The Earned Income Tax Credit: Facts, Statistics and Context

By Shai Akabas and Matt Graham

Brian Collins, Kristen Masley, and Holt Dwyer contributed to this post.

The purpose of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is to reduce federal income and payroll taxes for workers with low to moderate incomes. The credit is particularly supportive to low-income workers because it is refundable; even if the credit’s dollar amount exceeds a worker’s income tax liability, the balance is still paid to the worker through the tax refund process. In this manner, the credit can offset or even exceed federal income and payroll taxes owed.

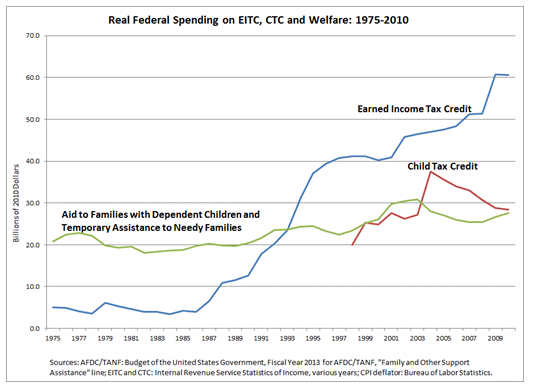

The EITC has been expanded several times since its creation in 1975, and more than half of the states and the District of Columbia now have their own supplemental EITCs. The credit was originally envisioned as a way to combine the anti-poverty effects of proposed negative income taxes (which were criticized as undermining work effort) with an incentive for employment for low-income Americans with children, thus combining policy priorities of both Democrats and Republicans.

The maximum credit nearly doubled as part of a 1986 tax reform package that received broad bipartisan support and was hailed by President Reagan as “the best antipoverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress.” In 1993, however, the major expansion that was pushed for and enacted by President Clinton came without Republican support. A further change was adopted shortly thereafter to expand the program to the childless working poor.* Some viewed this as an ill-conceived expansion beyond the credit’s original intent. Much of the current opposition and criticism stems from the program’s expanding scope and costs ? since the 1986 expansion, real costs of the program have grown by a factor of ten, and almost one in five taxpayers now claims the credit.

Source: Tax Policy Center

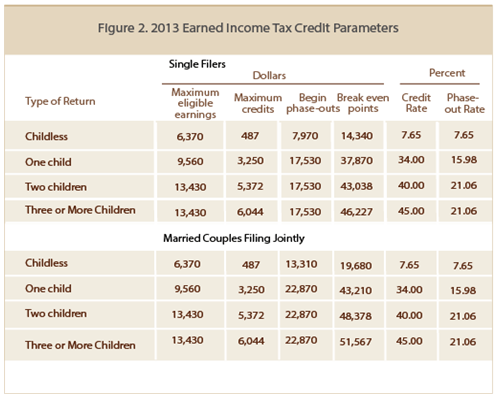

Although it is open to any low- or moderate-income worker who meets its qualifications, the EITC is largely designed to help families with children, with benefit levels increasing for each of the first three children in a household. Thus, in 2013, the maximum credit for a childless adult is $487, while the maximum credit for an adult with three children is $6,044. For tax year 2011, the most recent year for which data are available, over 27 million people received nearly $62 billion from the EITC, an average of just over $2,300 per person.

By tying the value of the credit to the amount of income earned from work, the EITC strengthens incentives for individuals who are not working, including those on welfare, to seek employment, and for low-wage workers to seek an increase in work hours.

In recent weeks, the EITC has entered the immigration debate. Newly legalized immigrants and expanded legal immigration could substantially increase the number of workers eligible for the credit, depending on congressional action, thereby increasing program costs. By way of comparison, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 (which contained similar provisions to S.744, the Senate’s current draft immigration bill), was expected to increase spending on refundable tax credits such as the EITC by $13.7 billion over a decade.** Therefore, EITC eligibility is an important issue in the immigration debate.

Who is eligible for the EITC?

The process of determining who is eligible for the EITC is complicated, and involves more than 20 separate criteria. However, there are four main qualifications. First, an individual must have a Social Security number that is valid for employment. Second, an individual must have earned income either from working for someone else or from owning or operating a business or farm. Third, an individual must be a U.S. citizen or resident alien for the entire applicable tax year, or the spouse of a citizen or resident alien. Finally, earned income and adjusted gross income must both be below income limits that vary by the number of children in a family, and the filer must have investment income of no more than $3,300 per year.

The amended Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S.744) would assign legalized immigrants Social Security numbers as soon as they gain registered provisional immigrant (RPI) status, the bill’s precursor to awarding legal permanent residency (a green card). Therefore, it seems likely that legalized immigrants who meet the other requirements would be eligible for the EITC if S.744 becomes law. Although the Senate bill denies “any Federal means tested public benefit” (as defined in 8 U.S.C. 1613) to immigrants in RPI status, current federal regulations interpreting that clause do not include the EITC among prohibited benefits.

How is the amount of the credit calculated?

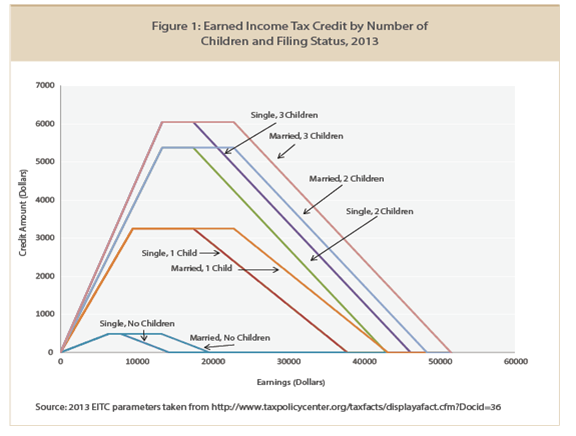

The value of the credit is calculated based on the amount of income earned, as well as the individual’s or couple’s marital status and number of qualifying children. At very low income levels, the credit is a proportion of the filer’s earned income, with that proportion (the “credit rate”) determined by the number of dependent children. The credit plateaus at a certain level, remaining fixed as income increases. If income continues to grow beyond a certain level, the credit is reduced by a constant share (the “phase-out rate”) of the additional income until the support is completely phased out. The phase-out rates are also determined by the recipient’s number of qualifying children.

Source: Tax Policy Center

Take, for example, a single filer with two children in 2013. Between the income levels of $0 and $13,430, the individual’s credit increases by 40 cents for each additional dollar of income. Between the income levels of $13,430 and $17,530, the individual’s credit plateaus at the maximum credit level of $5,372. If the individual’s income exceeds $17,530 (this is the phase-out level), his/her credit is phased-out at a rate of 21.06 cents for every additional dollar of income (an additional “hidden” marginal tax rate of 21 percent). The individual’s credit continues to be reduced until an income level of $43,038 is attained (the “break even point”), at which point the credit is zero.

The process is similar for married joint filers except that the plateau range is extended by approximately $5,000, meaning that the filer above, if married, would not enter the phase-out until joint income reached $22,870. Whether single or married, a filer with more children will have a larger maximum credit, but beyond three children, the credit stops increasing. A table from the Tax Policy Center spells out the details:

Source: Tax Policy Center

Disadvantages of the current EITC

One negative quality of the EITC is its complexity. This complexity causes problems for filers as well as additional government bureaucracy. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates that one in five eligible people do not seek EITC benefits. In addition, many low-income people who claim the EITC are required to spend money on tax preparers in order to ensure that they have properly claimed the credit.

The EITC also has high rates of improper payments?some due to honest mistakes, others as a result of fraud?that continue to be a problem. In tax year 2012, for instance, the IRS estimates that almost 23 percent of paid benefits were improperly claimed.

Lastly, while the EITC increases incentives for work over the income range in which the credit grows, some argue that the phase-out could discourage additional work because its phase-out rate functions as a “hidden” marginal tax rate increase on people whose incomes fall in that range. Empirical evidence, however, generally suggests that the EITC may not reduce work hours and may have increased labor force participation among single mothers (Eissa et al. 1996; Meyer 2002; Meade et al. 2001). This may be partially due to policies such as the Child Tax Credit, which somewhat lessen the phase-out’s impact.

Conclusion

As Congress continues debating reforms to our complex immigration system, entitlement programs and benefits, as well as our inefficient tax code, will continue to play an important role in the conversation. The EITC is a key part of this conversation as it pertains to our nation’s economic growth and the structure of our future immigration system.

* Additionally, the EITC was further expanded in 2009 to add an additional tier for families with three or more children and reduce the credit’s marriage penalty.

** The comparable figure today would be somewhat higher, due to wage growth, population growth, and the expansions enacted in 2009.

References

Cordes, Joseph J., Robert D. Ebel, and Jane G. Gravelle, ed. NTA Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute Press, 2005. s.v. “Earned income tax credit.” http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxtopics/encyclopedia/EITC.cfm (accessed May 30, 2013).

Eissa, Nada, and Jeffrey Liebman. “Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. (1996): pp. 605-637.

Maag, Elaine and Adam Carasso. Tax Policy Center: Urban Institute and Brookings Institute, “Taxation and the Family: What is the Earned Income Tax Credit?.” Last modified January 12, 2013. Accessed May 30, 2013. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/key-elements/family/eitc.cfm.

Meyer, Bruce D. and Dan T. Rosenbaum. “Welfare, The Earned Income Tax Credit, And The Labor Supply Of Single Mothers,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2001, v116 (3 Aug), 1063-1114

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Last modified February 1, 2013. Accessed May 30, 2013. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=2505.

Meade, Erica, and James P. Ziliak, Ph.D. University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, ” A State Earned Income Tax Credit: Issues and Options for Kentucky.” Last modified 2007. Policy Insights: Occasional policy brief #2Accessed May 30, 2013. http://www.ukcpr.org/Publications/PolicyInsights3.pdf

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now