How many unaccompanied children show up for immigration court?

Key Takeaways:

- In FY 2014, immigration courts received nearly 61,000 cases that concerned unaccompanied children. Of these cases, 71 percent are still pending.

- Among FY 2014 cases that have been decided so far, 53 percent were decided in absentia, meaning that the child did not attend the hearing.

- Because most recent cases are still pending, it is too early to determine how many will ultimately appear for their court date. In prior years, unaccompanied children attended their hearing in 60 to 80 percent of cases.

After last summer’s surge of Central American child migrants, many were processed and issued notices to appear in immigration court to determine whether they should be sent home. Some argue that these migrants need to be detained while awaiting their court cases, both to ensure they appear for their hearings and to deter others from coming. Others contend that detention is not necessary or that attendance in court can be ensured by less restrictive alternatives to detention.

This debate has made the frequency with which migrants appear in immigration court an important point of interest for policymakers and the public. In particular, many stakeholders want to know how many of last summer’s child migrants are showing up for court. When an immigrant does not appear for their scheduled court hearing, the case may be decided “in absentia,” which means the immigration judge can enter an order in the absence of the defendant. The percentage of cases decided in absentia is the best available measure of migrants’ court attendance. In more than 99 percent of child cases decided in absentia since FY 2005, the immigrant was ordered removed.

Because current law allows many Mexican migrants to be returned expeditiously without a court date, the large majority of these court cases concern Central Americans. Nearly 93 percent of child court cases that began in fiscal year (FY) 2014 concern children from either El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras (the Northern Triangle), compared with 4 percent from Mexico. Since FY 2005, 85 percent of cases have been from the Northern Triangle, compared with 9 percent from Mexico.

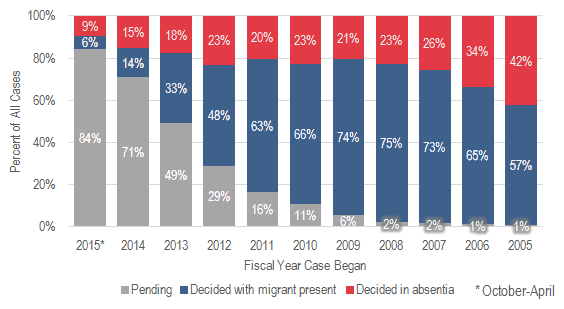

Most recent cases are still pending

Of the nearly 61,000 unaccompanied child cases that began in FY 2014, more than 43,000 (71 percent) were still pending at the end of April 2015. The high proportion of pending cases is due in part to a large and growing backlog in the immigration court system. As Figure 1 shows, substantial backlogs exist for each of the past few years?for example, nearly one-third of the cases that began in FY 2012, and one-sixth of the cases that began in FY 2011, have yet to be resolved. Although the Obama administration has taken steps to process children more quickly than other migrants, these figures suggest that it could take a few years to work all of the recent cases through the system.

Figure 1. Status of child migrant cases by year case began

Source: TRAC. For underlying data, see supplemental table attached below.

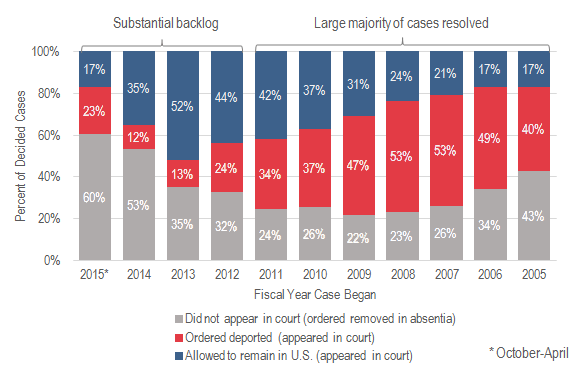

Among cases that have been decided so far, most have been decided in absentia

As of April 2015, nearly 18,000 (29 percent) of the cases that began in FY 2014 had already been decided. Of these, 53 percent were decided in absentia, and 47 percent were decided in the presence of the migrant (Figure 2). This means that in the majority of cases that have been decided so far, the child did not attend their hearing.

Some stakeholders have divided the number of absentia rulings by the total number of cases filed and argued that more than 80 percent of children have attended their court date. This deduction is erroneous because it counts pending cases as though the migrant attended their court date. Although it is possible that child migrants will have perfect attendance in pending cases, it is more reasonable to assume that some pending cases will eventually be decided in absentia.

We don’t know how many pending cases will be decided in absentia

Because less than one-third of the cases that began in FY 2014 have actually been decided, it is unclear how many will ultimately fail to appear in court. Cases that are resolved quickly are unlikely to be representative of cases that take longer. In almost any situation where the migrant does not attend their court date, the case can immediately be decided in absentia. By comparison, if the migrant attends, the case may or may not be decided immediately?in some cases, a follow-up hearing must be scheduled. As a result, the number of pending cases includes an unknown number of cases in which the child attended the initial court date but had a follow-up hearing scheduled. Thus, while it is correct to say the child did not attend their hearing for the majority of cases that have been decided, it is unclear how many additional children attended their hearing but did not have their case resolved.

Historical data suggest that 60 to 80 percent might ultimately attend their court date

In light of the uncertainty surrounding pending cases, it may be more informative to examine cases that began a few years back. Among unaccompanied children whose cases began between 2007 and 2011, 76 percent of resolved cases were decided with the migrant in attendance. By contrast, in 2005 and 2006?around the time of the last surge in Central American migration?61 percent of child cases were decided with the child in court. If history is a reliable indicator, the percentage of children from the latest wave who attend court may fall in this general range of 60 to 80 percent.

Figure 2. Outcome of resolved child migrant cases

Source: TRAC. For underlying data, see supplemental table attached below.

More detailed data could enable stakeholders to draw more certain conclusions about recent cases. Namely, if data described the percentage of pending cases that already had an initial court date, it might be easier to speculate about how many cases might ultimately be decided in absentia. However, this would still require the observer to make assumptions about the migrant’s future behavior?for example, some portion of migrants who attend their initial hearing may not attend the next one.

Previously, we have written that backlogs in the immigration court system are harmful to the enforcement system and to the immigrants. The unsatisfying answer to today’s simple question illustrates that the backlog can also make it harder to answer questions that would be informative to policymakers and the public. Until more cases work their way through the court system, historical data will provide the best look at how many children show up for their date in immigration court.

View all data on immigration court outcomes for unaccompanied children

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.