategically manage their infrastructure needs.

2. Federal funding for inland waterways comprises 90 percent of all system funding, compared to 25 percent for highways, and virtually no general revenue support for freight rail. As such, the burden of an aging system falls entirely on the federal government. Groups such as the Upper Mississippi River Basin Association, formed by the governors of Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri, are looking at ways to alter the current cost sharing arrangement to inject more money into the system.

3. The current funding debate is centered around construction and rehabilitation of specific high-risk locks. The Army Corp of Engineers evaluates the total risk exposure of certain locks and then directs appropriated funds from the IWTF for the construction and rehabilitation of the highest profile projects. The IWTF is, however, limited in that it only has $867 million worth of funds and can only pay for construction or large-scale rehabilitation projects. In 2016, only five projects received funding, with 66 percent of funds going to the Olmsted lock and dam. This leaves O&M costs for the hundreds of other locks in the system competing with construction projects for funding from federal general revenues. Advocates fear that without a dedicated funding stream for O&M, the Army Corps will defer individual repairs until they reach a $20 million cost threshold, which classifies them as a rehabilitation project and qualifies them for IWTF funds. This deferment strategy is a less cost effective option for taxpayers and one that can worsen system delays. One possible solution offered to this problem is applying user fees at specific locks. By dedicating revenues from users to maintenance, a more efficient and effective system could be created where repair funds are directed to preemptively fix problems that cause long delays. These funds could be deposited into a new trust fund or into a reformed IWTF that would be able to fund both construction and O&M. Many see this as the only way to raise enough sustained funding to pay for the system and make it less reliant on the year by year budget of the Army Corps of Engineers. Yet this program is not without its critics. The Waterways Council Inc.?a group representing shippers and receivers of bulk commodities, waterways carriers, ports, shipping associations, agriculture producer groups, and other groups involved in waterway advocacy?has called this process “highly predatory” and threatening to the economic viability of the transportation system. Many in the industry fear that a user fee will hurt inland waterways and direct traffic to other forms of freight shipping.

4. In the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014, Congress approved a public-private partnership (P3) pilot program to “evaluate the cost effectiveness and project delivery efficiency of allowing non-federal pilot applicants to carry out authorized water resources development projects.” This was an attempt to find ways to leverage private dollars to help finance the construction, improvement, and maintenance of various locks and dams on the inland waterway system. These P3 projects, however, face several key challenges: First, IWTF funds cannot be used for future deposits for project-specific purposes, which may be needed to repay the private partner. Secondly, the scoring guidelines outlined in OMB Circular A-11 would classify any availability payments for a P3 lease as a capital lease and score 100 percent of their cost to the federal agency in the first year of the contract, a sizable burden on an already cost-strapped program. Finally, federal laws currently ban user fees that could be utilized to pay private investors. P3 projects such as the Illinois Inland Waterway project that would have a private company design, rehabilitate, finance, and maintain a system of eight locks on the Illinois River are constrained by current law. By changing these constraints private sector money could be inserted into the system, allowing for investments to be directed to aging locks.

Moving Forward

Despite being such a vital link in the movement of goods, the inland waterway system is at risk of further deterioration. As the current system funds projects on an ad hoc basis, the locks and dams continue to age and become more likely to fail. There are a number of potential solutions for helping meet the system’s massive needs and more sustainably operate and manage them in the future. As a national infrastructure plan emerges, finding ways to improve this important part of the freight transportation system should be a key bipartisan objective.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.