Trump Can Help Property Disposal Move a Little FASTA

With more than 2.8 billion square feet of building space, 42 million acres of land, and about 496,000 structures, the federal government has a considerable array of property under its control. Yet over time, as the goals and directives of federal agencies have changed, properties that were once vital for the government may now be unneeded and costly burdens for an agency to bear. While the obvious solution would be (and, in fact, the federal requirement is) to sell unused or underutilized properties, it typically isn’t that simple. Until the passage of a new law, the disposal of surplus property was oftentimes so time-consuming and costly that agencies largely didn’t bother.

The Federal Assets Sale and Transfer Act (FASTA), which became law in 2016, sought to address these unintended obstacles by establishing a more centralized disposition process. FASTA, sponsored by Reps. Jeff Denham (R-CA), Bill Shuster (R-PA), and Lou Barletta (R-PA), could save the government up to $8 billion by selling or repurposing underutilized, high-value federal properties. Although FASTA enjoyed strong bipartisan support, its implementation is on standby until several key presidential appointments are filled. By nominating a chairperson and six members of the Public Buildings Reform Board, President Trump would greatly facilitate the implementation of FASTA and allow the federal government to begin shedding costly and unneeded properties.

How We Got Here

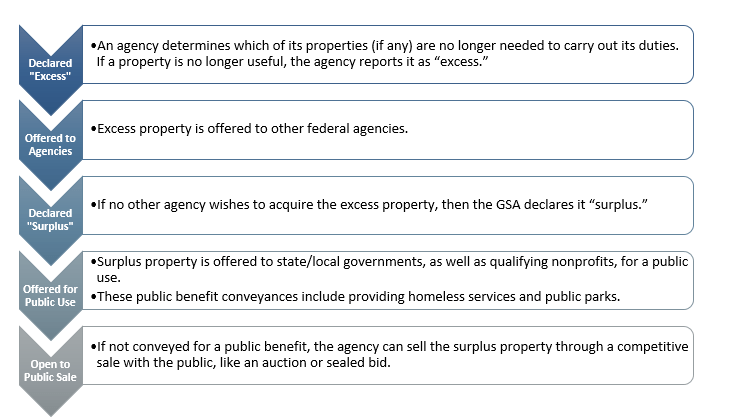

Prior to the passage of FASTA in 2016, federal guidelines on property disposal were outlined by statute. Under a decentralized process, individual agencies identified their unneeded properties and disposed of them in accordance with a series of General Services Administration (GSA) regulations. Figure 1 outlines this process.

Figure

1

: The Pre-FASTA Federal Real Property Disposal Process

Although well-intended, federal agencies lamented that this process was time-consuming and costly. Required screening for conveyances, as well as environmental remediation and historic preservation, could increase costs and extend the duration of the process by months or even years. Furthermore, agencies cited contention between stakeholders as a deterrent for engaging in the disposition process. Competing interests among groups such as historic preservationists, government entities, and vested local interests could thwart agency attempts to dispose of unneeded property. The result was often delayed or cancelled property disposal and agency reluctance to dispose of property altogether.

Lack of congressional oversight and publicly available data on federal property assets were additional issues. The Federal Real Property Profile (FRPP), the GSA’s extensive database, collects annual data on all executive branch agencies’ real property assets. Prior to FASTA, this data was not publicly available. The GSA provided select information to Congress, but only on particular occasions or when requested. Yet perhaps most troubling are claims that the data was inaccurate. Reports by the Government Accountability Office have found that historically some of the agency-reported property data in the FRPP has been incorrect, and that changing definitions for key data terms have created inconsistencies. The lack of transparency, congressional oversight, and reliability of federal property data, in addition to the statutory obstacles of the disposal process, prompted bipartisan support in Congress to pass FASTA in 2016.

FASTA Created a Streamlined Disposal Pipeline

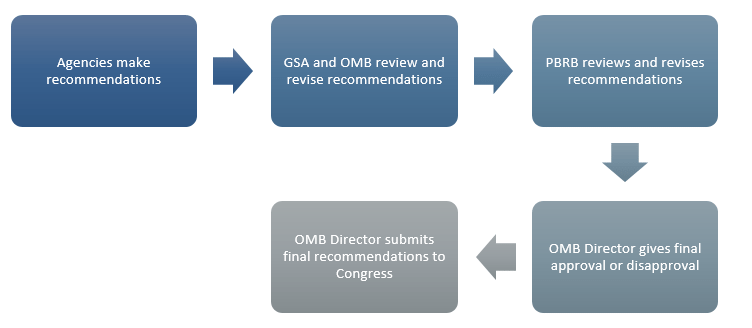

FASTA created a more centralized system for identifying and disposing of unneeded federal property. Whereas previously, individual agencies were solely responsible for identifying which properties to dispose of, FASTA established a streamlined pipeline that reviews federal properties annually. Although agencies continue to play a crucial role in identifying unneeded properties, under FASTA, agencies are now tasked with developing recommendations on how to reduce their unused space and lower operating costs. These recommendations, along with annual reports detailing all their real property assets, are then sent to the GSA and Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Once the GSA administrator and the OMB director receive the recommendations, they jointly review and revise them in accordance with FASTA. Specifically, the administrator and director must devise a set of criteria by which to judge the agencies’ recommendations. FASTA outlines various principles to include in the criteria such as favoring short and long-term cost reductions, maximizing utilization, and lowering energy consumption. Using the criteria, the GSA and OMB edit the recommendations as they deem necessary, after which the OMB director submits them to the newly-formed, independent Public Buildings Reform Board (PBRB).

The PBRB is comprised of six members and a chairperson, all of whom are appointed by the president and must possess relevant professional experience in areas like commercial real estate, space optimization, and community development. FASTA tasks the PBRB with reviewing and editing the recommendations, but the PBRB also has the authority to conduct independent reviews of agency inventories and request any supplemental information. Lastly, the board finalizes its recommendations in a report to the OMB director, who then grants final approval and submits them to Congress. Figure 2 outlines the major steps of FASTA’s disposal process.

Figure 2. FASTA’s Streamlined Federal Property Disposal Process

FASTA Increases Transparency and Encourages Diversity of Input

In addition to addressing some of the main hurdles of the disposal process, FASTA also requires the GSA to manage and maintain a publicly-available properties database on federal assets. The database must include specific information to aid Congress in monitoring agency inventories such as utilization rates and estimated annual operation costs. Exclusions apply for property information or agencies whose disclosure could pose a national security risk.

Another potential benefit of FASTA is that the process involves coordinated and collaborative input from across the federal government. Federal agencies, the heads of the GSA and OMB, and the PBRB all contribute their expertise to the disposal process. The GSA administrator and OMB director jointly review the entirety of the federal government’s properties, which could enable them to see opportunities that may not be apparent at the agency level, such as consolidation of government facilities or an interagency property transfer. Similarly, as an independent board with members who likely have private sector experience, the PBRB adds a new perspective and can highlight opportunities or ideas for properties previously not considered. Although diversity of input could be beneficial, it could also pose setbacks. For instance, conflicting opinions on the disposal process by a prominent individual, such as the OMB director, could completely derail recommendations.

Implementation of FASTA Is Still a Work in Progress

Two years after the passage of FASTA, progress has been slow but steady. Firstly, the GSA made its federal properties database, the FRPP, publicly accessible in December 2017. Earlier that year, Timothy Horne, then the acting GSA administrator, stated that the number of agencies reporting to the FRPP increased from 24 to 51. The GSA also updated its guidelines for federal agency property data reporting. The Federal Real Property Council, which established the guidelines, released its updated reporting standards in its FRPP data dictionary. These efforts by GSA help improve transparency and consistency in data reporting.

Another notable step in FASTA implementation regards funding. In the final omnibus spending bill for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, Congress approved $5 million for the salaries and expenses of Public Buildings Reform Board members and $5 million for the Asset Proceeds and Space Management Fund, which will be used to carry out the recommendations of the PBRB in the disposal process. The House Appropriations Committee recently approved $2 million for PBRB salaries and $31 million for the fund for FY 2019. Currently, the Senate is discussing its appropriations bill for FY 2019, which includes $15 million for the fund.

Comments and efforts by the current GSA administrator, Emily Murphy, suggest that the GSA is committed to FASTA’s implementation. In addition, continued support in Congress is another positive sign for FASTA’s successful implementation. Yet a crucial gap remains: the appointment of all members to fill the Public Buildings Reform Board, a responsibility that falls to the president.

The President Needs to Appoint Members to the Public Buildings Reform Board

Under FASTA, the PBRB’s chair is nominated by the president and subject to Senate confirmation. The administration needs only the input of congressional leadership on the appointments of the board’s six other members. Given the significance of the PBRB in the disposal process, an empty board is a major roadblock to FASTA’s continued implementation and the ability of the federal government to dispose of unneeded property. Currently, it is unclear how the disposal process is operating without any PBRB members. It is also unclear if the Trump administration will pursue its proposed federal property disposition reforms, including (among other things) eliminating public benefits conveyances. Despite these proposals, the PBRB would still play a significant role in the disposal process. Therefore, nominating a chairperson and appointing members to the board remain necessary for FASTA to succeed.

While continued support of FASTA is crucial, the government can do more to reduce operating costs and improve federal property management. As BPC previously noted, federal budget and accounting rules can hamstring the federal government from entering into certain long-term lease agreements and ownership options, despite the potential savings. Although FASTA helps improve the disposition process, further government action is needed to address the regulatory hurdles that discourage agencies from pursuing the most cost-effective property acquisition methods over the long term.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.