Retirement Tax Preferences: Cost Estimates Are Too High

As Congress pivots to tax reform, many lawmakers most importantly, the Republican chairmen of the relevant committees are looking to lower tax rates. To offset some or all of the resulting revenue loss, Congress is considering proposals to “broaden the base,” which means having more taxpayers actually pay those rates instead of receiving special tax preferences that lower their effective tax rate. Broadening the base requires curtailing tax expenditures provisions that provide tax benefits to specific groups of taxpayers and/or incentivize certain activities. These can take the form of deductions, credits, exclusions, deferrals, and preferential rates. Collectively, they cost the federal government around $1 trillion dollars a year in foregone tax revenues, and include many well-known provisions like the mortgage interest deduction and the earned income tax credit. (For a detailed primer, check out our previous blog.)

Given their price tag, the fact that some of these provisions are on the chopping block is unsurprising. Any serious tax reform effort would be incomplete if it failed to review these preferences and consider whether they are worthwhile and accomplishing their goals. These types of reviews are unfortunately rare the Government Accountability Office found in 2016 that federal agencies were failing to consistently review whether tax expenditures contributed to their goals or missions.

Lawmakers searching for revenue, however, should proceed with caution, as there is a false flag among this sea of costly expenditures a preference that appears to be far more expensive than it is: tax deferral for defined contribution (DC) retirement plans and Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs).

How Defined Contribution (DC) Plans Work and Why They Exist

Most DC retirement plans are “traditional” in structure, meaning that they are “tax deferred.” Tax deferral occurs when plan participants delay a portion of their income-tax liability. Contributions and any earnings that build up in DC accounts are not initially subject to income or investment taxes. Rather, income taxes apply to all assets at the time of withdrawal, which means that decades can pass before these accounts are taxed and the government collects its revenue. (A much smaller portion of retirement accounts are “Roth”-style, meaning that contributions are made with after-tax dollars and then withdrawals of principal and earnings are tax free.)

It is widely recognized that the United States faces a significant retirement security challenge. For most individuals, Social Security is only intended to provide a foundation of income in retirement, and even that base is currently unstable, with the program’s finances in a precarious state.

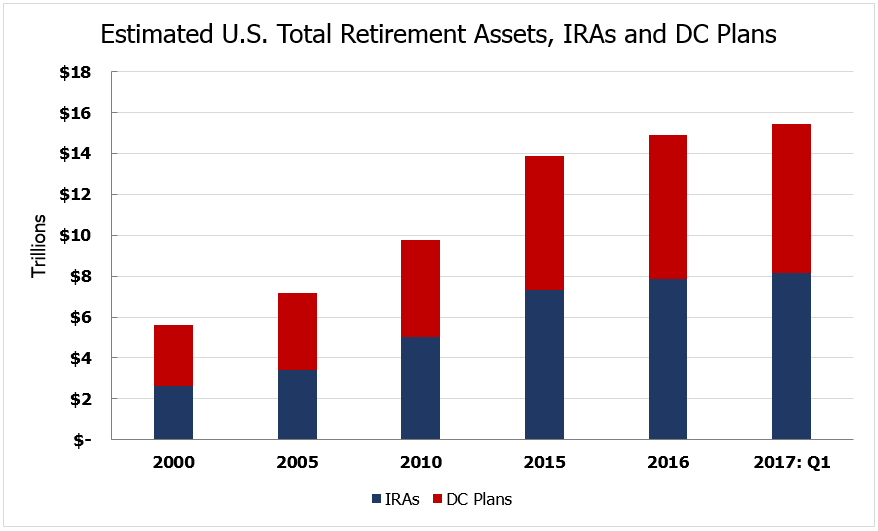

These preferences for retirement saving are in the tax code to encourage taxpayers to set aside a greater portion of their paychecks for retirement. Employers are also incentivized by the preferences to sponsor retirement plans and to provide a small part of their employees’ compensation in the form of account contributions. The result has been a large increase in the use of DC and IRA retirement plans over time, with more than $14 trillion held in DC and IRA retirement plans combined at the end of 2016 compared to under $6 trillion in 2000 (see figure below). While the efficacy and equity of these provisions are the subject of much debate, there is no disputing the fact that they currently represent a fundamental element of the U.S. retirement system.

Source: Investment Company Institute

Tax Deferral Is Different

The Treasury Department estimates that these tax preferences for DC plans and IRAs “cost” taxpayers around $79 billion last fiscal year (more if plans for self-employed individuals are included), and will “cost” approximately $1.194 trillion over ten years. But unlike estimates for other tax expenditures, these estimates are largely meaningless for policy purposes.

Here’s why: under federal budget rules, projections of costs are made on a cash-flow basis over the next ten years. This is a fair representation for most tax expenditures, which are deductions, exclusions, or credits going to individuals or companies that simply reduce the taxes paid in the year that they are claimed. In those instances, the normal budget scoring process fully captures the costs of lowered government revenue caused by the expenditures.

In contrast, this approach does not work for tax-deferred retirement accounts, where the government is foregoing revenue up front but collecting taxes on the resulting income and earnings in a later year. When an individual contributes to a traditional 401(k), those funds are unlikely to be withdrawn until sometime in retirement, which in most cases is more than ten years down the road. As budget projections fail to factor in revenue outside the ten-year window, tax-deferred accounts are actually far less costly to the federal government than they appear in the estimates.

The Bottom Line

Tax deferral for contributions to retirement accounts is similar to other tax expenditures in that they all reduce tax liability in the current year. But it is important to keep in mind that deferral is also very different from a tax deduction (such as for mortgage interest) or exclusion (such as for employer-sponsored health insurance). The way that tax deferral is currently accounted for by the federal government greatly overstates its costs.

In the push for tax reform, Congress will be pressured to search every nook and cranny for measures that broaden the tax base. Lawmakers should beware that the sticker price for tax deferral overstates its true costs.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.