Reforming an Antiquated Tax Code

This is the seventh and final post in our Budget Challenges Series, which explores the budget challenges facing the next president.

When discussing our nation’s fiscal challenges, the focus is often on spending. But this is only one side of the equation. An equally important consideration is whether revenues are raised through a well-designed tax code. Unfortunately, the current tax structure is antiquated and overly complex, due in part to high business tax rates that are internationally uncompetitive and overall revenue levels that are insufficient to cover necessary spending obligations. With such glaring problems, both parties agree that the antiquated tax code is a major budget challenge facing the next president and Congress.

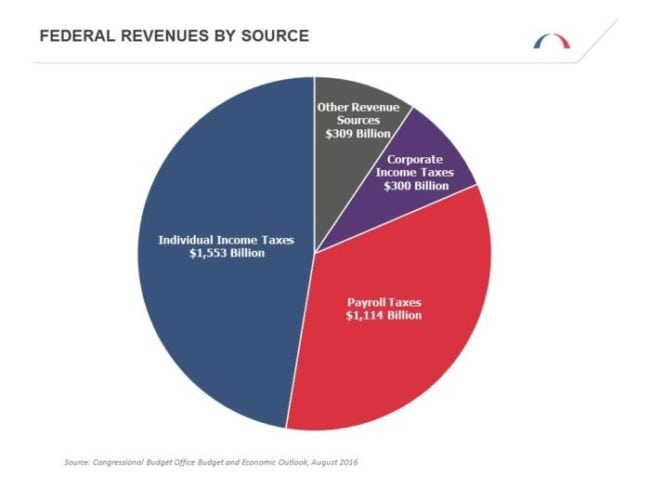

More than 90 percent of federal revenue currently comes from three sources:

- Individual income taxes, which are paid by individuals and businesses organized as pass-through entities (such as partnerships, S corporations, small businesses, and sole proprietorships);

- Corporate income taxes, which are paid on the profits of businesses organized as C corporations; and

- Payroll taxes, which are paid by wage-earners and their employers to fund specific programs, such as Social Security and Medicare.

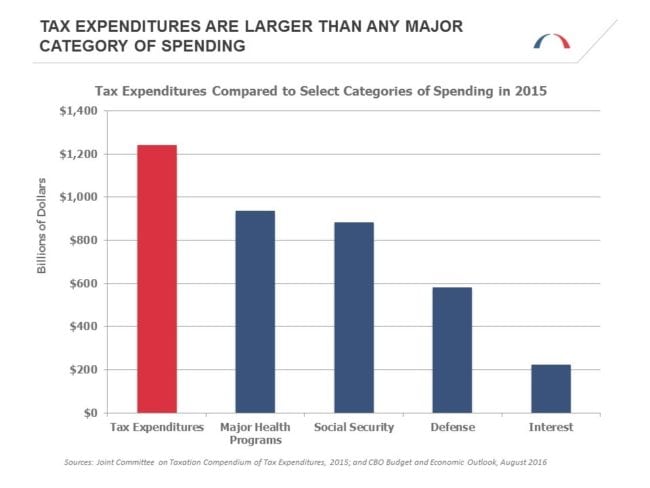

Within both the individual and corporate income tax, policymakers have created hundreds of exceptions known as “tax expenditures.” These are provisions that reduce the tax liability of taxpayers who meet certain criteria, such as having a mortgage or sponsoring health insurance plans. In 2015, total tax expenditures were valued at more than $1.2 trillion. That’s effectively $1.2 trillion of spending embedded in the tax code annually, dwarfing nearly every category of federal spending.

Having a large number of tax expenditures is a problem for three reasons. First, they can distort economic behavior by imposing differential tax burdens on equal-earning individuals. While some of these preferences may be justifiable, others are questionable and may produce unintended consequences. Second, tax expenditures cost the government revenues at a time of unsustainable deficits. Finally, they further hinder our tax system by necessitating higher tax rates to raise the same amount of revenue.

The last of these factors is particularly problematic in the corporate tax code. While businesses in some industries have tax burdens roughly equal to the statutory tax rate, others benefit substantially from tax expenditures and have a tax burden that is considerably lower. The result: despite the United States having one of the highest statutory corporate tax rates in the developed world (about 10 percentage points above the average country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), the effective rate, the average proportion of income that individuals and businesses across all industries pay in taxes, is actually slightly below the OECD average. This disparity between the statutory and effective rates in the United States produces the worst of both worlds: we are harmed internationally by a tax system that has comparatively high rates without benefiting from the revenue that a high-rate system with fewer holes might raise.

The United States is also at a competitive disadvantage because of how we tax the income of U.S.-based corporations that is earned abroad. Most countries in the OECD only tax profits earned within their borders (known as a “territorial system”). The United States, however, also taxes profits earned overseas by U.S.-based businesses when those profits are repatriated. This both discourages international firms from locating in the United States and incentivizes those that are based here to keep profits earned abroad outside the country rather than reinvesting them here at home.”

Many analysts agree that improving the tax code to make it more internationally competitive could increase economic growth (even though many determinants of economic growth, such as demographics, are simply outside the government’s control). Such a tax reform would make the United States more attractive to international investment and reduce compliance costs for businesses already located here. Higher taxable incomes that accompanied any economic growth resulting from tax reform would have the added benefit of producing additional revenue. That revenue could be used to invest in infrastructure, make business tax rates more globally competitive, and/or help address the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, stabilizing the national debt at its current share of the economy using only spending cuts would require at least an 8-percent reduction below current-law spending levels starting in 2017. Given the proven inability of policymakers to adhere to the budget caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and resistance to major entitlement reforms (especially ones that produce significant savings in the short-term), an immediate 8-percent cut from current-law levels (equal to $330 billion in the first year alone) is unrealistic.

Any realistic deficit-reduction plan will likely require some combination of tax increases and spending cuts.

Unsurprisingly, nearly every bipartisan deficit reduction plan, including the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Debt Reduction Task Force (also known as Domenici-Rivlin) and President Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (a.k.a. Bowles-Simpson), has recommended reforming the tax code by reducing both tax rates and tax expenditures in a way that, on net, increased revenues for the federal government and promoted economic growth.

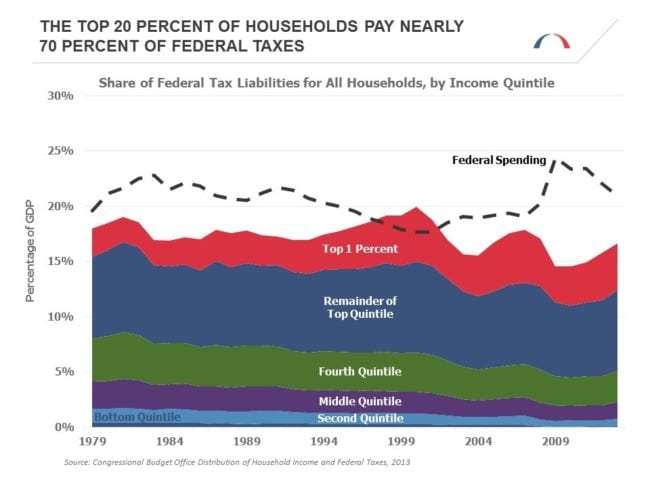

That being said, stabilizing the national debt through revenue increases alone is also farfetched, as all taxes would need to be 9 percent higher each year beginning in 2017 in order to do so. Further, if such tax increases were concentrated only among the “top 1 percent” of Americans with the highest incomes, as is a popular proposal on the left, stabilizing the debt would require a nearly one-third increase in their tax burden. Thus, any realistic deficit-reduction plan will likely require some combination of tax increases and spending cuts.

Whether economic growth, simplification, or deficit reduction is the primary objective of reforming the tax code, tax reform remains fundamentally necessary today. Since the last major tax reform in 1986, the number of tax expenditures has nearly doubled. And just last year, Congress voted to expand or make permanent tax expenditures that will cost $800 billion over 10 years without offsetting the cost.

Rather than continuing to increase the deficit and further complicate the tax code, the next president and Congress should address these challenges in the context of a bipartisan tax reform that will boost incomes and create jobs. Whether policymakers choose to do so in stages, perhaps by doing personal and corporate income taxes separately, and payroll-tax changes as part of reforms to make the programs that they fund sustainably solvent, or in one big comprehensive tax-reform package, it would almost certainly help solve a major budget challenge that needs to be addressed.

Want to try your hand at crafting your own budget? Check out the Federal Balancing Act Interactive Budget Simulator developed by the Bipartisan Policy Center and Engaged Public.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.