H-1B Visa Cap Expected to Be Hit Within Days—Again

UPDATE – April 7

The #H1B cap for FY2015 has been reached: http://t.co/JzKuUtk4sD #CIR #immigration

? Matt Graham (@Matt__Graham) April 7, 2014

For the second year in row, employers are expected to file enough H-1B visa petitions to reach the annual limit within days after the filing window opens. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) opened the filing period for FY 2015 visas today and has already announced that it anticipates receiving more than enough petitions to reach the cap by April 7. For approved petitions, visas will be available on October 1, 2014, the beginning of the fiscal year. Each year’s application period usually opens on April 1st?six months prior to the beginning of the fiscal year. Typically, the earliest an employer may petition for an H-1B visa is six months prior to the “need” for a foreign worker. However, because caps are met quickly each year, employers rush to apply by April regardless of actual need.

The H-1B Specialty Occupations visa is one of several temporary categories that authorize “non-immigrants” (i.e., those who are not granted permanent residence or a green card) to work in the United States. The program was created in 1990 and allows U.S. employers to temporarily employ foreign skilled workers in “specialty occupations” that require expertise in specialized fields and a bachelor’s degree or higher.1

- Period of stay. H-1B visas are issued for a three-year period and can be extended once for an additional three years.2

- Numerical limit. H-1B visas for initial employment are subject to an annual cap of 65,000 per year, plus an additional 20,000 visas set aside for foreign nationals with a U.S. master’s degree or higher.3 Certain employers, however, are exempt from the cap. Thus, the actual number of approved visas in a given year typically exceeds the cap of 85,000.4

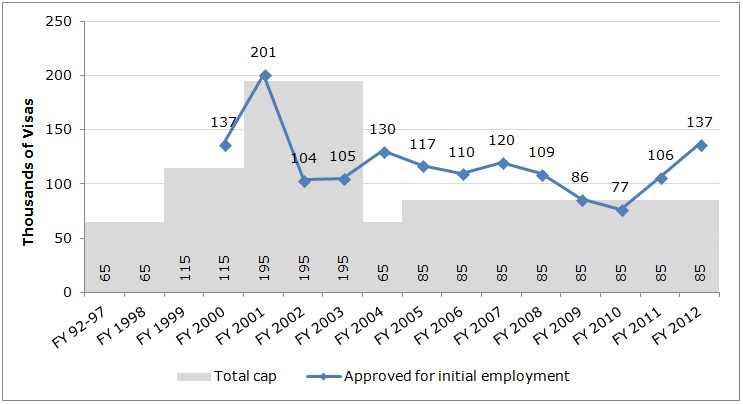

Figure 1: H-1B Cap and Petitions Approved for Initial Employment, FY 1992?FY 2012.

Source: USCIS, “H-1B Visa Characteristics,” compiled from FY 2012, FY 2011, FY 2008, FY 2005, FY 2004, and FY 2000 editions.

Note: Counts of approved petitions represent the year petitions were approved, regardless of when the application was filed.

The H-1B cap has fluctuated since the visa category was created in 1990 (Figure 1). Although the cap was rarely hit in the early 1990s, by the mid-1990s, the 65,000 cap was usually hit, prompting increases in the following years. The cap was first raised to 115,000 for FY 1999 and FY 2000 by the American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act of 1998. Two years later, the cap was raised to 195,000 for FY 2001 through FY 2003 by the American Competitiveness in the Twenty-first Century Act of 2000. In FY 2004, the cap reverted to 65,000. Finally, for FY 2005, the H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004 mandated that 20,000 additional visas be set aside for the master’s exception, bringing the total H-1B cap to 85,000.5

Demand for H-1B Visas

Demand for H-1B visas has exceeded the annual cap every year since 2004. Last year, USCIS announced that it had received a sufficient number of H-1B petitions to reach the cap for FY 2014 on April 5?five days after it began accepting petitions. This is not a new phenomenon. Although the pace at which employers filed petitions decreased during the recession, the H-1B cap was hit within two days for the FY 2008 filing year and within five days for FY 2009. It was reached within one month for the FY 2007 filing year. (See Table 1.)

When the FY 2008 cap was reached within two days in 2007, USCIS established a lottery selection process that randomly determined which H-1B petitions would be processed, since it was impossible to establish the order in which petitions were filed. The same process was used during last year’s five-day H-1B season when the number of H-1B petitions for FY 2014 reached 124,000. USCIS announced last week that it expects to use the lottery system once again this year to meet the numerical limit for FY 2015. While the process of randomly selecting petitions is understandable from the administrative perspective of USCIS, the process essentially determines the “winners and losers” of the H-1B visa year without regard to merit.

Table 1: Date H-1B Caps Reached, FY 2000-FY 2015.

| Year | Cap reached (65,000) | Master’s cap reached (20,000) | Total cap |

| FY2015 | 85,000 | ||

| FY2014 | April 5, 2013 | April 5, 2013 | 85,000 |

| FY2013 | June 11, 2012 | June 7, 2012 | 85,000 |

| FY2012 | November 22, 2011 | October 19, 2011 | 85,000 |

| FY2011 | January 26, 2011 | December 22, 2010 | 85,000 |

| FY2010 | December 21, 2009 | July 9, 2009 | 85,000 |

| FY2009 | April 5, 2008 | April 5, 2008 | 85,000 |

| FY2008 | April 2, 2007 | April 30, 2007 | 85,000 |

| FY2007 | May 26, 2006 | July 26, 2006 | 85,000 |

| FY2006 | August 10, 2005 | January 17, 2006 | 85,000 |

| FY2005 | October 1, 2004 | Not reported | 85,000 |

| FY2004 | February 17, 2004 | N/A | 65,000 |

| FY2003 | Not reached | N/A | 195,000 |

| FY2002 | Not reached | N/A | 195,000 |

| FY2001 | Not reached | N/A | 195,000 |

| FY2000 | July 21, 1999 | N/A | 115,000 |

Source: USCIS press releases, FY2011, FY2012, FY2013, FY2014, FY2015; GAO-11-26 (FY2000-FY2010).

Note: The master’s exemption was first introduced in FY 2005.

Current Legislative Proposals

The House and Senate each recently proposed reforms to the H-1B visa program. The Senate-passed Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 (S.744) would increase the base cap from 65,000 to a flexible cap of 115,000-180,000 based on economic circumstances and would increase the exemption for advanced degree holders from 20,000 to 25,000. The bill would also increase prevailing wage requirements for H-1B visa holders (from 95 percent of the prevailing wage to 100 percent) and mandate that employers advertise job openings to American workers for at least thirty days prior to hiring an H-1B worker. The House Judiciary Committee also approved a bill last year with H-1B reform proposals. H.R. 2131, the Supplying Knowledge-based Immigrants and Lifting Levels of STEM Visa Act (or SKILLS Visa Act) would more than double the base cap from 65,000 to 155,000 visas. The bill would also increase the exemption for advanced degree holders from 20,000 to 40,000 visas per year.

As the immigration reform debate continues through the spring and the House considers if and when it will address the issue, this latest announcement from USCIS will surely renew calls to more closely align the H-1B visa cap with employer demand.

Paul Stern contributed to this post.

1 Limited exceptions to the bachelor’s degree requirement are available for individuals who can demonstrate that they possess the equivalent skills or experience in their field. In FY 2012, 796 of the 136,890 petitions granted for initial employment were for individuals who possessed less than a bachelor’s degree (0.58 percent).

2 Although the H-1B visa allows a temporary stay, the law allows H-1B visa holders to be sponsored for permanent residence while in the United States in H-1B status. This is called “dual intent,” i.e., the individual holds both the intent to abide by the temporary nature of the H-1B status while in that status, and to immigrate when an immigrant petition is approved and an immigrant visa is available.

3 Once the initial 20,000 visas set aside for advanced degrees are used up, additional advanced-degree applicants count against the regular 65,000 cap.

4 Nonprofit organizations, government research organizations and institutions of higher education are exempt from these limits, and USCIS continues to accept petitions from cap-exempt employers after the cap has been reached. Thus, the actual number of approved H-1B visas in a given year typically exceeds the annual cap of 85,000. Petitions for continuing employment of previously-approved foreign nationals are also exempt from the cap. These include requests for extensions of stay, amended petitions, transfers to new employers or concurrent employment in a second H-1B position.

5 USCIS, “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers,” available at: http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/H-1B/h1b-fy-12-characteristics.pdf.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.