How the Sequester Works if the Joint Select Committee Fails

UPDATE: The Sequester: What You Need to Know, February 22, 2013

The third in a series of posts on the Budget Control Act.

Now that the Budget Control Act (BCA) has been signed into law, the focus shifts to the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (JSC) tasked with finding $1.5 trillion in spending cuts and/or revenue increases over the next ten years (These savings would come on top of the roughly $900 billion saved up-front from capping discretionary spending; for details, see our earlier post). But what happens if they fail to come to an agreement? That’s what the “sequester” is for. It will act as a “sword of Damocles” hanging over the JSC in the hopes of forcing action.

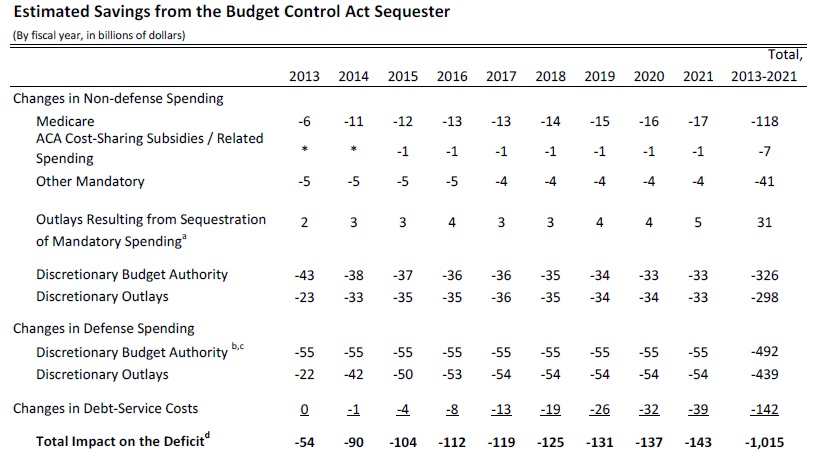

Each party would face cuts to spending categories that it generally tries to protect ? the hope being that both parties will have sufficient incentive to move towards the middle and strike a deal. Motivating Democrats are potential cuts to domestic discretionary programs, the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) cost-sharing (exchange) subsidies, Medicare, and a couple other mandatory spending programs. On the Republican side, defense spending would be cut by a hefty 10 percent. If the JSC cannot agree to at least $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction (or the package fails to be enacted into law), these automatic sequester cuts would take effect to roughly bring the budget savings up to $1.2 trillion through 2021.

UPDATE: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Sequester, May 18, 2012

The sequester would be implemented beginning in 2013 as an across-the-board cut to all non-exempt budget accounts. (The cut to most of the Medicare program is capped at 2 percent.) Like most previous sequesters, however, this one is riddled with exemptions. Social Security, veterans’ benefits, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), unemployment insurance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), food stamps (SNAP), and a host of other programs (mostly those benefitting individuals with low incomes) are all exempt from sequester ? see the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010, starting on page 22, for a list of most of the exempt programs. Revenues, which many Democrats were arguing to be included in the sequester, are also exempted. But, as detailed above, important priorities of both parties are still laid on the chopping block.

New Report

Indefensible: The Sequester’s Mechanics and Adverse Effects on National and Economic Security

A joint report from BPC’s Task Force on Defense Budget and Strategy, a joint effort of the Economic Policy Project and the Foreign Policy Project

June 2012

Now for the fun details ? if numbers aren’t your thing, you should probably stop reading:

1. If the JCS fails to report or its recommendations are not enacted, then the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is required to cut (by means of a sequester) $1.2 trillion from the budget during the years 2013-2021.

2. To account for the fact that part of this $1.2 trillion will come in the form of interest savings, the BCA instructs the OMB to reduce the size of the sequester by 18 percent, to $984 billion.

3. The dollar amount of the cuts must be evenly divided in each of the nine years, meaning an annual cut from the baseline of $109 billion.

4. The cut is split evenly between the non-exempt portions of defense (function 050) and non-defense spending, requiring approximately a $55 billion annual cut to each. Aside from exempt programs (of which there are many ? see above), these cuts are spread among both mandatory and discretionary spending.

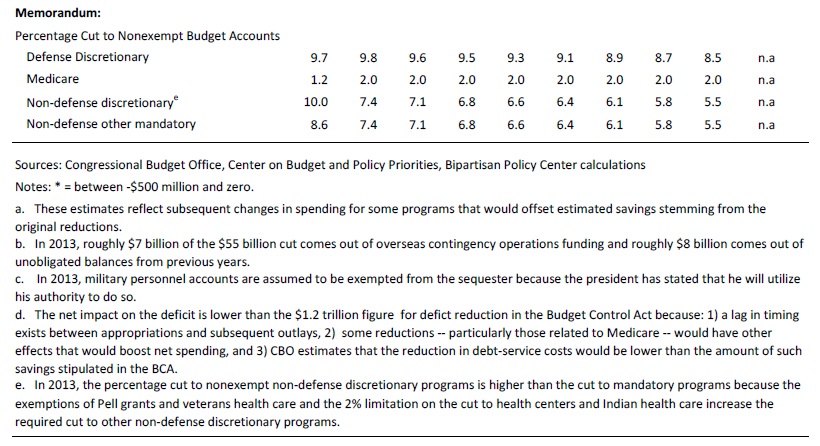

- For example, in FY2015 (mainly selected to illustrate the first full fiscal year for which the ACA’s exchanges will be up and running), the uniform percentage reduction required for non-exempt, non-Medicare programs would be approximately 7 percent (on top of the cuts that the discretionary accounts took from the BCA caps). This sequester would translate to a $37 billion cut to non-defense discretionary budget authority, a $1 billion cut to the ACA cost-sharing exchange subsidies, and a $5 billion cut spread across the remaining non-exempt mandatory spending programs (farm subsidies and several other miscellaneous ones). The 2 percent Medicare cut in that year would be about $12 billion (note: some Medicare payments are exempt from the sequester, such as Part D subsidies for low-income beneficiaries and for catastrophic coverage, so the 2 percent cut only applies to roughly $600 billion of the program in FY2015).

- For defense, almost the entire $55 billion is cut from discretionary budget authority (since non-exempt mandatory spending on defense is less than $2 billion). In 2013, this amounts to approximately a 10 percent cut (on top of the cuts that are made initially through the discretionary caps in the BCA). In 2021, since the defense discretionary baseline grows, but the required dollar cut does not, the $55 billion amounts to an 8.5 percent cut.

- For non-defense spending, the analysis is a bit more complicated. All of the non-exempt budget accounts will be cut by a uniform percentage necessary to achieve the $55 billion annual cut, except that the reduction to most of the Medicare program is capped at 2 percent (as it was under Gramm-Rudman-Hollings in the 1980s). Therefore, if the percentage reduction to Medicare would have exceeded 2 percent (which it certainly would if the sequester has to comprise the entire $1.2 trillion), then the uniform percentage cut to all other non-exempt programs is increased to a level sufficient to achieve the $55 billion annual cut.

The breakdown of the cuts from the sequester is spelled out in more detail in the chart below (which also lays out the up-front savings achieved by the discretionary caps in the BCA). Please note, however, that with respect to discretionary spending, the sequester cuts budget authority (BA), not outlays. Therefore, the actual deficit reduction from the sequester is a bit lower than $109 billion in the first few years.

UPDATE: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Sequester, May 18, 2012

To view and share a larger version of the chart above, click here.

Bill Hoagland (former staff director of the Senate Budget Committee under Chairman Pete Domenici and policy advisor on budget and financial matters to Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist) and Barry Anderson (former deputy director and then acting director of the Congressional Budget Office) were consulted.

UPDATE: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Sequester, May 18, 2012

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now