Immigration and the Labor Force

The 2016 presidential campaign has brought immigration back into the spotlight, with candidates crafting messages and policies to address this important issue?particularly as it relates to job creation. In particular, there has been a growing narrative that high levels of immigration have led to declining employment and labor force participation among the native-born population. This has led some to advocate for a more restrictive federal immigration policy.

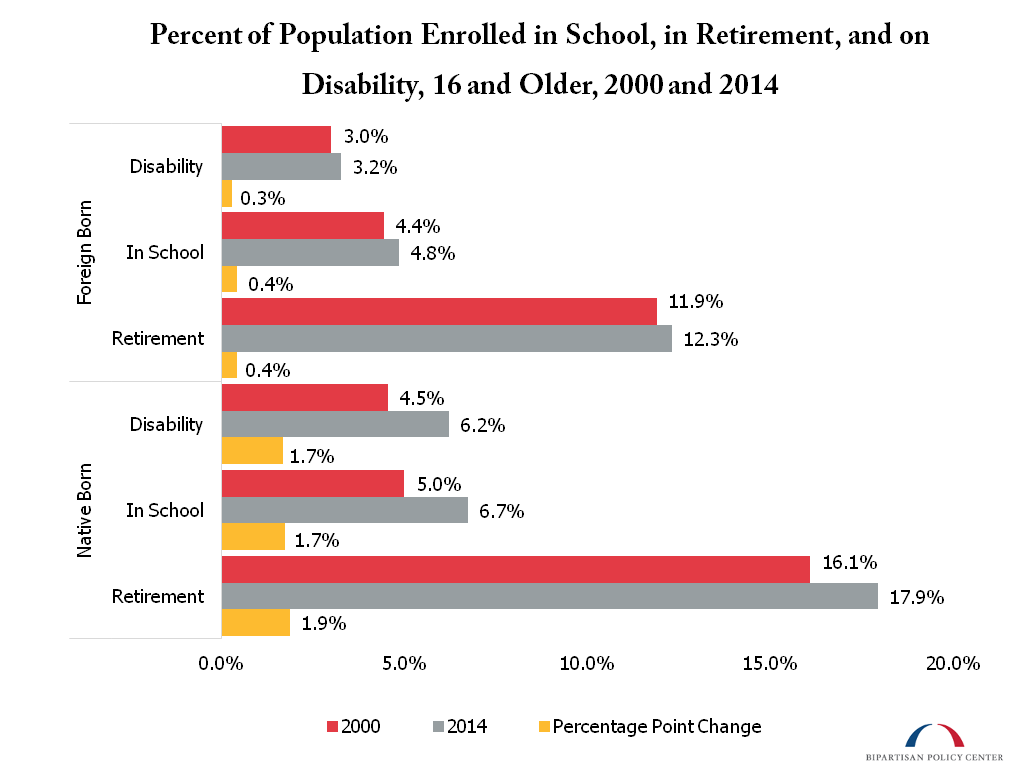

Though compelling, this argument is overly simplistic and ultimately flawed, as it fails to consider the many factors that influence labor force participation besides immigration. Native-born Americans are far more likely to exit the workforce to enroll in school, retire or enter disability, and these factors have driven the decline in employment and labor force participation over the past 15 years?not immigration.1

Population and Labor Force Trends

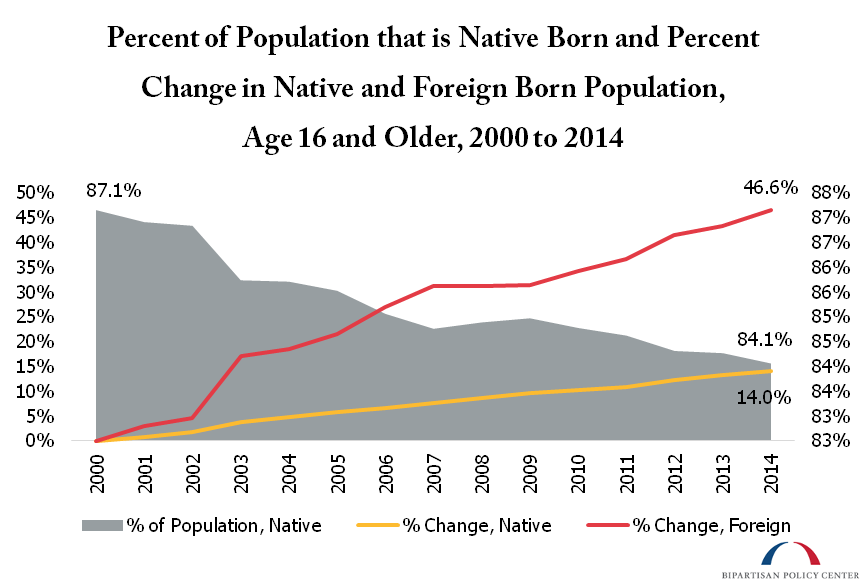

The foreign-born population in the United States has been growing at a far faster rate than the native-born population. While the native-born population is seven times larger than the foreign-born population, between 2000 and 2014 the number of foreign-born adults increased by almost 50 percent, compared to just a 14 percent increase for the native adult population. This caused the native-born share of the total adult population to decrease from around 87 percent to 84 percent.

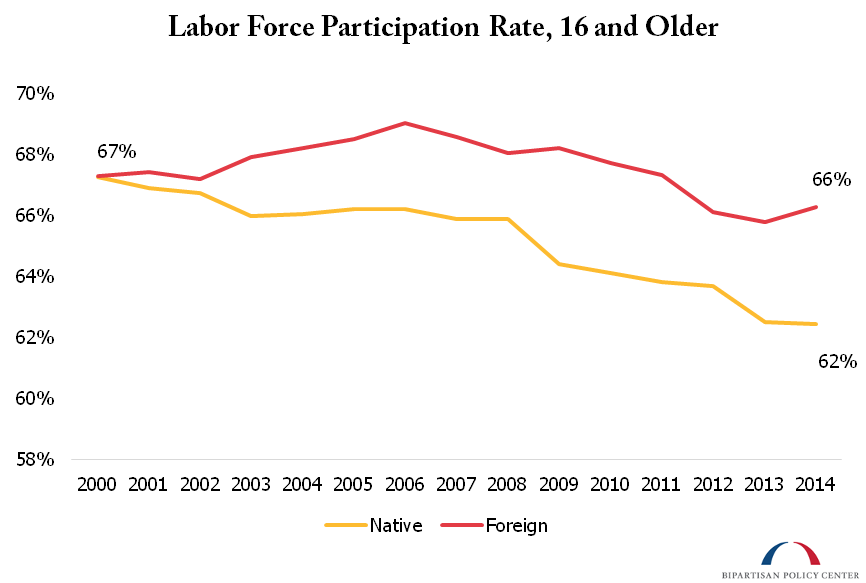

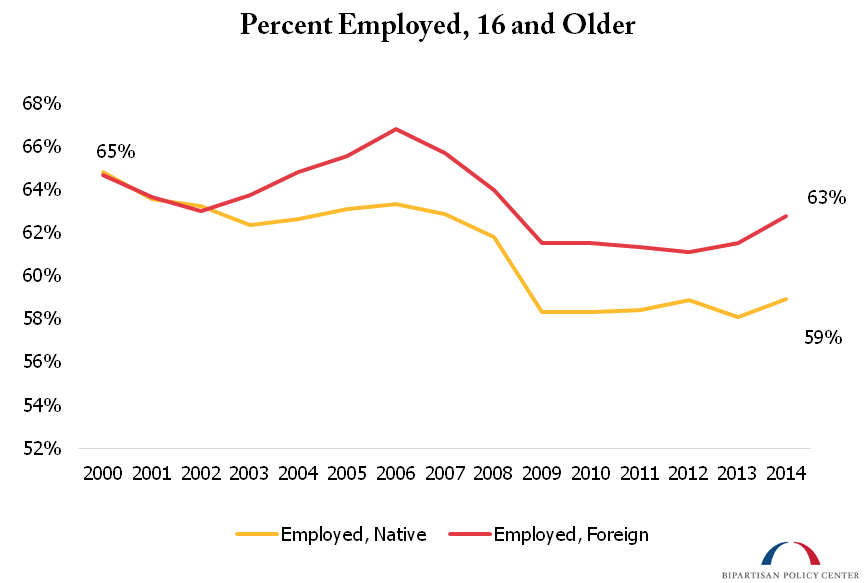

The labor force participation rate2 has also been on a downward trend among the native adult population. Between 2000 and 2014, native-born individuals realized a 5 percentage point drop in the labor force participation rate, from 67 to 62 percent, while the foreign-born labor force participation rate decreased by just 1 percentage point, from 67 to 66 percent. Similarly, the native-born employment rate3 declined by 6 percentage points over this period, from 65 percent to 59 percent. Among foreign-born individuals, employment dropped by just 2 percentage points, from 65 percent to 63 percent.

From the above charts, it is easy to sympathize with the belief that immigration has forced native-born Americans out of the labor market. Under this theory, a glut of foreign workers has decreased the number of available jobs; native-born individuals have suffered the brunt of this trend, plagued with declining levels of employment and labor force participation.

However, despite its superficial appeal, this conclusion is extremely problematic for two reasons:

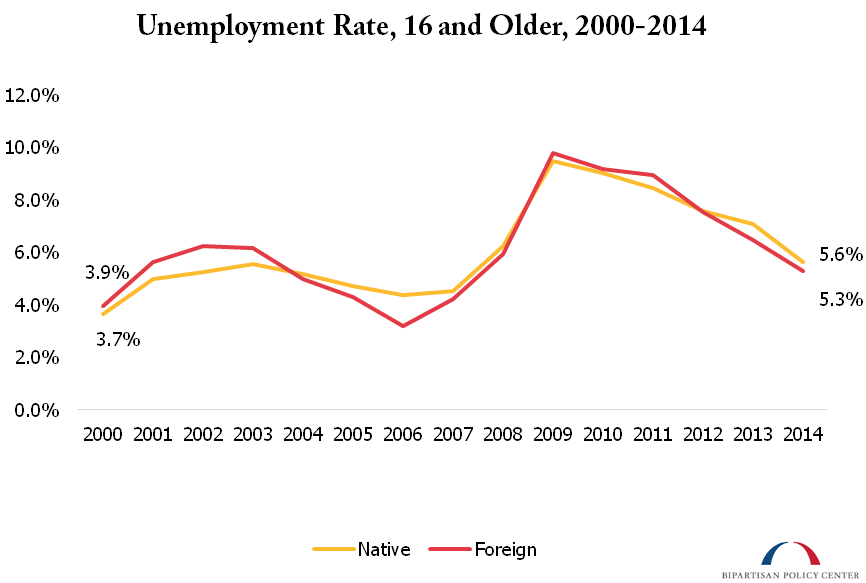

Unemployment Rate Parity. The past several years have seen almost no divergence in foreign- and native-born unemployment rates;4 the two have remained almost identical since 2000, varying by no more than a few tenths of a percentage point. In 2000, native-born unemployment stood at 3.7 percent, compared to 3.9 percent for foreign-born. By 2014, native-born unemployment had increased to 5.6 percent, compared to 5.3 percent for foreign-born. If immigration were the root cause of declining native-born employment, one would certainly expect the foreign-born population to have a significantly lower unemployment rate than native-born.

Lump of Labor Fallacy. Blaming immigration for declining employment ultimately rests on the flawed belief that economies can only produce a fixed number of jobs and that for every job occupied by an immigrant, a native-born worker must be unemployed. Known as the “lump of labor fallacy,” this assumption has been discredited by a large body of economic research. In fact, textbook economics indicates that immigration can actually spur job creation, as population growth boosts aggregate demand, leading to economic growth and employment opportunities. According to Adam Looney of the Brookings Institution, “Immigrants and U.S.-born workers generally do not compete for the same jobs; instead, many immigrants complement the work of U.S. employees and increase their productivity.” A paper by Harry Holzer of Georgetown University echoes this belief, and a study from the San Francisco Federal Reserve Board found no evidence that immigrants displace U.S. workers.

This evidence ultimately calls into question the notion that immigration is the driving force behind declining native-born employment and labor force participation. Rather, these trends can be largely attributed to individual labor market decisions. Specifically, native-born individuals are far more likely to exit the workforce to enroll in school, retire, or enter disability. Indeed, between 2000 and 2014, both disability and school enrollment increased by 1.7 percentage points among the native-born population, while retirement rose by 1.9 percentage points. Meanwhile, these factors barely budged for the foreign-born population?rising by less than a half of a percentage point for each.

At the heart of these trends lies the fact that native-born individuals generally have a greater amount of options than the foreign-born population with regard to their labor market decisions. Immigrant families have lower median incomes, and are more likely to be living below the poverty line?thus they are less likely to have the means to enroll in college. Immigrants also tend to have lower levels of retirement savings. And undocumented immigrants?which comprise around 28 percent of the foreign born population?are unable to qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance. As such, native-born adults have far more flexibility to exit the workforce in favor of retirement, schooling or disability, which puts downward pressure on native employment and labor force participation, regardless of the presence of immigrants.

Contrary to campaign rhetoric, there is no clear evidence that immigration has brought forth a decline in native-born employment or labor force participation. There has been very little divergence in the native born and foreign born unemployment rates, and a breadth of research indicates that immigration can be complementary to native born employment, as it spurs demand for goods and services. What is ultimately behind the downward trend is the fact that native-born Americans are more likely to have the option to exit the labor market?to attend school, enter retirement, or collect disability insurance. The immigrant population often lacks this flexibility, which has led to higher labor force participation among the foreign-born population.

1 This blog uses data from the US Census Bureau’s October Current Population Survey from 2000 to 2014. The October Supplement is when the CPS surveys education enrollment. All data is for the population age 16 to 90.

2 Defined as the percentage of the population that is either employed or actively seeking work.

3 Defined as the percent of the adult population (age 16 and older) that is employed.

4 The unemployment rate is the percentage of individuals who do not hold a job?but are actively seeking one.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.