New Turkey or New Government? The June 2015 Parliamentary Election

.png) In August 2014, upon his ascension from prime minister to Turkey’s first directly-elected president, Recep Tayyip Erdo?an heralded the creation of a “New Turkey.” Whether Erdo?an and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) can achieve that ambition or whether there will be a shift in power in Turkey?to an AKP-led coalition government or potentially even a government without the AKP?will be determined on June 7, 2015, when Turks go to the polls to elect a new parliament. The outcome of the voting will likely be decided by two dynamics: the performance of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP); and the freedom of the election. In turn, two additional factors will play a major role in determining what the impact final vote tally is on Turkey’s trajectory: the HDP’s political strategy; and the relationship of Erdo?an to his prime minister, Ahmet Davuto?lu. Regardless of the outcome, polarization and social tensions in Turkey are almost certain to rise?and potentially boil over?while, at least in the short-term, the troubled U.S.-Turkey relationship is unlikely to improve.

In August 2014, upon his ascension from prime minister to Turkey’s first directly-elected president, Recep Tayyip Erdo?an heralded the creation of a “New Turkey.” Whether Erdo?an and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) can achieve that ambition or whether there will be a shift in power in Turkey?to an AKP-led coalition government or potentially even a government without the AKP?will be determined on June 7, 2015, when Turks go to the polls to elect a new parliament. The outcome of the voting will likely be decided by two dynamics: the performance of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP); and the freedom of the election. In turn, two additional factors will play a major role in determining what the impact final vote tally is on Turkey’s trajectory: the HDP’s political strategy; and the relationship of Erdo?an to his prime minister, Ahmet Davuto?lu. Regardless of the outcome, polarization and social tensions in Turkey are almost certain to rise?and potentially boil over?while, at least in the short-term, the troubled U.S.-Turkey relationship is unlikely to improve.

What’s At Stake?

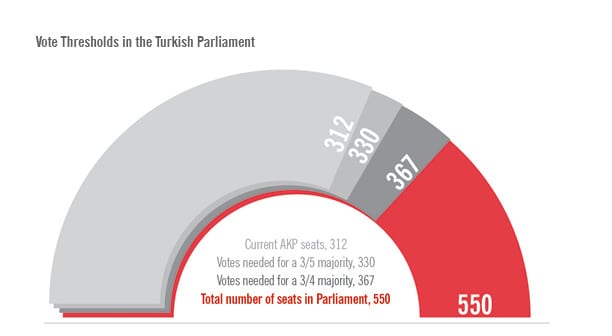

Central to Erdo?an’s vision of a New Turkey is also a new political system, featuring a strong executive presidency. The AKP currently holds 312 seats in Turkey’s 550 member parliament, after attaining 49.83 percent of the vote in the 2011 parliamentary elections. To pass the kind of sweeping constitutional changes that Erdo?an wants, the AKP would have to increase its majority: 330 seats (a three-fifths majority) would allow the AKP to put proposed constitutional changes to a public referendum; and with 367 seats it could pass constitutional amendments outright, without a public referendum. The 2015 parliamentary election could, therefore, bring a New Turkey or a new government.

HDP and The Electoral Threshold

The most important factor in determining this election’s outcome, and the fate of Erdo?an’s aspirations, will be the HDP’s showing at the polls. In the past, Kurdish candidates have opted to run as independents, exempting them from Turkey’s 10 percent electoral threshold. Now, running as a party, the HDP must gain at least 10 percent of the total vote to enter parliament. If they fall short, they will not be represented at all.

A Free and Fair Election?

There is also a very real fear of fraud in this election. Only a few votes will determine whether the HDP surpasses the 10 percent threshold, creating incentive for vote tampering. Such concerns are not unjustified; the local elections of March 2014 were marred by an unprecedented number of accusations of irregularities and vote-rigging in the AKP’s favor. While it remains to be seen whether the ballot-casting itself will be free, the fairness of Turkey’s upcoming parliamentary election is already a foregone conclusion; the playing field is hardly level. Indeed, opposition parties have complained to the board overseeing the elections about extensive and disproportionate media coverage of Erdo?an and Davuto?lu at official events that are essentially thinly-veiled AKP propaganda, but their appeals have been rejected, casting doubts on the board’s willingness to safeguard the fairness of the vote.

Erdo?an and Davuto?lu: Together Forever?

The election result, no matter what it is, will be a test of the Erdo?an-Davuto?lu partnership. Though technically holding the

more powerful office, Davuto?lu is obviously the junior partner in this relationship. Equally clear is that he has the self-esteem and ambition to seek a more prominent role in leading the country. What remains uncertain is whether he might act on that aspiration. In the case of a resounding AKP victory, Davuto?lu might be content to remain in Erdo?an’s shadow, gambling that he might one day inherit the presidential mantle. Or, he might see an electoral win as a chance to assert his credentials as party leader and prime minister, prompting a struggle between Turkey’s two most powerful politicians. If the AKP doesn’t perform well, on the other hand, Davuto?lu might embrace a coalition government as a means for circumscribing Erdo?an’s authority and promoting himself as a unifying leader. More likely, however, is that a loss will be blamed on Davuto?lu and lead to his ouster.

Implications

After over a decade of AKP rule, Turkish society is profoundly divided. Furthermore, political fault lines have only deepened since the mass protests of summer 2013?much of it as a result of President Erdo?an’s polarizing rhetoric. The widespread concerns of electoral fraud in the lead-up to the elections reveal a deep lack of trust in Turkey’s political system and, no matter the outcome on June 7, the parliamentary elections seem likely to further deepen that polarization instead of fostering cohesion.

Escalation of political violence is a real possibility. Continued AKP rule could rile leftist extremists. On March 31, 2015, members of the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party-Front executed a state prosecutor in a major propaganda feat. Pre-election violence, particularly against the HDP, has been more severe in the months ahead of the June vote than in years past. According to the Turkish Human Rights Association, out of 126 instances of violence, 114 were against the HDP, including two bomb attacks against HDP local headquarters in Adana and Mersin.

Meanwhile, the PKK could resume large-scale attacks if the HDP fails to enter parliament on June 7 or if Erdo?an backtracks on his promises to resolve the Kurdish question. If the AKP government is suspected of engaging in electoral fraud, especially if the electoral board refuses to acknowledge it, widespread demonstrations, beyond just Turkey’s southeast, are likely.

But a weakened or chastised AKP is unlikely to lead to a more stable outcome, at least in the short-term. Historically, coalition governments in Turkey have been fractious and unstable. With a weakening economy, political bickering would not serve Turkey well. There is also reason to fear that the foreign and home-grown Islamic extremists who use Turkey as a jihadist highway to the conflicts in Syria and Iraq might capitalize on any uncertainty.

Only a few years ago, observers had hoped that Turkey would show the world how a secular, free-market democracy could exist in a Muslim-majority country. It would be one of history’s greatest ironies should President Erdo?an manage to refashion his country in a way comparable to its more authoritarian neighbors. But even if Erdo?an fails to have his way, Turkey is just as likely to suffer.

Share

Read Next

Downloads and Resources

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now