Results and Implications of Turkey’s Local Elections

Jessica Atlas contributed to this post

Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) scored a better-than-expected result and substantial victory in the March 30 local elections. But the outcome of this contest, which selected municipal leaders, neither reveals the broad popular support that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdo?an claims to enjoy nor resolves the political tensions that have seized Turkey since last summer’s Gezi protests. Instead, the vote reveals an increasingly polarized country. With presidential and parliamentary elections looming, Erdo?an now faces a choice: pursuing a strategy of compromise or conflict. AKP government action on four critical issues?voting irregularities, social media bans, the pending intelligence law and relations with Israel?will give an early indication of which course he intends to follow.

Following the local elections, members of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s (BPC) Turkey Initiative hosted a panel to evaluate the results and their significance for Turkey’s domestic political struggles, foreign policy and relations with the United States. This discussion built on BPC’s paper, Turkey’s Local Elections: Actors, Factors, and Implications, released prior to the elections.

What the Elections Mean for AKP

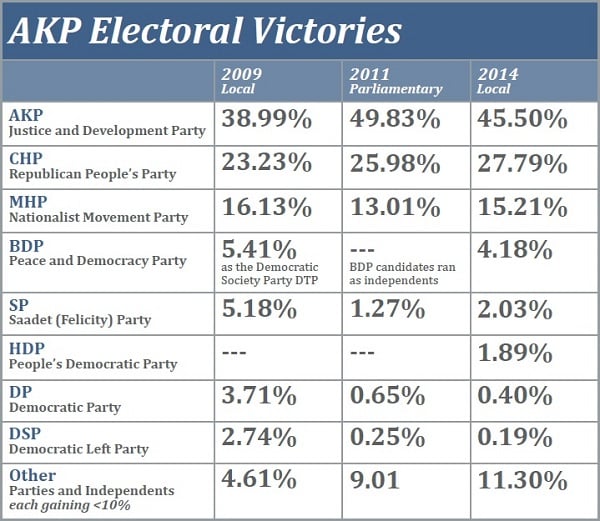

While not on the ballot himself, Prime Minister Erdo?an characterized the March 30 election as a referendum on his rule and his innocence in a number of corruption scandals that have plagued his government. There is no clear benchmark to gauge his party’s success. With 45.5 percent of the vote, AKP posted a significant increase, almost seven percent, over the last local elections in 2009. But there are good reasons why these two results might not be comparable. First, these local elections were dominated by national issues. Second, AKP has gained popularity since 2009.

Comparing recent Turkish election results

The 2011 parliamentary elections was a high water mark of AKP electoral success. The party secured 49.83 percent of the vote, a figure often referred to by AKP officials and rounded up to 50 percent to express the party’s popular mandate. A similarly high level of support for the AKP (53 percent) was found in polling conducted prior to the revelation of corruption charges against Prime Minister Erdo?an’s close associates on December 17, 2013, the subsequent leaking of recordings implicating him in the graft as well, and the March 14, 2014 death of a teenager injured during the Gezi protests. Compared to these benchmarks, then, the AKP’s popularity has waned, likely damaged by these successive blows. Nevertheless, the AKP was undeniably victorious in the local elections, leading some commentators to wonder why it has proven so hard for opposition parties to post better results. Noting that 75 percent of AKP voters said that the corruption allegations had “no effect” on their decision, columnist Murat Yelkin lamented that, “half of the corruption claims in any other democratic country would be enough to collapse the government; in Turkey it cost only a 5 point drop in support for Prime Minister Tayyip Erdo?an in the March 30 local elections.”

A detailed analysis of the results is certainly in order, particularly for the main opposition People’s Republican Party (CHP), which had hoped to win over 30 percent of the vote and secure the mayorships of Ankara and Istanbul, but succeeded in none of these goals. Understanding why voters stuck with the AKP is important to anyone seeking to challenge Erdo?an, but so is how other political dynamics played out among the electorate. Of particular interest should be whether and how the newfound political consciousness demonstrated by Turkey’s youth in Gezi Park translated into political mobilization, impacted turn out rates and affected voting behavior.

What the Election Results in Turkey Mean for U.S. Policy Makers

The key for U.S. policymakers, however, is the question of how Erdo?an himself interpreted the election result and how it will affect his future actions. With Turkey’s stability and role in the region at stake, the path Erdo?an follows should be of particular interest to U.S. policymakers. The hope that Turkey would serve as a model for Middle Eastern countries struggling to adopt democracy, present as recently as two years ago, has all but been forgotten. The challenge now is limiting AKP policies that add to the region’s tumult?such as helping Iran evade international sanctions or arming extremists in Syria,?or exacerbate divisions within Turkey.

One view, seemingly shared by economic analysts and international markets, is that the AKP’s victory will end Turkey’s political turmoil and pave the way back to political, and therefore economic, stability. On this interpretation, the electoral outcome has demonstrated to Erdo?an that his rule?whether he decides to run for president or remain prime minister?is secure, and his enemies have been unable to damage him. He will thus no longer need to use the polarizing and authoritarian measures that have roiled the country.

Another view, however, is that “there is no lesson that the AKP will draw from these elections and, unfortunately, Erdo?an will read the election results as a renewed mandate for his authoritarian governance.” With at least 45 percent of Turkey’s population unfazed by either allegations of corruption or Erdo?an’s majoritarian ruling style, even if he had the capability to, he appears to have little incentive to change his ways. If this reading is correct, the months ahead are likely to yield more of the repressive practices seen in the lead-up to the elections: lashing out at his enemies; stacking courts; banning social media; and manipulating the press.

The AKP’s actions in four areas will give an intimation of what to expect in the months ahead:

Electoral Irregularities

While Turkish elections have been previously considered free and fair, charges of fraud mar the March 30 results, with the opposition challenging the results in several cities. Amid other irregularities, blackouts interrupted the voting process throughout the country, completed ballots have been found in the trash of various polling places, the Interior Minister paid a late night “visit” to the election board as votes were being counted, different media outlets reported widely different vote tallies, and voters recounted being instructed to use pens with erasable ink. The most serious charges of irregularities have come in Ankara, where both AKP and CHP candidates declared victory and the CHP claim a significant discrepancy between the votes counted by the electoral board and votes counted by their monitors. However, the government does not seem to be addressing the legitimacy of the vote. Election Boards in Ankara and Antalya rejected the CHP’s appeals to recount votes, while an AKP request to recount votes in the northeastern city of A?r? was accepted. Taking accusations of vote tampering seriously and ensuring that they are resolved would strengthen citizens’ faith in Turkey’s democratic process?particularly important with two more elections coming up.

Social Media Bans

In response to a series of leaked recordings of conversations by Prime Minister Erdo?an, his family, and high-ranking government officials, Turkey blocked access to Twitter and then, subsequently, to YouTube. Widely decried both internationally and in Turkey, the government defended the ban, saying “Twitter has been used as a means to carry out systematic character assassinations by circulating illegally acquired recordings, fake and fabricated records of wiretapping.” The Twitter ban has since been lifted, following a court order, and legal proceedings are underway to challenge the blocking of YouTube as well. Erdo?an could demonstrate his commitment to democratic principles by voluntarily lifting the ban. As this seems unlikely?he declared of the court decision on Twitter, “we have to implement [the ruling], but we don’t have to respect it”?it is important that the government obey whatever verdict is rendered in the YouTube case.

M?T Law

In the last three months the AKP has introduced a number of bills to expand the government’s authority. Some have passed parliament and become law; one important one has not yet. It would expand the purview of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (M?T), exempt it from oversight, increase its immunities and ability to monitor Turkish citizens. Deputy AKP Parliamentary Group Chair Mustafa Elita? reported that “our first job after the elections will be the proposal that amends the M?T law.” If the parliament does indeed move ahead with the bill, which the opposition has warned would turn Turkey into a “mukhabarat” security state, it will be a good indication that Erdo?an has not relinquished his authoritarian tendencies.

Normalization with Israel

Prior to the elections, Turkish leadership took a more conciliatory turn in its rhetoric toward Israel and suggested that negotiations were on track to reach an agreement on compensation for the victims of the Mavi Marmara incident and normalize relations between the two countries. It is understandable that Erdo?an was not inclined to finalize the deal before the elections, it would have risked alienating his conservative and mostly anti-Israeli, if not anti-Semitic, base. Whether the deal proceeds now that the elections are over, and whether it is approved by the AKP-controlled parliament, will be an indicator of how sincere he is in fixing strained relations with the West. Should normalization of ties with Israel founder, it might be an indicator that Erdo?an was never serious about the deal and interested only in holding out hope of rapprochement to dissuade international leaders from criticizing his authoritarian domestic policies ahead of the elections.

To receive updates about BPC’s Turkey Initiative, subscribe for updates here.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now