Update on Iran’s Nuclear Program

Summary

- Iran has failed to convert over 1,200 kilogram of 3.5 percent enriched uranium into uranium oxide, as required by the Joint Plan of Action.

- In a separate negotiating track with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Iran continues to refuse to provide information on its alleged past research into military nuclear technology.

- Iran continues to refuse to abide by parts of its legally-binding Safeguard Agreement with the IAEA.

- This pattern of minor infractions serves to both set a precedent and probe the international community’s willingness to punish transgressions.

Analysis

The latest report1 on Iran’s nuclear program by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) suggests that Iran continues to test the boundaries of the current diplomatic process to address its nuclear program. Tehran might be cooperative in talks with the P5+1 but is thwarting attempts by the IAEA to reveal the extent and nature of Iran’s past nuclear work and safeguard its ongoing nuclear activities. Moreover, although Iran is required to cap its production of 3.5 percent enriched uranium durin the interim deal, known as the “Joint Plan of Action” (JPA), it maintains a stockpile significantly larger than when the JPA went into effect.

Continued Stonewalling on PMD

As discussed in a previous analyses, although much attention has been focused on negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 countries there has also been a parallel diplomatic track going on between Iran and the IAEA. Called the “Framework for Cooperation” (FC), the IAEA’s “approach [is] aimed at ensuring the exclusively peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear programme” and gaining a better understanding of Iran’s past nuclear research, particularly on the so-called possible military dimension (PMD). Under the FC, the IAEA and Iran agreed to a set agenda of IAEA concerns for Iran to address and a timeline for doing so. Since November 2013, the FC has gone through three rounds, with a total of 17 issues raised: five in the first round, seven in the second, and five in the third.

Yet, two of those issues remain unresolved since September 2014. Both of these unresolved issues have to do with Iran’s past nuclear research: explaining Iran’s experimenting withhigh explosives and researching neutron transport calculations. However, the fourteen issues on which Iran has been compliantare unrelated to the possible military dimension of its nuclear program, focusing instead on current and ongoing activities.

In the almost half year since the September IAEA report, nothing has changed on addressing the outstanding items. As laid out in the most recent reports, despite multiple meetings between Iran and the IAEA, no progress has been made on the outstanding items. Iranian negotiators have not been forthcoming on providing a civilian justification for their work in the areas in question.

Shunning Safeguards Obligations

In December 2014, Iran announced that it would build in the next year a second nuclear reactor at its Busher facility?where it currently operates an electricity-generating light water reactor. Although Iran is legally obligated to share design plans with the IAEA as soon as the decision is made to construct any new nuclear facility, it has refused to provide those plans and essentially told the IAEA it would comply with its safeguards obligations when and how it feels inclined to do so.

By signing onto the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 1968, Iran became legally obligated to execute a Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA. The Agreement, which Iran signed in 1973, granted the IAEA the right to monitor and verify Iranian nuclear activity and compliance with the NPT. This included a requirement that states give the IAEA 180 days advance notice before they begin construction on a new nuclear facility. This was designed to give the IAEA enough time to analyze the facility’s plans and come up with a safeguards regime for it. In the 1990’s the IAEA realized that six months was not enough time and updated the term to require notification as soon as a state decides to construct a new facility.

Even though it had agreed to this change to its Safeguards Agreement, in 2007 Iran notified the IAEA it would no longer honor it. Thus, when the IAEA wrote to Iran seeking design information about the new nuclear reactor announced in December 2014, Iran refused, replying only that, “more information, when available, will be provided to the Agency in due time.”

Such unilateral decisions about which parts of the Safeguards Agreement to comply with are clearly illegal. The United Nations Security Council, in resolution 1929, “reaffirms that?Iran’s Safeguards Agreement?cannot be amended or changed unilaterally by Iran, and notes that there is no mechanism in the Agreement for the suspension of any of the provisions in the Subsidiary Arrangement.” Yet, Iran continues to ignore this legal obligation, much like it does the requirement, contained in the same UNSCR resolution as well as four others, that it “suspend all enrichment-related activities” until it can instill “confidence in the exclusively peaceful purpose of its nuclear programme.”

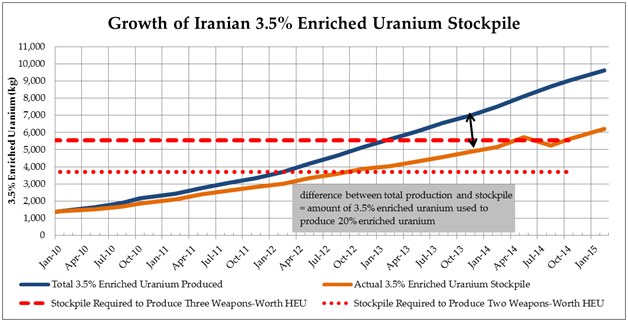

Stockpile Overload: Potential JPA Infractions?

The JPA, initially negotiated in November 2013 and implemented on January 20, 2014, was meant to be a six-month confidence building measure, designed to give both sides time to negotiate a comprehensive deal without the pressure of additional Iranian nuclear advances or international sanctions. That window proved insufficient and, in July 2014 and again November 2014, the P5+1 and Iran announced extensions of the JPA, now slated to expire on June 30, 2015. Yet, it appears that Iran has failed to comply with a term of the meant to ensure that its stockpile of 3.5 percent enriched uranium did not grow at all during the deal’s term.

Specifically, Iran agreed to “convert to oxide UF6 newly enriched up to 5percent during the 6 month period.” Whereas UF6 is a gaseous uranium compound used for enrichment, uranium oxide (or UO2) is a metallic compound used in nuclear fuel rods. Although UO2 can be turned back into UF6 and enriched further that step adds additional time to a potential breakout attempt.

In order to comply with this provision, Iran had to build a new facility?the Enriched UO2 Powder Plant (EUPP)?to handle the conversion. The plant was not completed until May 2014, five months after JPA went into effect, did not begin operations until July 2014, at the very end of the initial the period, and it was August before 1,500 kilograms of 3.5 percent enriched UF6 were not converted into UO2, after the first six months had elapsed.

Since then, Iran has fed another 1,200 kilograms of 3.5 percent enriched UF6 into the EUPP?for a total of 2,720 kilograms?per its requirements under the extended JPA. The problem, however, is that Iran has produced over 1,400 kilograms of 3.5 percent enriched UF6 in that same time. Indeed, whereas Iran had a stockpile of close to 5,000 kilograms of 3.5 percent enriched UF6 in January 2014, when JPA went into effect, today it has nearly 6,200 kilograms. This excess stockpile not only provides Iran with more nuclear materials in the case of a breakout but also marks a violation of the text of the JPA.

Conclusion: Testing Resolve

Iran’s pattern of minor infractions and constant unilateral interpretation of its legal obligations has clearly annoyed the IAEA. Several times in its latest report, the IAEA repeats that Iran “has not provided any explanations” for its PMD work, that IAEA safeguards obligations are “legally binding,” and that “full implementation of Iran’s obligations is needed in order to ensure international confidence in the exclusively peaceful nature of its nuclear programme.”

Though it may seem as if the IAEA is quibbling over minor issues?past research and plans for facilities that may never be constructed? with little bearing on Iran’s current nuclear breakout capacity, Iran’s behavior impacts the ability to reach a comprehensive agreement that would prevent a nuclear-capable Iran and, were there to be such a deal, sets a precedent for how Iran would approach it. The less willing Iran is to come clean about its previous research into nuclear weapons technology, the less confident the P5+1 can be that Iran is negotiating or entering into a nuclear deal in good faith. The less the IAEA knows about Iran’s nuclear work, the less effective any additional verification measures adopted under a comprehensive agreement will be. And the more often Iran is able to renege on its legal commitments, the more it sets the expectation that such seemingly small violations are run-of-the-mill. And the greater the expectation for transgressions, the greater tolerance there is for them.

For this reason, the test of any comprehensive deal will be the ability to detect and respond to any similar transgressions of that agreement. As laid out, however, by the Bipartisan Policy Center’s (BPC) Iran Task Force, an acceptable comprehensive agreement with Iran will require, no matter the contents of a deal, and no matter how long its duration, on continued enforcement and vigilance from the United States and its partners. Vigilance will come, in part, from monitoring Iran’s compliance, and will require continued support for the IAEA’s inspections efforts. It will also be incumbent upon the international community to demonstrate credibly to Iran’s leaders that there will be consequences if they attempt renege.

Additional details and highlights from the IAEA report include:

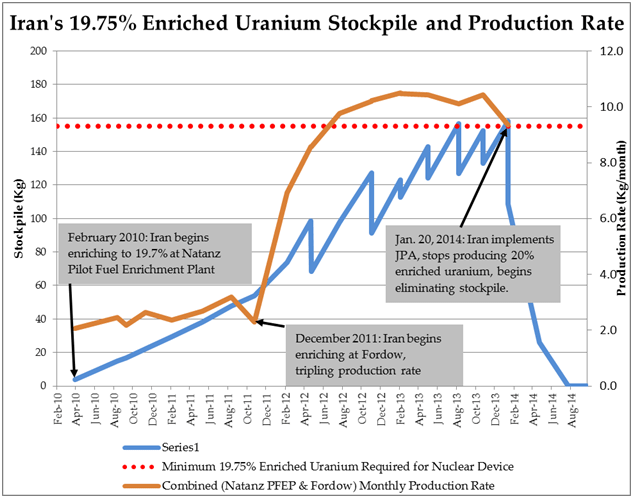

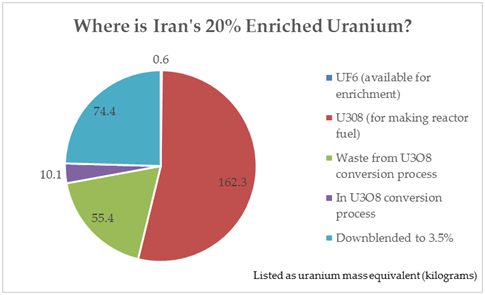

Production of 20 Percent Enriched Uranium Ceases, Stockpile Gone?

- Per JPA, enrichment to 20 percent halted at Natanz Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant and Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant.

- Centrifuge cascades used to enrich to 20 percent at each site disconnected;

- IAEA installed additional safeguards to monitor that they remain disconnected.

- Total 20 percent enriched uranium produced since production began (Feb. 2010): 302.7kg.

- Actual stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium: 0kg.

- JPA specifies that Iran must eliminate its entire stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium.

- Half to be turned into reactor fuel;

- Half to be downblended to 3.5 percent enrichment level.

- Total of 228kg removed for oxidization (production of reactor fuel):

- 74.4kg downblended to 3.5 percent since Nov. 2013.

- JPA specifies that Iran must eliminate its entire stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium.

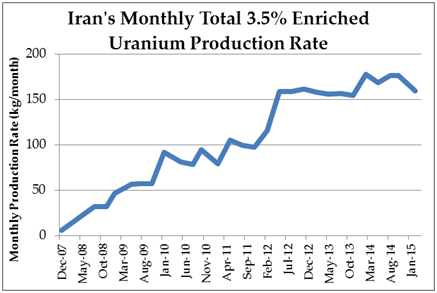

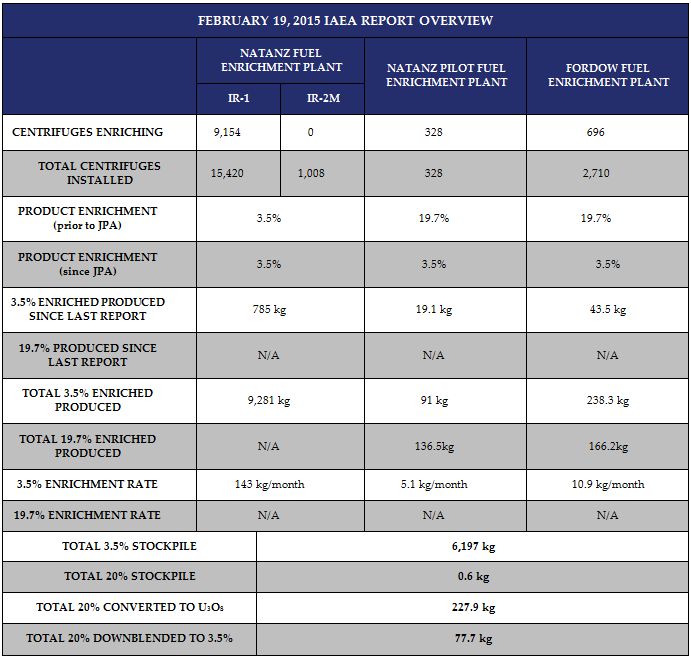

?But Production of 3.5 Percent Enriched Uranium Jumps

- Facilities enriched to 20 percent switched over to making 3.5 percent enriched uranium.

- There are now three facilities enriching to 3.5 percent:

- Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant;

- Natanz Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (previously producing 20 percent enriched uranium);

- Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant (previously producing 20 percent enriched uranium).

- There are now three facilities enriching to 3.5 percent:

- Total production drops slightly, remains at pre-JPA levels: 159kg/month.

- Lower than in Feb. 2014 when it was at record high of 177.8kg/month.

- Natanz production rate of 3.5 percent drops to 143kg/month.

- Previous reporting period: 160kg/month.

- Highest recorded rate: 161kg/month (Nov 2012).

- Natanz PFEP production rate of 3.5 percent up slightly to 5.1kg/month.

- Highest recorded rate: 5.2kg/month (May 2014).

- Fordow 3.5 percent production rate of 3.5 percent down to 11kg/month.

- Highest recorded rate: 16.3kg/month (Feb. 2014).

- Total 3.5 percent enriched uranium produced since production began (Feb 2007): 9,612kg.

- 593kg produced since last reporting period:

- 530kg at Natanz;

- 19kg at Natanz PFEP;

- 44kg at Fordow.

- 593kg produced since last reporting period:

- Actual stockpile of 3.5 percent enriched uranium as of November 2014: 6,198kg.

- 3,400kg used for enrichment to 20 percent or turned into uranium oxide for use in reactor fuel.

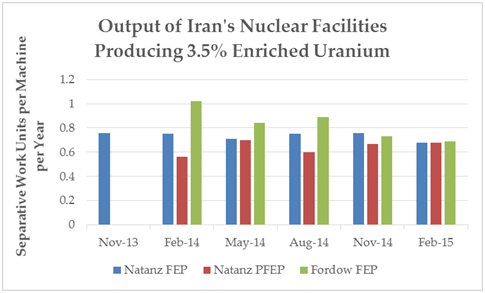

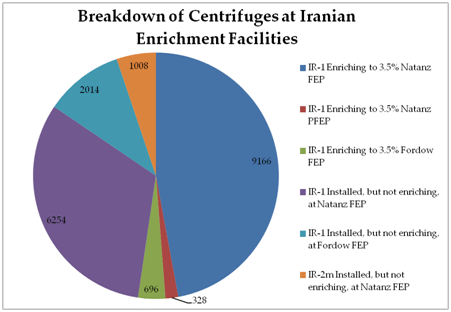

Iran Squeezes More out of IR-1 Centrifuges, Continues Researching New Models

- Per JPA, number and type of centrifuges largely unchanged at all enrichment facilities.

- Natanz FEP:

- 16,428 total centrifuges installed (unchanged):

- 15,420 IR-1 centrifuges;

- 1,008 IR-2m.

- 9,156 IR-1 centrifuges operating:

- Same as previous reporting period.

- Equal to number operating in early 2013/late 2012.

- All operating centrifuges are IR-1 model.

- Output of operating centrifuges drops to .68 SWU/machine/year.

- Previous reporting period: .76 SWU/machine/year.

- 16,428 total centrifuges installed (unchanged):

- Natanz PFEP:

- 328 IR-1 centrifuges installed and operating (unchanged).

- Output of centrifuges producing 3.5%: .68 SWU/machine/year.

- Highest reporting period: .70 SWU/machine/year (May 2014).

- Fordow FEP:

- 2,710 IR-1 centrifuges installed (unchanged).

- Facility accommodates 2,976 centrifuges.

- 696 IR-1 centrifuges operating (unchanged).

- Output of centrifuges producing 3.5 percent: .69 SWU/machine/year.

- Highest reporting period: 1.02 SWU/machine/year (February 2014).

- 2,710 IR-1 centrifuges installed (unchanged).

- Research and development of advanced centrifuges continues.

- Iran experimenting with:

- 168 IR-2m centrifuges;

- 199 IR-4 centrifuges;

- 1 IR-5 centrifuge;

- 13 IR-6 centrifuges;

- 1 IR-8 centrifuge.

Fuel Conversion and Fabrication

- Facility for conversion of 3.5 percent uranium hexafluoride into uranium oxide finally completed.

- Iran has oxidized 2,720kg of 3.5 percent enriched UF6.

- During this same period, Iran has produced over 3,300 kilograms of 3.5 percent enriched UF6.

- Given the JPA requirement to cap its production, Iran has at least a 600 kilogram surplus.

- Conversion of 20 percent enriched uranium hexafluoride into uranium oxide and fuel plates for Tehran Research Reactor continues.

- Total 20 percent enriched uranium fed into conversion process: 228kg.

- Total 20 percent enriched U3O8 produced: 162.8kg.

- 55.4kg 20 percent enriched U3O8 produced in waste.

- Means that about another 10kg 20 percent enriched U3O8 are still being processed.

- Of the 20 percent enriched U3O8 produced, 90.6kg has been used for fuel production.

- Total of 33 fuel assemblies for TRR have been produced.

- Of these, 30 transferred to TRR.

- Represents over a decade worth of fuel for TRR.

- IAEA verifies no reconversion of U3O8 into UF6, a possible sign of breakout, currently ongoing.

Heavy Water Reactor

- Per JPA, no work has taken place at Arak Heavy Water Reactor since last report.

Framework for Cooperation

- Iran has failed to provide complete and adequate answers to two other PMD issues raised in the third round of the Framework for Cooperation:

- Information with the Agency with respect to the allegations related to the initiation of high explosives, including the conduct of large scale high explosives experimentation in Iran;

- Information related to studies made and/or papers published in Iran in relation to research into neutron transport of compressed materials.

- Iran has not proposed issues to be addressed in a fourth round of the Framework.

Military Dimensions

- IAEA reiterates that few of its concerns about possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear program have been addressed.

- As a result, report notes that, “The Agency remains concerned about the possible existence in Iran of undisclosed nuclear related activities involving military related organizations, including activities related to the development of a nuclear payload for a missile. Iran is required to cooperate fully with the Agency on all outstanding issues, particularly those which give rise to concerns about the possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme, including by providing access without delay to all sites, equipment, persons and documents requested by the Agency.”

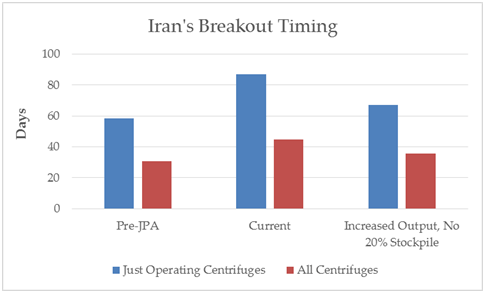

Effect on Timing

Two main variables will determine how much time Iran would need to produce 20 kilograms of 90 percent enriched uranium?the minimum needed for a nuclear weapon?in the near future: its available stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium; and the rate at which its centrifuges are able to enrich uranium. The first has declined to zero as a result of the JPA, increasing breakout timing. But the latest IAEA report shows that the second has increased since the JPA’s implementation, somewhat mitigating the effect of Iran’s loss of its 20 percent enriched uranium stockpile.

- Depending on whether Iran uses just its all of its installed centrifuges or just the currently operating ones, Iran could produce 20 kilograms of highly enriched uranium, enough for a weapon, in between 45 and 87 days.2

- This result is in line with Obama Administration estimates that the JPA would add a month to Iran’s breakout timing.

- In November 2013, prior to the implementation of JPA, that range was 31 to 59 days.

- But continued improvements to Iran’s centrifuges could negate that delay, despite the elimination of Iran’s 20% enriched uranium stockpile.

Time to produce 20kg 90 percent enriched uranium if centrifuge output increases to one SWU/machine/year:

- Using just operating centrifuges: 67 days.

- Using all centrifuges: 36 days.

1 As of latest IAEA report: “Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Board of Governors Report, International Atomic Energy Agency, February 20, 2015 (GOV/2015/15)

2

This calculation assumes Iran uses a three-step batch recycling process to produce highly enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon and is based upon the work of Greg Jones at the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center. Both scenarios assume the use of the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant at its current production rate and drawing upon Iran’s current stockpiles of 3.5% and 20% enriched uranium. For a more detailed explanation, see here.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now