Crude Oil Swaps with Mexico and the Crude Oil Export Ban

On August 14, several outlets reported that the Obama administration would allow U.S. energy companies to send crude oil to Mexico as part of a swap transaction in return for Mexican crude. After Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, called into question last week whether any of these deals have actually been approved, an increasing level of scrutiny is falling on crude swaps and their potential impacts. Specific interest is growing in how the swap deal affects prospects for the hotly contested crude oil export ban.

Crude oil exports are currently prohibited by law following legislation passed in the wake of the 1973 Arab oil embargo. Discussions surrounding lifting the crude oil export ban are gaining traction in Congress, as both the House and the Senate have recently moved legislation lifting the ban, despite a veto threat from President Obama. At this point, it’s unclear what impact the administration’s decision to allow swaps may have on the ultimate fate of the crude oil export ban. However, the apparent logic behind the move recognizes that domestic crude production and refinery configurations are mismatched.

As a result of market conditions and activities that preceded the growth of domestic unconventional shale development, many U.S. petroleum refineries are designed to process the heavier crudes that we have typically imported. Mexico generally produces this heavier crude, an ideal match for Gulf coast refineries. Meanwhile, the United States now produces mostly light crude oil, which is ideal for the configuration of Mexican refineries, allowing them to run more efficiently. The swap decision provides American producers with another destination for their supplies, meaning the administration’s decision will alleviate some of the bottleneck created by the mismatch of U.S. oil and its refineries. This deal has the potential to increase U.S. production, which has declined over the last few months as producers have been forced to cut production in the face of sustained low oil prices.

Oil swaps?

It is important to note that the ruling is limited to swap transactions, meaning the volumes sent into Mexico must be reciprocated via exports to the United States in roughly equivalent amounts. The United States has been able to export crude oil to Canada since 1985, as long as it is consumed (refined) in Canada. Similarly, the swapped U.S. crude must be refined in Mexico. Sen. Murkowski has also inquired about the Department of Commerce’s process for approving crude exports to Canada, highlighting that swap deals and exchanges may be the next front in the crude oil export fight. The U.S. Energy Information Administration noted that:

Crude swaps are provided for in longstanding regulations governing crude oil export controls. However, no licenses for swaps had been granted until [Bureau of Industry and Security] BIS’s August 14 announcement of swaps with Mexico.

Some key elements on swap deals include:

- Swap deals are authorized by the Bureau of Industry and Security, located within the Department of Commerce.

- All deals must be found to be in the “national interest”, although the criteria are less stringent than for crude oil exchanges and can be approved based on “convenience and increased efficiency of transportation”.

- There are two different types of swaps, for adjacent countries and non-adjacent countries. Canada and now Mexico are the only two countries where swaps have been authorized, both under the adjacent categorization. It’s worth noting that Panama would also qualify as an adjacent country, although there’s no indication that a swap deal with Panama has even been discussed thus far.

- No swaps have been approved for non-adjacent countries.

- The swap contracts must contain a provision that allows for termination in the case of an oil shortage.

- Swap deals are also subject to the requirement that they do not “diminish the total quantity or quality of petroleum available to the Unites States”. In other words, they must be of equal or greater quality and quantity.

- The characteristics of Mexican refineries could mean that the swap deal would provide environmental benefits by freeing up sulfur-removing capacity, thereby producing more low-sulfur gasoline than is currently possible.

- Additionally, little is known of the quantity of the contracts that will be approved, beyond the potentially 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) involved in the deal with Pemex, Mexico’s state oil company.

For more information on BIS swap criteria, see here.

What does this deal mean for U.S. oil exports?

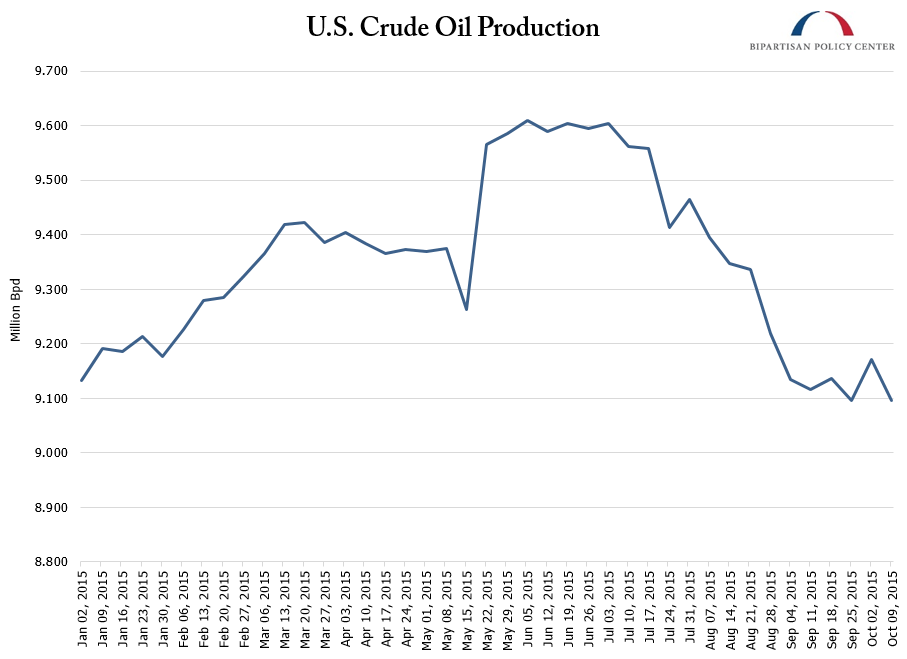

With the export ban still in place, and only limited amounts of exports allowed through swaps, one could contend that this announcement is simply a continuation of current policy rather than any radical break from it. The decision shows some degree of flexibility within the current regulatory structure, however, the actual volumes cleared for swap deals may not turn out to be significant. Given that the known volumes represent a tiny fraction of the over 9 million bpd that the United States is currently producing, it appears as though the potential deals might not have any industry-shifting impact in the immediate future.

The potential agreement might be better interpreted as simply the next step in an ongoing effort to enhance the American energy security relationship with Mexico. For example, Congress passed the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Hydrocarbons Agreement in December 2013 in hopes of promoting cooperation over oil and gas developments in part of the Gulf of Mexico. Efforts to enhance oil and gas infrastructure (for example, pipelines) between the countries are continuing, such as when the House passed the Natural Gas Pipeline Permitting Reform Act in January 2015. Mexico’s oil and gas sector is also undergoing a transition, with the government auctioning offshore leases and opening the sector up for more private investment. Given the importance of the country for American energy security (Mexico was the third largest exporter of crude oil to the United States in 2014), potential swap agreements will strengthen the U.S.-Mexico energy relationship.

It’s too early to consider the swap deal as a change of heart from the Obama administration on the broader contours of the crude oil export ban, evidenced by the aforementioned veto threat. Moreover, ongoing conversations surrounding a possible trade for extended renewable energy tax credits as a way to garner increased Democratic support for lifting the ban make it difficult to discern such a sea change in the administration’s stated position. Separately, the lifting of sanctions as part of Iran nuclear deal does add an additional political dimension to the discussion as it could allow as much as an additional 1.1 million bpd onto the global market. This has many asking why U.S. producers aren’t able to export their product in the same way the Iranians would be able to. In the broader context, it appears that politics will drive any decision on ending the crude oil export ban.

However, the administration could begin approving non-adjacent country swap deals as a means to alleviate some of the ongoing supply glut by better aligning refining configurations and supplies. While approving non-adjacent swaps could be indicative of a more significant policy shift and therefore more politically challenging, the administration has already approved the export of condensate, an ultralight form of crude oil, based on distillation practices within current regulations. The swap deal with Mexico demonstrates that the administration has a grasp on the compelling need to relieve some of the downward pressure on oil production?although this move shouldn’t be considered a substitute for ending the crude oil export ban.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give NowRelated Articles

Join Our Mailing List

BPC drives principled and politically viable policy solutions through the power of rigorous analysis, painstaking negotiation, and aggressive advocacy.