Prioritizing Nutrition in the Farm Bill Conference Process

Despite the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) success in reducing hunger, to date, it has been less successful in promoting nutrition. While the program has historically focused on increasing caloric intake, the problem now is being unable to afford, access, and prepare healthy foods.

Congress has now finalized the list of members of the farm bill conference committee that will work over the coming weeks to reconcile the House and Senate versions of the bill. Food assistance policy is an area ripe for innovation to address the obesity crisis if policy makers made it a priority.

The Food Insecurity and Nutrition Incentive Program (FINI) and the SNAP-Education program are the two main ways that Congress and USDA currently work to improve nutrition among SNAP participants. Both would be significantly altered by one or both proposed bills (Figure 1).

Figure 1

.

Overview of FINI and SNAP-Ed in the 2018 Farm Bill

Share

Read Next

Funding Levels

Program | 2017 | 2018 |

| Public Housing Capital Fund | $1.941 billion | $2.75 billion |

| HOME Investment Partnerships Program | $950 million | $1.362 billion |

| Housing Trust Fund | $219 million | $266 million |

| LIHTC | $9 billion | $10 billion |

| Choice Neighborhoods | $138 million | $150 million |

| CDBG | $3.06 billion | $3.365 billion |

| Rural Housing Service | $30.15 billion | $30.38 billion |

| Native American Housing Block Grant | $654 million | $755 million |

FINI in the 2018 Farm Bill

In 2008, Congress responded to the obesity epidemic by funding the Health Incentives Pilot, which later became FINI in 2014. FINI provides grants to states, municipalities, community organizations, etc. to incentivize the purchase of fruits and vegetables by SNAP participants.

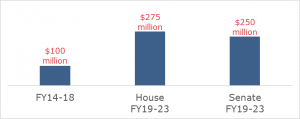

Both bills propose to more than double funding for the program to levels that would allow it to be captured in CBO’s baseline projection for the 2023 farm bill, which is a major win for the sustainability of the program. The House bill authorizes $275 million over five years while the Senate bill authorizes $250 over five years?both substantial increases over current levels (Figure 2). Both bills also create technical assistance infrastructure for FINI with the house bill proposing a single Training, Evaluation, and Information Center for FINI and the Senate bill authorizing one or more Center(s) on Training and Technical Assistance and Center(s) on Information and Evaluation.

Figure 2

.

Proposed Changes in FINI Funding

SNAP-Education in the 2018 Farm Bill

Since its reformation in 2010, SNAP-Ed has supported evidence-based nutrition-education and obesity-prevention strategies. Even though it is the largest nutrition education program under the USDA, its current funding only reaches a small percentage of SNAP families.

In its proposed bill, the Senate does not change the structure or funding of SNAP-Ed but instructs states to use an electronic reporting system and submit annual evaluation reports.

The House farm bill combines the Expanded Food & Nutrition Ed Program (EFNEP) with SNAP-Ed. Specifically, the proposal would move SNAP-Ed administration within USDA from FNS to the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA, which houses EFNEP) and would move administration at the state level from state SNAP agencies to Land-Grant Universities (LGUs, which administer EFNEP).

At both the federal and state level, this would mean moving SNAP-Ed away from the agencies that administer SNAP. The state-level change, in particular, would upend the program’s work. State agencies currently sub-grant to other state and local entities and those partnerships and contracts would all be severed if state agencies lost SNAP-Ed funding. While LGUs receive a substantial portion of SNAP-Ed funds and are valuable implementers in many states, the evidence is, at best, unclear as to whether the program would improve under their management, but the disruption of services provided by other implementing agencies would be unavoidable.

Under the house proposal, this new combined SNAP-Ed program would receive a mandatory $485 million for fiscal 2019?roughly $11 million less than the combined amounts that SNAP-Ed and EFNEP would have received if not combined?plus up to an additional $65 million in discretionary funds. The bill would also immediately change (with no phase-in period) the program’s funding formula to be based purely on states’ SNAP participation rates. For most of its history, SNAP-Ed was a 1-to-1 matching program wherein USDA reimbursed 50 percent of state SNAP-Ed expenditures. This formula was altered in 2010 and the current funding formula?which just finished a slow phase-in in fiscal year 2018?is based half on current participation rates and half on historical SNAP-Ed receipts from when funding was provided to states on a matching basis.

Missed Opportunities

Earlier this year, BPC convened the SNAP Task Force which recommended ways that health and nutrition could be prioritized within SNAP and other federal programs. The overarching theme of the Task Force’s recommendations for SNAP was that improving diet quality should be a core objective of this nutrition assistance program alongside efforts to reduce food insecurity and maximizing program. No efforts were made in this either chamber’s farm bill to move USDA in this direction.

Programs such as FINI have increased fruit and vegetable purchases, but have had no effect on participants eating unhealthy foods. Emerging research concludes that the most effective strategy (to both reduce cost and improve health) is to combine incentives for healthy foods with disincentives for foods that contribute to chronic disease and obesity. To achieve these synergistic benefits, the SNAP Task Force recommended eliminating sugar-sweetened beverages from the list of items that can be purchased with SNAP benefits.

Additionally, despite establishing technical assistance centers for FINI, neither House nor Senate bill did the same for SNAP-Ed despite the program being an order of magnitude larger than FINI. In the past, the USDA established the Regional Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention Centers of Excellence to support SNAP-Ed, however, these centers only existed briefly and are no longer funded. Senator Tom Carper (D-DE) offered an amendment to create an Office of Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention Training and Technical Assistance, but it was not included in the final version of the bill.

Other missed opportunities include expanding the USDA’s ability to conduct pilot programs related to nutrition promotion research (strategies to “nudge” shoppers toward healthier options), as well as strengthening SNAP retailer standards to improve the food environment for all shoppers. Giving the USDA increased ability to collect and share store-level data on all products purchased with SNAP funds is an additional step that could be taken towards creating a healthier environment for all shoppers. While the House authorized periodic collection of a sample of this data, the limited nature of the data collection and the inability to share store-level data with state SNAP agencies will limit its utility.

Going Forward

The conference committee will attempt to stitch together the two bills in the coming weeks, and key differences such as SNAP work requirements and changes to conservation programs will likely steal much of the news coverage. Despite the relative lack of focus on nutrition in the 2018 farm bill process thus far, the conference committee has the power to resurface amendments or ideas that didn’t make it into either bill. Whether they choose to do that or not, the obesity epidemic is projected to worsen and the economic impacts will steadily become harder for policymakers to continue to ignore.

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.