Turkey Election Raises More Questions Than It Answers

Over the last two years Recep Tayyip Erdo?an, now Turkey’s president, and his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) have strengthened their grasp on power at the expense of social cohesion. Casting their ballots in the general election on June 7, Turkish voters upended this dynamic: venting their frustrations by denying AKP a parliamentary majority. A significant demonstration of Turks’ aversion to Erdo?an’s burgeoning authoritarianism, this vote has alleviated concerns about possible social unrest. At the same time, however, it has also ushered in political uncertainty that is quite likely to lead to yet another election. With the elections failing to deliver a definitive and sustainable political outcome, the next several months will be determined by how both Turkey’s parties and society react to this prolonged campaign: will uncertainty turn into instability or will it be used as an opportunity to put the Turkish polity on surer footing?

The Result: Winners and Losers

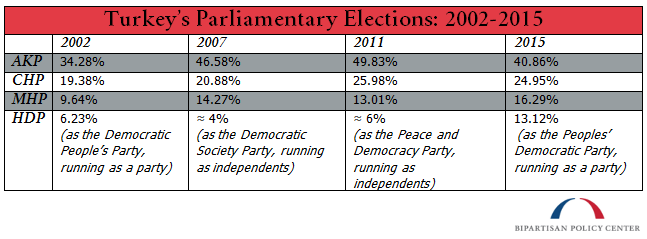

Counterintuitively, the apparent winner of this election is its last place finisher: the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Its liberal message of inclusion and multicultural rights won it about 13 percent of the total vote and about 78 seats in parliament. The major question of this election was whether the HDP would be able to cross the 10 percent threshold for parliamentary representation. With polls showing its support fluctuating right around the 10 percent level, its success was less than certain, even at the last minute. Yet, the party and its co-chairman, Selahattin Demirta?, far exceeded expectations and turned what had been a regional, ethnic party into a national political player.

Although it grew out of the Kurdish political movement, HDP’s win could not have been accomplished without broader national support. HDP candidates, running as independents, garnered only approximately 6 percent of the vote in the 2011 election. It is likely that the HDP was able to add another 3 percentage points to its total by courting conservative Kurds who had previously supported AKP, but this still would not have put it over the top. The votes that catapulted HDP to 13 percent?adding about 3 to 4 points to its total?likely came from Turks in the west of the country. Some of these were liberal democrats who bought into Demirta?’ vision of individual rights and democratization. However, the majority of this group were likely tactical voters who might otherwise have supported the main opposition, social democratic Republican People’s Party (CHP), but calculated that the best chance of ousting AKP from the majority would come from bringing HDP into parliament.

Many of these voters?likely Kemalists who might have been suspicious of Kurdish attempts to alter Turkish political identity or sovereignty?were likely persuaded at the last minute to support HDP. Demirta? responded to a bombing at an HDP election rally in Diyarbakir on June 5, which killed two and injured scores, with pleas for calm rather than incitement to revenge. This reassured voters who might have been on the fence that Demirta? was a responsible, national politician and not a separatist leader, sending enough of them to the polls in favor of HDP to grant it a major upset.

The nationalist National Movement Party (MHP) also delivered a strong performance, adding four points to its 2011 vote tally with a final result of 16.3 percent, good enough for around 81 seats. This increase was likely a result of conservative nationalists abandoning the AKP camp as a result of dissatisfaction with the party’s support for a peace process with the Kurds, power grab, and weakening economic performance.

CHP, on the other hand, did not do as well at the polls as it had hoped, despite a positive and issue-oriented campaign. Party leader Kemal K?l?çdaro?lu had hoped to improve CHP’s performance from 26 percent in 2011 to above 28 percent this time around, promising to resign should he fail to attain that goal. He was not able to deliver: CHP lost a point, falling to 25 percent. Still, K?l?çdaro?lu has declared this a victory for the party and does not seem keen to depart. “We have ended an oppressive era through democratic ways. Democracy has won; Turkey has won,” he said in a short speech after the election. “This result does not require my resignation.” Perhaps he looks to the handful of seats that CHP picked up, going from 130 parliamentarians to about 135, due to Turkey’s complicated electoral system. Or perhaps he calculates that CHP would have hit his target, if only tactical voters had not abandoned the party in favor of HDP.

The clear loser of the election, however, was AKP. Not only will it be unable to pursue constitutional changes to remake Turkey’s political system as it had hoped, which would have required controlling at least 330 votes in the 550 seat parliament, it did not even manage to eke out a simple majority of 276 seats. Instead, with about 40.9 percent of the vote, AKP will be apportioned less than 260 seats. This is a significant loss compared to the 49.8 percent and 312 seats it garnered in 2011. The major question for the party, should it engage in such self-reflection, will be who is responsible for this loss: Erdo?an or his self-selected replacement as party leader and prime minister, Ahmet Davuto?lu.

Still, when AKP first entered government, winning a majority of seats in the 2002 election, it only secured less than 35 percent of the vote. Whatever difficulties the party is facing, it continues to command a more sizable base than any other party and to attract voters from beyond its core constituency. Though chastised, AKP remains a potent political force in Turkey.

Finally, June 7 was also a major victory for Turkey’s civil society. Fearing electoral fraud?allegations of which marred the March 2014 local elections?nongovernmental groups had been formed and joined together to train and dispatch election monitors to voting places. While media intimidation and other violations might have tarnished the fairness of this election, Turks rallied together to ensure its freedom.

What Comes Next?

With no one party able to rule with a majority, there are three main scenarios for how a government might now be formed. None appears to be particularly tenable or stable:

- AKP forms a coalition government with either:

- MHP

- HDP

- CHP

- The three opposition parties?CHP, HDP, and MHP?band together to form a coalition.

- AKP attempts to rule from the minority, looking for support from other parties to support its agenda.

The first scenario might appear unlikely since already the AKP has ruled out seeking a coalition and the three other parties have pledged not to join a government with AKP, even if it offered. Yet, it is all but certain that negotiations have already begun behind the scenes; each party has strong incentives to gain power, even if it is shared with AKP. HDP needs to be in government to deliver on its promise of greater rights for Turkish minorities. The only way for MHP to stop the ongoing peace process with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), which it staunchly opposes, is to trade its votes for a change in AKP policy. And CHP, having wandered the political wilderness since 1996, might calculate that it can only regain its former strength by accessing the patronage networks that come with ascending to power.

Since all three want power but have run against AKP, a three-way coalition might seem compelling. Yet, it is unlikely that these parties will be able to work out their differences to pursue a joint government. Even though some experts have suggested a limited coalition with the sole purpose of purging AKP corruption from government and creating a more fair electoral system, the gulf between the opposition parties, especially between HDP and MHP, continues to appear unbridgeable. Whatever distaste all three may share for AKP, this election result has probably removed whatever shared motivation for reform they might have had: AKP no longer seems invincible and the electoral system is no longer a barrier.

Nor does AKP necessarily have incentive to seek a partner. First of all, the party is quite likely to be more consumed with internal recriminations and power struggles in coming days?with Davuto?lu fighting to survive as party leader against Erdo?an’s likely attempt to oust him?than with coalition politics. Secondly, AKP first burst onto Turkey’s political scene against the backdrop of instability resulting from coalition governments unable to guide the country through economic difficulties. This lesson has been deeply ingrained on both the party’s psyche and, they hope, the country’s.

“The right choice is stability,” was one of AKP’s election slogans. It will likely be the basis for their strategy going forward. If Turkey can be shown to be ungovernable under the current distribution of votes, AKP’s leadership might calculate that they will be able to make a strong case to the swing voters who deserted the party that they are better off returning to the fold. With political uncertainty almost certain to fuel further economic softening, AKP might gamble that if it assembles a passive, minority government, the situation in Turkey will deteriorate to the point that, in a couple of months, it can call a new election, point to the negative consequences of dispersed power, and be returned to a solid majority.

Already, the outlines of such a campaign are evident. The day after the election the pro-government Daily Sabah ran a page-long interview with an Italian expert praising that country’s law banning coalition governments as the best recipe for stability for successful governance. Turkey’s economy is already showing strain. The lira, which had fallen steadily ahead of the election, hit a record low in response to the AKP’s lost majority, and stocks on the Istanbul Stock Exchange dropped sharply on Monday morning.

Davuto?lu, in AKP’s balcony speech, continued the party’s pledge of stability. “No one should worry,” he assured. “We will take every precaution within this political framework to maintain stability and the comfort that [AKP has] provided in the last 12-13 years.” If Erdo?an’s presidential system was a step too far for Turkey’s voters, maybe such a promise of stability will prove a more palatable proposition in the next go around.

The Endless Campaign

If such will indeed be the AKP’s strategy, Turkey appears destined for a state that is familiar to the American public: endless campaigning.

In such an environment, the opposition parties will face a major challenge and none more so than HDP. Unless it joins a coalition, it will be unable to pursue its agenda. And a minority AKP government will be unlikely to pursue its peace opening to the Kurds, choosing, if anything, to trend more nationalist to win back voters from MHP. Further, should there be another election shortly, HDP might struggle to hold onto the protest voters, especially if it appears that their votes, despite weakening AKP, did not deliver any significant change to the makeup and direction of the government. Demirta? would have to walk a fine line between persuading Kurds that he can deliver a solution through the political process and moving towards a more national party with a broader agenda to keep the support of the Turks that also cast their ballots for him.

At the same time, MHP will have to fight to hold onto its nationalist voters, especially those that might buy into AKP’s argument that protecting the state will require returning to single party rule. Their natural inclination will be to warn of the danger for the Turkish state represented by the HDP’s stunning success. CHP, too, will have to make a convincing case of why it deserves continued support after a disappointing finish. Internecine conflict between K?l?çdaro?lu’s reform-minded wing and the staunch, Kemalist old-guard he sidelined is likely. CHP insiders are already murmuring that Deniz Baykal, the scandal-ridden former leader of the party, might be preparing a comeback.

Amid this uncertainty and likely recurring political contest, the next couple of months in Turkey will be shaped by how the parties and voters confront these challenges. If the same voting blocs and priorities can be maintained for the foreseeable future, AKP might be even further weakened should another election be held. But alarm in the face of rising instability?whether real or manufactured?might persuade those Turks who had abandoned AKP that too much stability is the lesser of two evils, after all.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now