Stretching Water Dollars Further

Funding for water infrastructure hasn’t kept up with the costs. In fact, the most recent American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) report card rated America’s water infrastructure a “D” for drinking water and a “D+” for wastewater.

The United States has 14,750 public wastewater systems and 149,501 public drinking water systems?including 99,311 non-community water systems such as schools and hospitals. Due to the sheer number of systems, providing adequate maintenance, repairs, and upgrades across the entire country is a monumental task. Combined, the systems require an additional $105 billion in funding by 2025 just to keep up with the existing maintenance needs. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates the funding gap will be at $655 billion over the next 20 years.

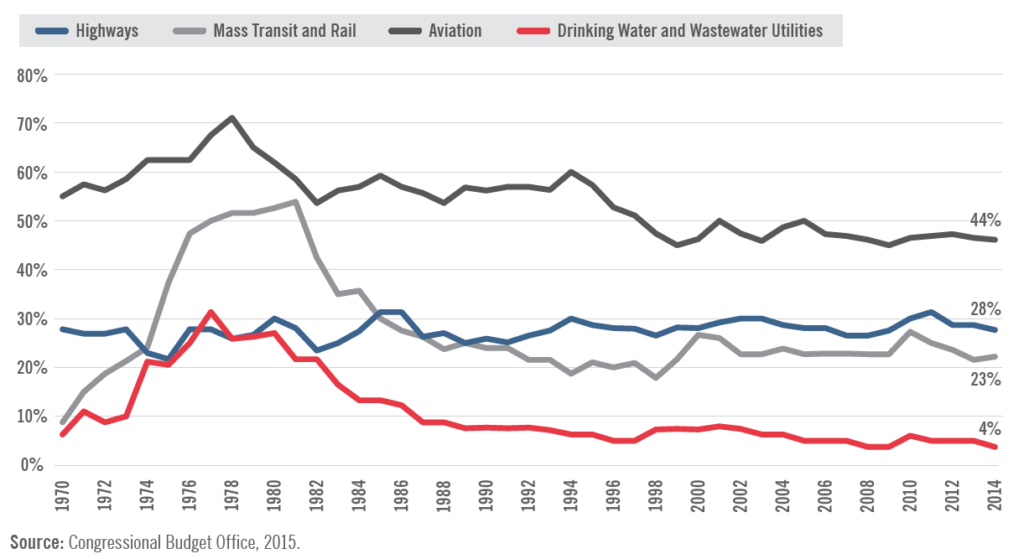

Total Infrastructure Spending, By Sector

Following the initial influx of funding through the establishment of the Clean Water State Revolving Funds (SRFs) in 1986 and the Drinking Water SRF in 1996, federal investment in water infrastructure has steadily declined. As a result, funding for water infrastructure has fallen largely to state and local governments. In 2014, state and local spending on water infrastructure amounted to $104 billion, compared to $4 billion in funding from the federal government. The growing backlog of deferred maintenance is one of the four cost drivers the Bipartisan Policy Center has identified as currently impacting water systems, and that will continue to worsen without targeted interventions:

- Aging Infrastructure ? with decades of deferred maintenance piling up, repairing and replacing our aging infrastructure poses a serious cost to systems.

- Changing Rate Bases ? areas with a rapidly growing population must expand and adapt their water systems, while areas with a shrinking population may struggle to collect rates.

- Regulatory Compliance ? providing clean drinking water and treating wastewater are fundamental to public health, but both are costly and noncompliant systems can face multi-billion-dollar price tags.

- Climate Change ? projections show that climate change will continue to reduce water quality in lakes and rivers, cause more extreme flooding, disrupt freshwater aquifers, and increase the likelihood of droughts.

Despite the challenges posed by shrinking federal investment and rising costs, America’s water systems strive to maintain affordability. As such, many water systems have historically underpriced the services they provide to keep water rates low. In practice, this has exacerbated the problem of aging water infrastructure and is now leading to more rapid rate increases. Since 2010, water rates have increased 41 percent. For 12 percent of Americans, water is now too expensiive, and within the next 5 years that number could triple to 36 percent as rates continue to increase.

Essentially, most water utilities are undercharging their average customers during a period of underinvestment at the federal level. With a limited set of resources, spread across thousands of systems, system operators and policymakers are finding creative solutions to create efficiencies.

Strategies for Stretching Water Dollars

Collaboration and Regionalization

In general, a water system needs technical, managerial, and financial (TMF) capacity to sustainably operate. When a system lacks TMF capacity, it may look to enter into a “partnership” with a neighboring system. These cooperative structures, which can range from informal agreements to a full transfer of ownership, are designed to share resources, reduce costs, and improve water quality. For example, if a small rural system is struggling to find qualified staff, it may need to establish a contracting partnership with nearby systems in order to share a certified system operator.

In North Carolina, for example, one driver of these innovative partnerships has been the Catawba County government, located just 40 miles north of Charlotte. As the University of North Carolina reported, for over 20 years, Catawba County has been entering into revenue sharing agreements with municipal water systems to complete new infrastructure projects. The county also operates a revolving loan program that focuses on economic development projects.

Source: United States Environment Protection Agency, Water System Partnerships Case Studies

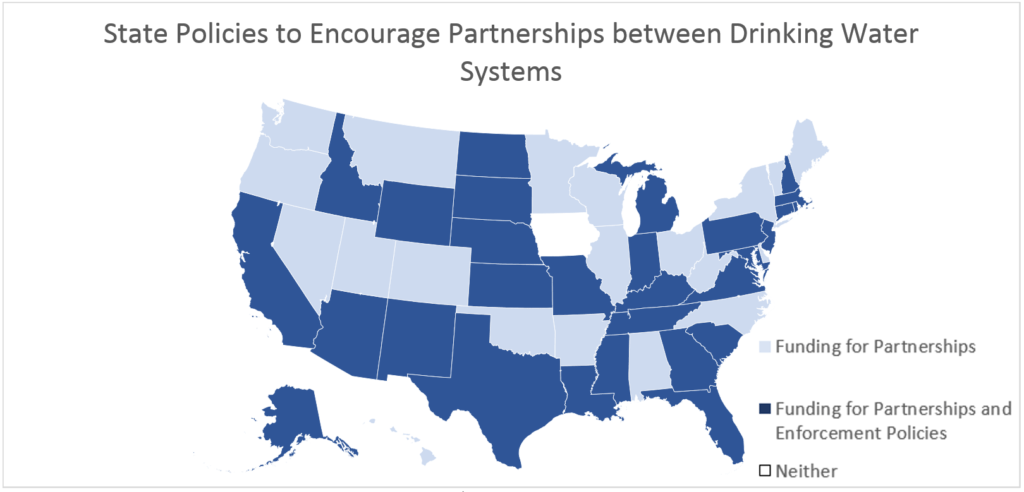

Recently, EPA released a report detailing how each state encourages and facilitates these cooperative structures. Nearly every state (except Iowa) uses priority funding, targeted programs, and/or “enforcement policies” to lead ? or force ? utilities into partnerships. For example, Idaho has a multi-pronged approach that includes the state’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund granting priority to regional water projects, a program that allows systems to share operators, and a statutory rule that requires any newly proposed system to first evaluate obtaining service from a nearby system. “Enforcement policies” to create fewer systems vary around the country, and can range from a statute that allows the state to order a system to restructure after health violations, to regulatory requirements, as seen in Idaho.

Source: EPA, Water System Partnerships, 2017

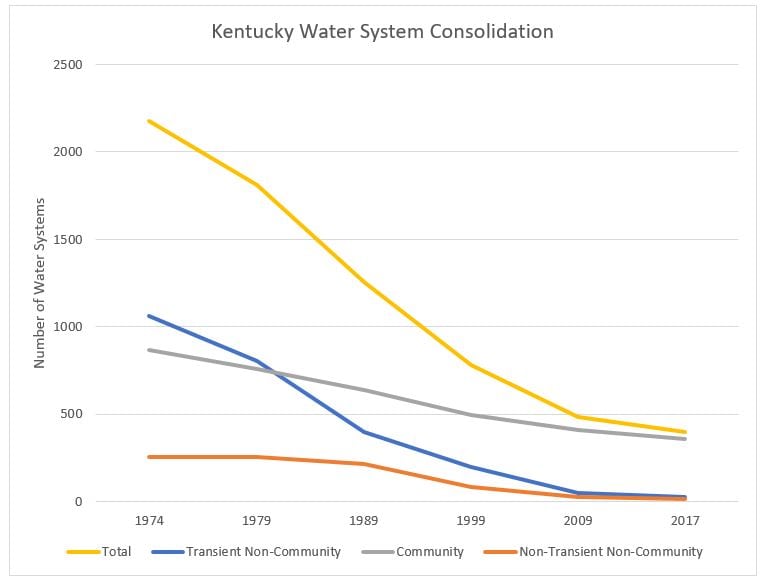

Today, 14 states have regulations in place that require any proposal for a new system to prove that it has first examined the option of connecting to an existing system, but a few states have gone a step further to actively reduce the number of systems. For example, Kentucky has gone from over 2,000 public water and wastewater systems in the 1970s to fewer than 400 systems today. Kentucky achieved this reduction through a combination of policies including targeted regional planning, prioritized funding for regionalization projects, and statutory authority for Kentucky’s Public Service Commission to order the consolidation of water districts (after completing a feasibility study and public hearings). In 2015, California passed a law allowing the State Water Board to require systems to consolidate or receive service from another water system if a system is experiencing chronic water quality failures.

Transient Non-Community Water System, i.e., Resorts, Restaurants, Motels, and Campgrounds Non-Transient Non-Community Water System, i.e., Schools, Businesses, and RV Parks Source: Kentucky Rural Water Association

Consolidating systems is often considered to be one of the third rails of water infrastructure, a process that conjures images of vital utilities closing and residents losing control over their water provider. However, one of the fundamental concerns across the country is that there are simply too many water systems, with too many unable to sustainably operate their systems and meet requisite water quality standards. A regional approach can reduce costs. As systems merge operations, the cost of water production can be reduced; one study found that a 100 percent increase in water production can lead to a 10 to 30 percent reduction in per-unit cost. In 2007, EPA produced a compendium of restructuring and regional options that are available in each state.

Localities have also benefited from forming public-private partnerships (P3s) with a private company to improve water services. The communities listed below pursued a P3 for their water systems in order to create efficiencies while ensuring regulatory compliance.

Examples of Public-Private Partnerships for Water Infrastructure

Share

Read Next

Examples of Public-Private Partnerships for Water Infrastructure

| Project | Type | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Clean Water Partnership, Prince George’s County, MD | Stormwater | Prince George’s County used a Design-Build-Operate-Maintain approach to tap into private sector expertise in meeting environmental standards and furthering local economic and community goals. The project invests in decentralized stormwater management installations covering 2,000 acres (with possible expansion). |

| Fairview Township, York County, PA | Wastewater | The small community of Fairview Township sold its wastewater treatment system to a private company. This sale ensured that urgent repair needs of the system serving 4,000 customers could be met without the municipality taking on additional debt. New projects taken on by the private water provider include the construction and installation of nearly 40,000 feet of new water and sewer mains, six new sewer pump stations, two new water pressure reducing stations, and 48 new fire hydrants. |

| Ransom Water System, IL | Drinking Water | The rural village of Ransom (population 371) is located in central Illinois, 70 miles west of Chicago. In 2015, the village’s drinking water showed dangerously high levels of radium, leading the village government to begin providing bottled water to residents. Lacking the resources to address the radium problem on its own, the village transferred its water system to a private company, Illinois American Water, in 2016 for $175,000. Illinois American Water invested approximately $2 million to install 10 miles of water main to connect the village’s customers to its existing water-distribution system that was already serving nearby areas. As a result, Ransom’s residents and businesses again had access to safe drinking water, in compliance with EPA requirements, and the village was able to cease distribution of bottled water. With the operational efficiencies in connecting to the larger system, customer bills declined by approximately 15 percent on average. |

| Tampa Desalination Plant, FL | Drinking Water | Using multiple service delivery methods, the Tampa Bay Region contracted with private partners for the construction of one of the nation’s largest seawater desalination plants. The primary purpose behind pursuing an alternative delivery approach was to develop new technology and transfer risk under complex circumstances. Tampa’s private partners are responsible for the operation, management, and maintenance of the new plant. |

Source: BPC, “Increasing Innovation in America’s Water Systems,” 2017; and BPC “Putting Capital to Work in Rural Infrastructure,” 2017.

Bundling and Leveraging

With thousands of water systems in the United States requiring upgrades and repairs, there is a distinct opportunity to accomplish multiple projects at the same time by bundling similar or nearby projects together. Bundling is a novel approach to project delivery gaining traction in the infrastructure sector, as seen in the Pennsylvania Rapid Bridge project and the Kentucky Wired broadband project. BPC’s recent report, Putting Private Capital to Work in Rural Infrastructure, lists five steps to creating a bundled project, from the initial enabling legislation that may be required to the final oversight.

The newly launched WIFIA program encourages systems to bundle multiple projects together within the same application. Of the 12 projects that received funding, one is $200 million for a bundled project in Baltimore that will repair, replace, and upgrade various parts of its wastewater, drinking water, and stormwater systems.

Another one of the 12 recently funded WIFIA projects is a $436 million award to the Indiana Finance Authority. With the new WIFIA loan, the Indiana Finance Authority will expand the reach of its Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (SRF) programs by 49 percent. The EPA encourages state SRF programs to maximize their potential capacity through innovative financing strategies, including using the SRF’s assets as collateral to issue revenue bonds. With the WIFIA loan, Indiana has essentially leveraged their original SRFs (which already includes an 80 percent contribution of federal funding) to further stretch their limited state resources.

Takeaway

Funding for water infrastructure has largely fallen on the shoulders of state and local governments. However, when water providers struggle to raise rates and proposals for maintenance projects fail to compete with other local priorities, the infrastructure can degrade to dangerous levels. In this absence of funding, local leaders have developed innovative approaches to stretch water dollars further. From innovative collaborations with public and private partners, to regionalization and bundling strategies, water providers have been able to make improvements to their infrastructure to provide safe and affordable water services.

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.