Acceleration in Suspicious Activity Reporting Warrants Another Look

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) was originally enacted in 1970 to restrict money laundering by organized criminals and tax evaders. Since 1970, the structure and usage of the BSA were repeatedly changed and expanded, as noted in a previous Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) post. This analysis looks at the impact of the increasing scope of anti-money laundering laws.

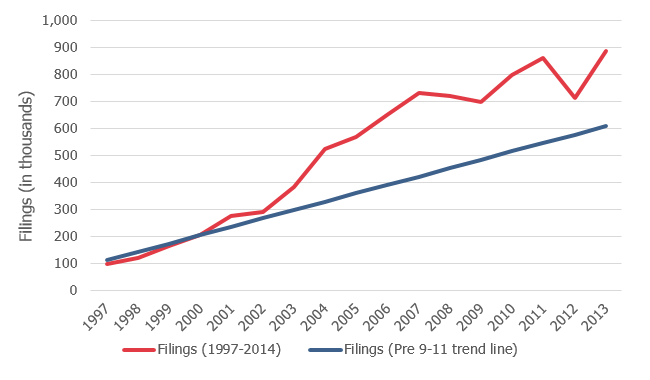

BPC’s Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative set out to find empirical evidence of anti-money laundering (AML) expansion. The data shows a 55 percent increase in the number of Suspicious Activity Reports (SAR) filings after the USA PATRIOT Act (Patriot Act) was passed from the pre-2001 trend. This suggests that something has indeed changed the reporting mindset of institutions subject to the BSA. It also raises some questions: what are these additional reports being used for? Do regulators have the resources necessary to handle the increased flow of information? Are resources being used as efficiently as possible to catch the most important targets of illegal activity?

Here’s what we found:

FinCEN Reports

SARs are an integral part of the U.S. anti-money laundering regime. The BSA effectively deputizes financial institutions to monitor and report suspicious activity under the theory that financial institutions are in the best position to detect illegal use of the financial system. This policy is implemented through the BSA’s customer due diligence rules which require banks to have policies and procedures in place to evaluate and report suspicious activity.

The U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) regulations require banks to report suspicious activity when they suspect or have reason to suspect a transaction involved illegally derived funds or funds involving an illegal purpose. Activities likely to trigger a SAR include the obvious such as detected money laundering and transfers to terrorist organizations, but also less obvious transactions such as those structured in ways that appear designed to evade BSA reporting and those abnormal for a particular customer without a reasonable explanation. Banks and other financial institutions examine billions of transactions, including ones made on credit or debit cards, to try to determine whether to file a SAR.

In contrast to the SAR, the BSA’s Currency Transaction Reports (CTR) simply involve any cash or check transaction at or above $10,000, regardless of suspicion. Because the CTR threshold is not indexed to inflation, the number of CTRs filed has increased dramatically as the value of $10,000 has decreased ($10,000 in 1970 adjusted for inflation is over $60,000 today). Therefore, activities like small businesses depositing cash on a regular basis are much more likely to trigger a CTR today than in 1970.

Suspicious Activity Report Data

FinCEN releases BSA reporting data quarterly by filing type and institution type. We focused solely on depository institution SAR filings because banks have had the longest and most consistent filing requirements. We did not consider CTRs because they are automatic, not indexed to inflation and do not require a suspicion determination on the part of the reporting institution.

Using linear regressions of annual SAR filings from 1996-2014, we found a steep acceleration in the number of filings after the passage of the Patriot Act in 2001. It is important to note that the Patriot Act did not directly expand the scope of activities for which banks were required to file SARS. It did enhance the number of entities which had to file. Our data analysis looked only at bank filings as they were subject to reporting prior to the Patriot Act. We estimated that there would have been around 600,000 bank SAR filings in 2014 had the increase followed the pre-2001 trend line. In fact, the actual number was 927,000. This 55 percent rise indicates that banks significantly increased their filings after the Patriot Act, a trend that remains to this day.

Note: The red line represents the number of filings between 1997 and 2014. The blue line represents the pre-9/11 trend line.

The data alone does not explain what is causing the acceleration. As the legal requirement for banks to file SARs did not change, there must be another driver. Juan Zarate, a former deputy national security advisor and current senior advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, suggested in his book, Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare, that the acceleration in filings was due to concerns by financial institutions about reputational risk stating that after 9/11, reputational risk became a “central part of a bank’s calculus.” Other possible explanations include regulators more vigorously pursuing BSA violations, a natural growth in reportable transactions or banks erring on the side of reporting versus not reporting.

Regardless of the explanation, the acceleration in SAR filings after 2001 raises several questions. First, is this reporting system the most efficient and effective possible? Second, does the current AML regulatory framework reflect the technological changes of the past few decades and the changing nature of finance? Finally, what are the unintended consequences of increased SAR reporting? Addressing these questions and others could lead to a rethink of the current AML regime, producing a more efficient and modern regulatory framework.

Share

Read Next

Support Research Like This

With your support, BPC can continue to fund important research like this by combining the best ideas from both parties to promote health, security, and opportunity for all Americans.

Give Now